|

|

St. Francis Dam Disaster

Excerpt (Chapter 19) from "Fifty Years a Rancher"

By Charles C. Teague

| Second Edition 1944

|

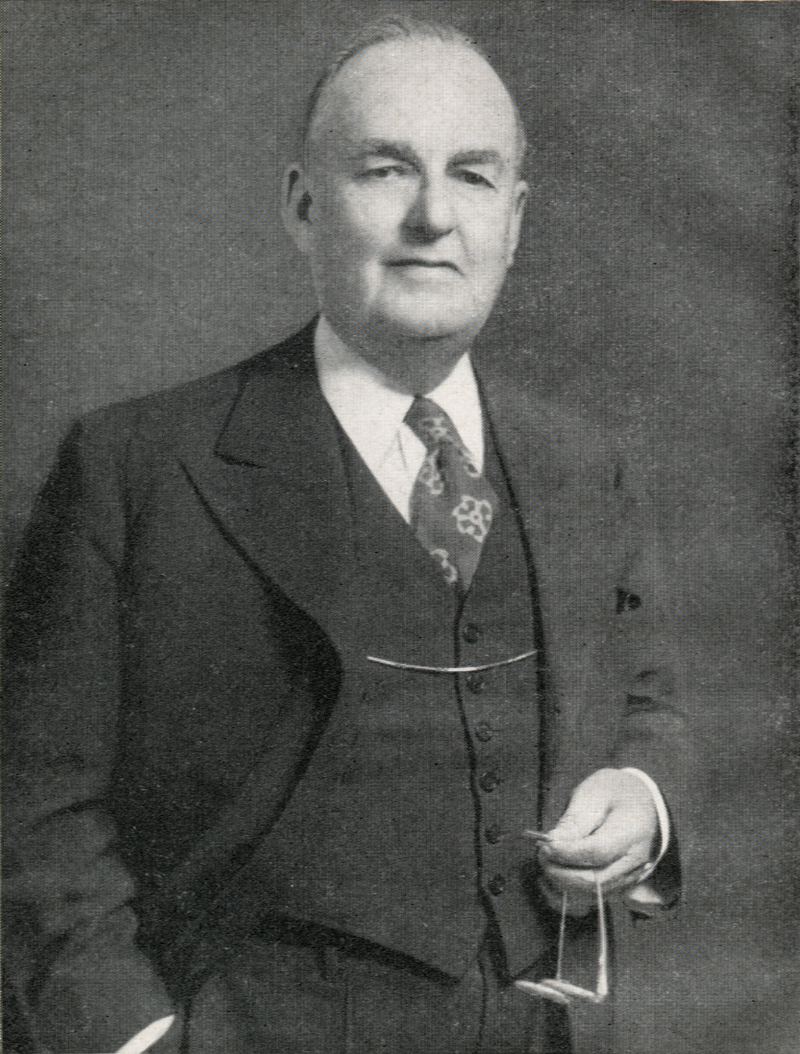

Charles Collins Teague (June 11, 1873 - March 20, 1950) came to Santa Paula as a young man in 1893 and soon took over the management of the Limoneira Co., which had been co-founded by pioneering California citriculturist Nathan Weston Blanchard and Teague's great uncle, Wallace Hardison of Union Oil fame. Teague, whose formal schooling ended at 17, revolutionized the business both scientifically and organizationally. He hired university scholars to develop new growing techniques that turned Limoneira into a major producer of oranges and walnuts; and he convinced other growers to band together to form the California Fruit Growers Exchange, a co-op better known as Sunkist. This enabled growers to time the market for the benefit of all, rather than allowing wholesale buyers to dictate the terms of individual transactions. Teague was Sunkist's longtime president. His prominence and organizational skills made him a natural to represent Ventura County farmers' interests in the wake of the 1928 St. Francis Dam disaster. He was appointed chairman of a county committee whose function was to assess damage and pursue restitution from the city of Los Angeles. In the text below, Teague emphasizes that all Ventura County claims were settled "without recourse to court action." The same could not necessarily be said of claims and claimants across the county line, which came under a separate committee. Perhaps ironically, Teague is remembered as the leader of the fight to stop the St. Francis Dam in the first place, on grounds it reduced Ventura County's water supply. As reported in the New York Times (3-15-1928), Teague had alleged that "Los Angeles, by means of the structure, was usurping the water rights of the valley by diverting the flow of the Santa Clara River. Legal suits to test the disputed points are still in the courts." (We haven't seen the lawsuits; perhaps the contention was that the dam impeded the flow of San Francisquito Creek, which drains into the Santa Clara.) RECENTLY I gave to the Huntington Library the manuscript of the "History of the St. Francis Dam Disaster" by George B. Travis. I attached to this manuscript the following foreword: "While fishing on the upper reaches of the Owens River I met for the first time Dr. Robert G. Cleland, who has contributed so much to posterity in the valuable histories that he has written of the early days of California. He has inspired me to furnish him for the Huntington Library certain manuscripts that I have, together with statement of my recollections of the last 50 years of the remarkable development and evolution of the walnut and citrus industries of California and the cooperative marketing organizations connected with those industries. "I happen to have in my possession the only authentic history of the St. Francis Dam Disaster, which was prepared by Mr. George B. Travis. "In 1929 I was drafted by President Hoover as a member of the Federal Farm Board, in which capacity I served for two years. While I was in Washington Mr. Travis, my former secretary, who was also secretary of the Joint Restoration and Rehabilitation Committee of Los Angeles and Ventura counties and who remained in California when I left, decided to write a history of the St. Francis Dam Disaster and the work of rehabilitation and restoration. Mr. Travis later became assistant to the secretary of the Farm Board. The first knowledge I had that Mr. Travis was engaged in writing this history was when he sent me the manuscript in Washington in 1929. In looking over the documents which I had in my possession I reread this manuscript. In retrospect, after the lapse of 15 years, the work of the public-spirited citizens who participated in the rehabilitation and restoration seems even more remarkable than it appeared at the time. The cost of rehabilitation and restoration to the City of Los Angeles was over 15 million dollars. Never before in the history of the world, so far as I am able to learn, was complete and equitable restoration and rehabilitation made by a great metropolitan people to a rural people, where damage had been done and where large sums of money were involved, without recourse to court action. In fact these settlements were made on the broad ground of moral responsibility without the legal responsibility having been previously determined by the courts. "In these days when there is so much evidence of strong governments taking advantage of the weak, and when many are becoming skeptical as to right and justice ultimately prevailing, the restoration stands out as a really great accomplishment. I am, therefore, presenting this document, together with a group of photographs, which tell, in pictorial form, the story. It is my hope that this settlement may serve as a precedent for the settlement of complex questions which arise in the future between persons and government and may restore in the minds of those who care to read it some of their lost faith in the justice of humanity." The following are my recollections of that disaster: On March 12, 1928, at 