|

|

Click image to enlarge

| Download archival scan

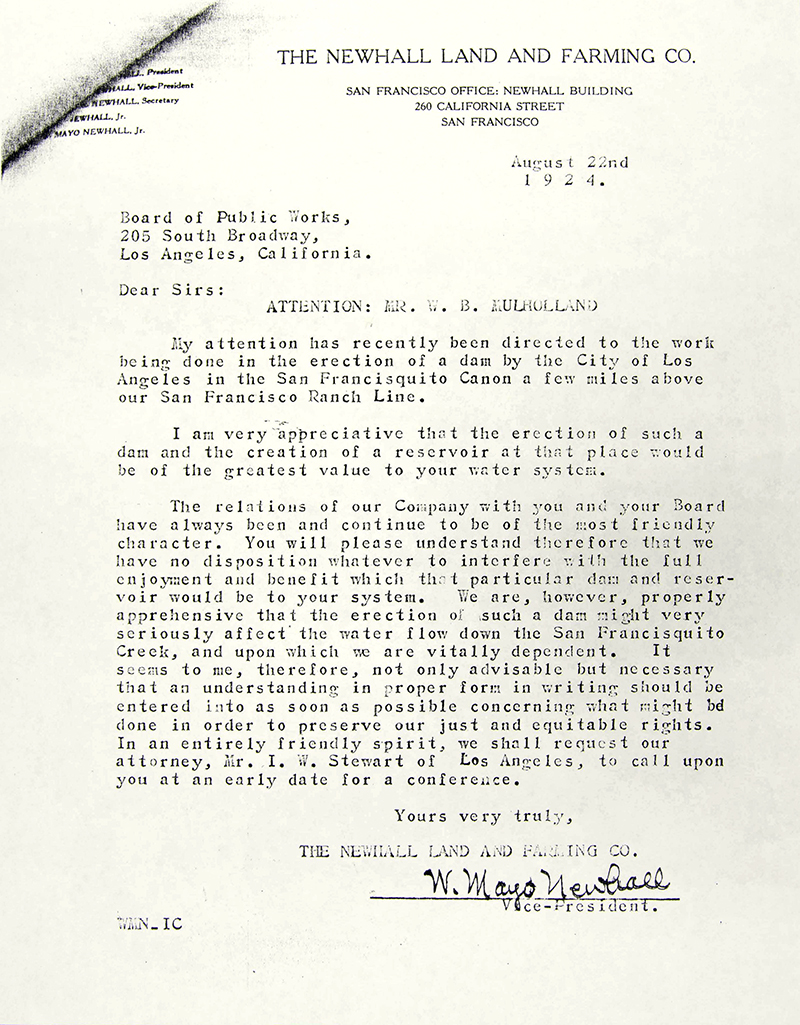

Like other downstream agriculturists, The Newhall Land and Farming Company feared the coming of the St. Francis Dam — not because it might break, but because it might restrict the flow of water they relied upon for their crops. The purpose of the dam was to impound imported water from the Owens Valley for the sole use of City of L.A. residents, but Chief Engineer William Mulholland was plopping it down on top of San Francisquito Creek, a tributary of the Santa Clara River and a feeder into the underground aquifer that the downstream farmers pumped with wells. The side effect was that the dam would stop the creek from flowing and take its water, too. On August 22, 1924, the aging president of the family-owned company, William Mayo Newhall, wrote a letter to Mulholland's attention, saying, in effect: Gee, it's swell that you're building a dam, and we won't try to stop you as long as you don't cut off our water. I'll send my people to meet with your people so we can come to terms. William Mayo didn't get the satisfaction he was seeking. Two short weeks later, on September 4, Newhall Land attorney J.W. Stewart sent a less friendly letter to L.A. City officials, claiming the dam would deprive the farming company of its "rightful supply of water" and insisting that the city "immediately desist and refrain from further construction of said dam."[1] Around the same time in 1924, Ventura County farmers had similar concerns about plans to build a dam on upper Sespe Creek — which flows into the Santa Clara River at Fillmore — and divert its flow to Ojai; and another plan to build dams and pipe water to Moorpark and Simi Valley. Charles Collins Teague, president of the influential Limoneira Company in Santa Paula, organized the farmers into the Santa Clara River Protective Association.[2] (The Association continues to exist today as the United Water Conservation District.[3]) The Sespe dam plans were abandoned, but the Protective Association was not. It turned its attention to faraway San Francisquito Canyon where, in March 1925, it sent one of California's leading engineers, Carl Ewald "C.E." Grunsky, to take a look at Mulholland's dam and evaluate its impact on the downstream water supply. (After the failure in 1928, Grunsky's observations of the dam's construction would come into play.) For whatever reason, Grunsky, in historian Charles Outland's words, came away convinced in July 1925 "that Los Angeles had no intention of storing the natural runoff waters of the canyon."[4] Grunsky was wrong. On July 14, 1926, two months after the St. Francis Dam finished construction, L.A. City petitioned the state to allow it to take San Francisquito Creek's "surplus water." Outland quotes from the subsequent Water Rights Board hearing:

