|

|

|

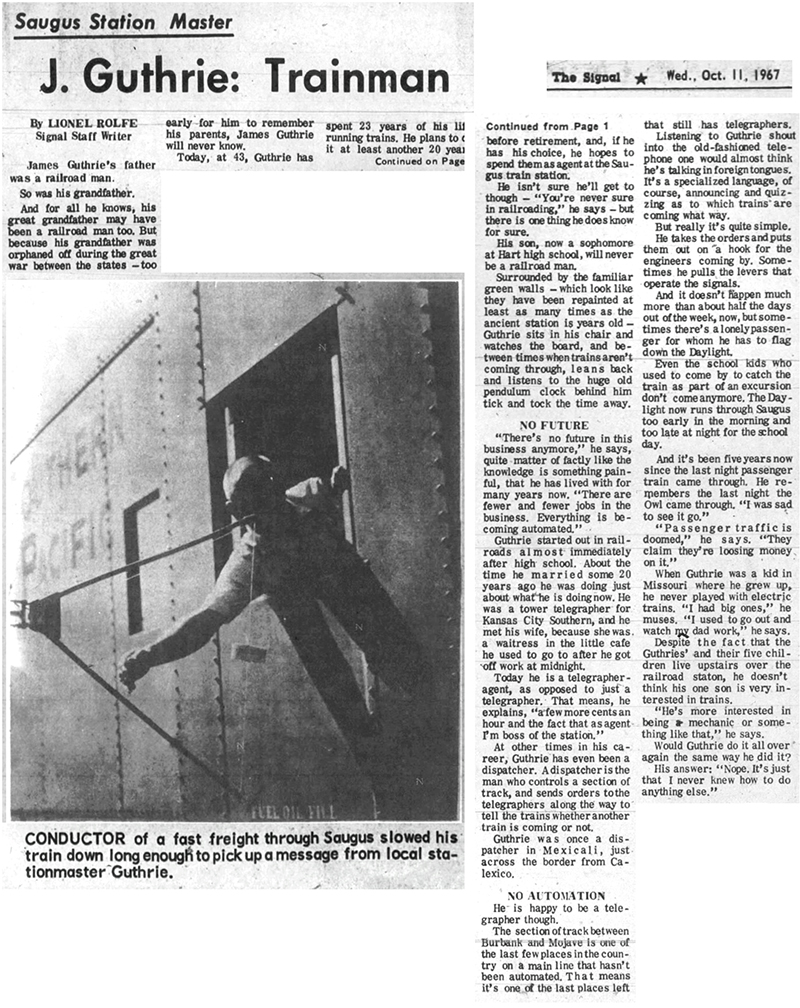

Signal archive photos (2x2-inch negatives), photographer unknown. October 10, 1967 — SPRR Saugus Station Agent James R. "Bob" Guthrie uses train order hoops to send train orders — written instructions — to a passing Southern Pacific freight train. Note that there are two train order hoops, an upper and a lower; the orders in the upper hoop are snatched by the engineer in the locomotive, while the lower are retrieved by the conductor in the caboose. Most of the country was automated by 1967, but not the Burbank-to-Mojave line, which included Saugus. Train orders were still sent the old-fashioned way. Guthrie, who was both the station agent and a telegrapher, would receive the latest road news by telegraph — maybe a late or unscheduled train here, or a malfunctioning switch or closed siding there — and then type up the information on train order forms (as seen in last two photos), fold them up and loosely tie them with a string to the order hoop. The train would usually slow down but not stop. If the engineer happened to miss his mark, there was a duplicate set of instructions for the crew in the caboose. The feature story below suggests that by 1967, the Southern Pacific's San Joaquin Daylight passenger train no longer made regular stops at Saugus. It was on-demand only; Guthrie would flag down the train to pick up the odd passenger. Passenger service at Saugus ended entirely in 1971; freight service ended in 1978, and the depot closed. In 1980, the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society acquired the building from the Southern Pacific Railroad and moved it to William S. Hart Park in Newhall.

Download original images here. Signal Photo Archive, Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society collection.

|

See Also:

Docent Training

Opens 6/21/1888

Exterior 1890s

Track View 1907-12

1910

1914

2 Wells Fargo Express Trucks at Depot 1919

2 Locomotives at Depot Late 1910s

1930s-1940s

"Oh, Susanna!" 1936

8/23/1936

1938

May 1941

Depot Screenshots in "Suddenly" 1954

Sending Train Orders 10/10/1967

1967-1970

1967-1970

1970

1970

1970

1970

Snow Day 12/19/1970

Train Orders 11/1978:1

Train Orders 11/1978:2

Train Orders 11/1978:3

"Supertrain" NBC 1979: Interiors, Exteriors

4/17/1980 Mult.

New Signage 2018

Crossbuck Reinstalled 2021

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.