11:58 P.M. a disaster of huge proportions visited the Santa Clara Valley of the South. The tragedy was caused by the collapse of the St. Francis Dam, erected by the City of Los Angeles for the generating of hydroelectric power. The dam was 600 feet long and 180 feet high; it impounded about 38,000 acre-feet of water. The structure gave way so suddenly that the entire volume of water was at once released and swept through the Santa Clara Valley to the sea, a course of about 65 miles. For some distance below the dam the wall of water was at least 60 feet high and even when the flood reached Santa Paula, 50 miles below the dam, the crest was 25 feet above the normal level of the stream. The flood carried before it a terrific mass of debris trees, telegraph poles, bridges, railway tracks, fences, buildings in fact anything and everything movable that lay in its path. Three hundred and eighty-five lives were lost; 1240 homes were either completely destroyed or badly damaged; 7900 acres of land were flooded, and damage of every kind and degree was done to farms and orchards. The first problem presented by the disaster was naturally that of providing relief for the homeless and recovering the bodies of the dead. To meet the emergency a County Committee was set up, of which I was chairman. Subcommittees were appointed to obtain temporary housing, clothing, food and medical assistance. All citizens appointed on these committees met their responsibilities to the full, and worked heroically day and night until the critical phase of the emergency was over. We soon realized that the disaster was so great that we could not deal with it locally but would have to call for outside assistance. The situation clearly came under the province of the National Red Cross, and we called upon that body to come in and take charge. This it did. When the Red Cross representatives arrived, they said the emergency phases of relief in connection with the disaster were better organized than any they had ever known. The Red Cross officials at once declared that a public appeal should be made for funds. Before this could be done, however, Mr. George Eastman, then president of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, and a committee representing that organization, called upon me and said the City of Los Angeles was determined to make complete restitution, in so far as possible, to the victims of the flood. We explained to them the operations of the emergency organization and outlined the plans of the Red Cross to make a public appeal for funds. Mr. Eastman's committee urged that the appeal should not be made, asserting that it would be a reflection upon the City of Los Angeles, which proposed to take care not only of the emergency phases of relief but also to provide for permanent reconstruction. The Ventura County committee fully recognized the good intention of the gentlemen; but since the legal liability of the city had not yet been determined by court action, it was possible, if not probable, that the work of the Los Angeles committee would be held up by injunctions. In such case the Ventura County committee feared that the sympathies of the public, then thoroughly aroused by the terrible disaster, would die down, and make it impossible to secure the necessary funds by public appeal. The Ventura County committee, with the concurrence of the Red Cross, accordingly notified the Los Angeles committee that it was not willing to forego the public appeal for funds unless the City of Los Angeles would deposit a million dollars to meet the emergency phases of the disaster. The Los Angeles committee accepted the conditions and the city promptly deposited the million dollars. Soon after the understandings between the Los Angeles committee and the Ventura County committee on a complete and equitable adjustment of damage done, a rather serious situation arose that promised for a time to make the undertaking extremely difficult, if not impossible. This was the operation of so-called "ambulance chasers," or shyster lawyers who appeared on the scene and attempted to get assignments of claims on a percentage basis from injured parties. At that time I caused a circular to be issued which was sent to all persons known to be injured and published in all newspapers circulating in the damaged area. I quote from it as follows: In the meantime there will be lawyers and claim agents who will attempt to take advantage of the situation and sign up those who have been damaged on some contingent basis. I earnestly request that no arrangements be made with anybody to handle claims as such action will only result in complicating the situation and in reducing the amount that those injured will eventually receive. I would ask that the names of any lawyers or claim agents who are soliciting this business at this time be immediately handed to me and I will see that their names are published and that they are branded as parasites seeking to take advantage for personal gain of a situation which should call for the unselfish cooperation of every honest citizen. When the first of these so-called "parasites" appeared on the scene in the early days of the disaster, a committee, accompanied by the