The flow of the creek and river during the winter season serves to replenish the water of the San Francisquito Creek bed and the Santa Clara Valley; and the impounding by the city of the waters of San Francisquito Creek by means of its reservoir will have the effect of preventing the underground flow and seepage of the Santa Clara and its tributary, San Francisquito Creek, from being annually replenished, and protestants will thus be deprived of sufficient amounts of water for beneficial agricultural uses and domestic purposes.[5]

Hogwash, the bombastic Mulholland roared. Fine, the head of the Water Rights Board said. If you really think the "surplus" water of San Francisquito Creek doesn't feed into the alluvial aquifer and just flows out to the ocean unused, we'll put your theory to the test. Or words to that effect. The idea was to conduct a "percolation test" to determine whether the water really flowed to the ocean or, instead, was absorbed into the sands and gravels of the canyon where it joined the aquifer. True to form, Mulholland retorted: "That water will go down the canyon so fast, you'll need horses to keep up with it!" The test was conducted Wednesday, September 15, 1926, at the cool morning hour of 6 a.m. Outland writes: "Water was released from one of the five outlet gates that had been built through the dam, and by 7 a.m. the flow was regulated and measured at 100.5 cubic feet per second (cfs), a volume equivalent to that produced by fifty average wells in the Santa Clara Valley."[6] Hours later, probably down by Castaic Junction, Mulholland's deputy, Harvey Van Norman, was still waiting. The water never came. "Well, there go Bill's horses!" Van Norman famously lamented. The test continued the next day and the next with 50 percent more water. By the morning of the 18th, "a total of 775.28 acre-feet of water had been released, but not one drop reached the Santa Clara River [above ground], the entire amount being absorbed by the water gravels of San Francisquito Canyon."[7] Teague and the Santa Clara River Protective Association went to court, and the dispute still had not been resolved by March 1928 when the dam collapsed and the downstream farmers suddenly had more water than they could handle. Teague would chair the Ventura County Committee that was created to ensure that the City of Los Angeles paid all valid death and disability and property loss claims in that county. Arthur Chesebrough, Newhall Land's ranch manager, was a member of the committee; then as now, Newhall Land's property straddled Los Angeles and Ventura counties. In the end, Newhall Land was the single biggest recipient of monetary compensation for losses suffered in the dam disaster — $737,039.59. The check from L.A. City arrived in 1930. Historians agree Newhall Land wouldn't have survived the Great Depression without it.[8]

1. Hundley, Norris Jr., and Donald C. Jackson. "Heavy Ground: William Mulholland and the St. Francis Dam Disaster." Oakland: University of California Press, 2015: pg. 99 and fn.38, pg. 367. 2. Outland, Charles F. "Man-Made Disaster: The Story of St. Francis Dam." Glendale, Calif.: The Arthur H. Clark Company, Revised Second Edition 1977: pg. 26. 3. Hundley et al., ibid., pg. 99. 4. Outland, ibid., pg. 38. 5. Ibid., pg. 39. 6. Ibid., pg. 40. 7. Ibid., pg. 42. 8. Newhall, Ruth Waldo. "A California Legend: The Newhall Land and Farming Company." [Valencia, Calif.]: The Newhall Land and Farming Company 1992: pg. 116.

OV2401: 9600 dpi jpeg from original letter in Oviatt Library, California State University, Northridge. Courtesy of Lauren Parker.

|

Citizens' Restoration Committee Report (Claims & Claimants) C.C. Teague: Ventura County Story

Survey Map, San Francisquito Canyon

Newhall Land Letter 8/1924

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.