|

|

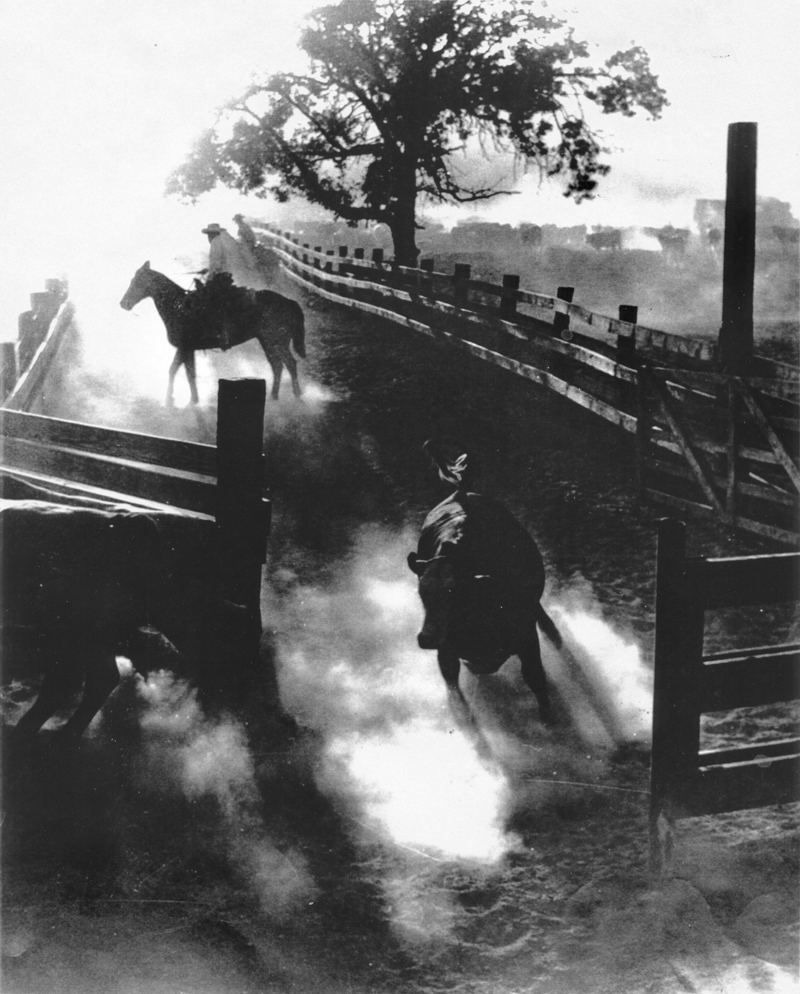

Where Once Were Cattle...

By RUTH WALDO NEWHALL, Gazette Correspondent.

Old Town Newhall Gazette, Spring 1997.