sheriff, took them to the county line and told them not to come back in very emphatic terms. While this perhaps savored a little of vigilante days and probably was not legal, nevertheless, in my opinion it was warranted under the circumstances. Provision for the emergency features of the disaster having thus been made, an organization was set up to carry on the work of rehabilitation, restoration, and compensation for personal injuries and loss of life. The setup of the organization was as follows: LOS ANGELES COMMITTEE: George L. Eastman, chairman; James R. Martin, secretary CLAIMS: Death & Injuries: W.B. ALLEN, chairman Damage to Land & Improvements in Country: John A. Burton, chairman Buildings, etc. in Cities: John C. Austin, chairman RECONSTRUCTION: Land & Improvements: P.M. Boggs, chairman Homes, etc.: J.C. Edwards, chairman VENTURA COUNTY COMMITTEE: C.C. Teague, chairman; George B. Travis, secretary CLAIMS: City and Country Buildings: C.C. Teague, chairman Death & Injury: Richard Bard, chairman Damage to Land & Improvements (not buildings): Roger G. Edwards, chairman RECONSTRUCTION: Homes: C.C. Teague, chairman Land & Improvements (other than buildings): J.B. McNab, chairman I should like to say at this point that never, within my experience, have I known a group of men more unselfish, more sympathetic toward the jobs they undertook, or more efficient in the execution of their responsibilities. At the first meeting of the joint committee I stated that I would be very happy to work with the group provided we had a clean-cut, mutual understanding that we were dealing with the problem of complete reconstruction and restoration, so far as that was possible, and not with the matter of claim adjustments. Such settlements are usually made on the basis of the best bargain that can be obtained, and I made it clear that I would have nothing more to do with the work if it was to be undertaken on that basis. It was thereupon agreed that we should approach the subject only on the basis of complete reconstruction and restoration, and I am very glad to testify that I believe every member of the committee, throughout the long and difficult negotiations, was governed in his decisions by the principles we agreed upon at the outset. To show the seriousness of this problem and its complications I quote from Mr. Travis' history. First, I will give you a little picture of the conditions. A hasty survey by Horticultural Commissioner Call develops that the following areas in this County were flooded: 1554 acres Citrus 367 " Walnuts 287 " Apricots 1289 " Beets, bean and hay land 675 " Alfalfa 505 " Vegetables 2915 " Pasture Land 17 " Grapes 293 " Vacant land could be used for vegetables TOTAL 7902 acres In this area all conditions will be found, from land being completely washed away, with no value left, to farming land and orchards heavily strewn with debris, in some cases piled ten or fifteen feet high; soil is badly eroded in some places, in others heavy deposits of silt and sand have been left; orchards in some cases are completely destroyed, in others partly; trees completely washed out, other cases soil washed away from roots. Questions arise as to whether trees can be salvaged or not. Personal property has been damaged in all sorts of ways, from complete loss to only partial damage. Notwithstanding the good intentions and high character of all the members of the committee, we presently faced a situation that for a time threatened to bring the undertaking, so auspiciously begun, into serious difficulty. This was the problem of the settlement of agricultural claims. In the flooded area over 500 pieces of agricultural property had suffered varying degrees of damage. These included walnut, apricot and citrus orchards, and farming lands planted to vegetables and alfalfa. In fact, as we later found, there were five distinct classes of land, with an equal number of classes of orchards, all having different values and all suffering damage in different degrees. Some soil was completely eroded, some covered with boulders and sand, some crossed by gullies and barrancas. I became convinced that the problem was so complex, particularly since the Los Angeles committee consisted of city men, mostly unfamiliar with agriculture, that there would be little chance of our committees reaching a basis of proper settlement unless we could find some means of arriving at the percentage of damage done and agreeing upon the classification of these lands and orchards by some impartial agency representing neither Los Angeles nor the Santa Clara Valley. In considering the various agencies that might be qualified to make such an appraisal, the only one that seemed adequate for the task was the Agricultural Extension Service of California, an organization supported jointly by the state and federal governments. Its representatives are known as County Farm Advisors. At the meeting of the joint committee I suggested that the Agricultural Extension Service be asked to send a group of their best qualified men to determine the damage and that they should make their estimates in percentages rather than in dollars. The Los Angeles members of the joint committee said they would be glad to consider the recommendation. An immediate decision was very important if the damage to the properties was to be kept to a minimum. This was especially true in the case of the land covered with debris which had to be removed at once to prepare the ground for summer cultivation and irrigation. In the meantime, thinking it might expedite the work, I wrote a letter to Mr. B.H. Crocheron, chief of the Agricultural Extension Service in Berkeley, describing the damage to the properties in great detail and telling him it would be necessary to classify and map the land and orchards and determine the percentage of damage each class had suffered. I emphasized the need for speedy action and said I thought it would require about twenty men, at least, some of whom must have a thorough knowledge of soils and of the various types of orchards and annual crops grown in the damaged area. I asked him if he would carefully select the men in his organization best qualified for the work and have them prepared to come without delay, if and when the Los Angeles committee concurred in asking them. I sent a copy of this letter to Mr. Eastman, chairman of the Los Angeles committee. After waiting several days without receiving a reply, I called Mr. Eastman by telephone and told him I thought we should take immediate action and asked him if his committee had decided to support the recommendation requesting the Agricultural Extension Service to make the survey. Mr. Eastman said he had received my letter to Mr. Crocheron and thought I had gone too far in writing it. I asked him why he thought so. He said that his committee already had asked Mr. George Hecke, chief of the State Department of Agriculture, to come in and do the work and that Mr. Hecke had agreed to do so. I replied: "Let's see who has gone too far. We constitute a joint committee, and all decisions with respect to this job of reconstruction and rehabilitation are supposed to be made by that committee. All I did was to suggest the agency I thought best qualified to do the work, whereas you have gone ahead and actually invited another organization without even consulting us; and the worst of it is, because of your lack of knowledge of agriculture, you have invited the wrong agency. Mr. Hecke is a personal friend of mine, but it is his job to look after the quarantine service of the state and to administer police regulations affecting agriculture. He hasn't the right kind of organization to do the work we require. If he attempts it, he will have to get his men from the Agricultural Extension Service, and that will mean confused and inefficient organization." It can readily be understood that Mr. Eastman and I did not get very far in our conversation, inasmuch as he had already invited Mr. Hecke's organization to do the job. That same day Mr. Hecke's chief deputy called on me to discuss the work we wanted done. I knew him very well and read to him a copy of the letter I had written Mr. Crocheron, describing the nature of the required survey. When I had finished he said, "You are exactly right. We haven't the men qualified to do this type of job, and I will call my chief, Mr. Hecke, and tell him so." He put in a call at once from my office and explained the matter. Mr. Hecke said he had not understood the situation and would call Mr. Eastman and withdraw his offer to do the work. A few days later Mr. Eastman telephoned me, saying his committee had decided to join in the invitation to the Extension Service to make the survey. Soon afterward the Farm Advisors arrived, set up an office, and began their survey. Each piece of property that had suffered from the flood was separately mapped and the damage described in detail. Lands and orchards were classified on the basis of type and condition. The next problem was to determine the values of the different classes of land and orchards in the damaged region. I caused a search to be made of the real estate sales in the area for a period of two or three years prior to the flood, classified the land covered by these sales according to the schedules set up by the Extension Service, submitted the list to the Los Angeles committee and asked them to check the classifications and valuations to see if they were correct. In due course the Los Angeles representatives informed us that they were satisfied that the classifications and values were accurate. We thus had a classification of the lands and orchards, a schedule of the values for the various classifications, and an estimate, on a percentage basis, of the damage each property had suffered. With this data in hand it was a comparatively simple matter to determine the compensation that should be awarded individual property owners. The joint committee had no authority from the victims of the flood to settle their claims for damages. The committee was only seeking to determine what constituted fair compensation for individual losses. Thus it is all the more remarkable that these claims were settled without recourse to the courts.

|

Citizens' Restoration Committee Report (Claims & Claimants) C.C. Teague: Ventura County Story

Survey Map, San Francisquito Canyon

Newhall Land Letter 8/1924

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.