|

The Magic Mountain parking lots, where five thousand cars disgorge their passengers today, held no cars 32 years ago — but accommodated 13,000 to 17,000 steers, which jostled each other as they fed from troughs heavy with grains and vitamins. Here were the feed pens of The Newhall Land and Farming Company, where the steers, which had been living on the wild grasses of the hill ranges, were brought to be fattened and sold. A few of these steers were born on this ranch, but most were brought from other ranches and trucked in to be "finished" for market. The building of Valencia, also on company land, meant the end of the feeding pens and the beginning of Magic Mountain. It was symbolic of a changing California culture, a culture born and weaned on cattle. There was no room for livestock near the carefully planned New Town of Valencia. As one planner remarked, "You can't expect people to live downwind of 14,000 cattle." Thus came the near-total demise of the longtime mainstay of California's economy. This was once cattle country. The padres at the San Fernando Mission brought in animals originally imported from Spain, beginning in the last decade of the 1700s. It remained cattle country until the population explosion of the 1950s and 1960s filled the San Fernando Valley with subdivisions and found people spilling over the hill into what we now call the Santa Clarita Valley. On the great ranchos of Southern California, the raising of cattle was the only business. For years most of the meat was thrown to the dogs or buried. The small fraction of the beef that was consumed was cut into long strips and dried in the sun to make jerky -- good exercise for jaw muscles. The cattle were raised primarily for their hides, known to seamen as "California bank notes." They were loaded onto ships and sent to New England, where people farmed in the summer and spent their winters converting the California hides to shoes and boots and saddles. However, as quickly as it had exploded, the California cattle boom of the 1850s collapsed. It didn't take long for cattlemen from Texas and the Midwest to move into the area where all the hungry hordes of gold seekers had landed, east of the San Francisco Bay. They drove their cattle to the valleys nearest the gold fields and the city, shutting off the southern rancheros. The local cattle business had prospered mightily through 1855, but in the following year the population growth slowed while the cattle population swelled. Supply out-paced demand. Cattle prices fell from $75 a head to $16, then down as low as $3. By 1860 there were ten times as many cattle as people in California. The end of the profitable cattle business, whether for hides or meat, meant the end of the rancheros and the takeover of the great ranchos by the Yankees. The natives who lived in California before the first Europeans arrived in 1769 had no domestic livestock. The hills were inhabited by wild deer, fearsome bears, and a host of small game that constituted the principal protein source for the Indians. Yet only thirty years after the first Spaniards brought small-boned black cattle to San Diego, historians estimate that there were a million cattle on the California ranges. The cattle influx to California in 1800 more than matched the arrival of gold seekers fifty years later. The rolling hills of the Coast Range, covered with wild grasses, were ideal for free-ranging herds. It led to a life more suited to the Spanish temperament than grubbing vegetables. Indians were taught in the missions how to grow corn and other food crops while the Spaniards enjoyed life on horseback, riding over their vast acres. The largest land grants in the area were 48,000 acres — about 75 square miles — and the Rancho San Francisco, which included much of the Santa Clarita Valley, was one of these. All the owner of a rancho had to do was bring in cattle and let nature take its course.take its course. Rancho San Francisco passed through the hands of various creditors until it was purchased in 1875 by Henry Mayo Newhall. Like the half-dozen other ranchos purchased by Newhall, who had made a railroad fortune, the Rancho San Francisco continued in its traditional role as a cattle operation. As a vice president of Southern Pacific, Newhall had bought the ranch as the rails were approaching from north to south. From this ranch he would be able to ship his cattle conveniently to San Francisco, the major port and major market of the West, ten times the size of the rural town of Los Angeles. Newhall, his sons, and their sons assumed the Santa Clarita Valley would remain a cattle ranch. The valley was a giant grazing area, surrounding the hamlet of Newhall and some scattered farms in Saugus. The cattle were still visible on the hills when, in 1935, large oil fields were discovered under the Rancho San Francisco, now renamed the Newhall Ranch. It was a local saying that "nothing makes a steer fatter than grazing under an oil rig." Where there had once been more cattle than people in California, in the mid-20th Century the trend was reversed. Cattle were no longer an unlimited population left to graze on the hills, and the new city dwellers wanted quality beef. Feeding pens sprouted on the Newhall Ranch. As many as 30,000 steers a year were brought in from the ranges to be fattened and turned into prime -- and high-priced -- beef. Now the cattle dined on a carefully-balanced mixture of grains and vitamin-enriched foods, mixed in a central mill and dumped into the feeding troughs by mechanical carriers. But the people kept coming, and the cattle had to move away again -- away from Valencia and Magic Mountain and other innovations not in tune with a livestock environment. The cattle themselves changed radically from the small, black, white-horned, nimble animals that occupied the earlier ranchos. Now they were the heavier breeds: white-faced Herefords, black Angus, cross-breeding with each other and with the big-boned Brahmas. They are trucked in to the local hills in October or November when they are six to eight months old and weigh an average of 400 pounds. These yearlings are now grazing, bringing their weight up to 650 or 700 pounds, and in May or June they will be shipped to feedlots in the Midwest for their final fattening before going to market. Then the local ranges will house only 200 cows and their newborn calves. Many people would be surprised to know that today there are still cattle nearby. During much of the year the animals are on the hills just west of Interstate 5. There are more than 5,000 during this lush early spring season, half of them (belonging to the Tejon Ranch) just north of Route 126, and half (belonging to Newhall Land) on the south side of the highway. Passersby cannot believe there are several thousand cattle in these hills, because the animals tend to gather in the canyons away from the road and are rarely visible. There are some permanent residents, too — or as permanent as cattle ever get. That is a herd of cows, which once a year, until they are eight or nine years old, produce calves for the ranges. Newhall Land, on whose land the 5,000 cattle are feeding, has cut its staff down to one cowboy. The unusually fine growth of range grass this year means the cattle will be left on grass longer before they are trucked away to be fattened in the distant feed yards. Lush grass does not necessarily gladden a cattleman's heart, however. It often means that since beef is abundant, prices decline. The standards for cattle change, too. Where once growers aimed for huge steers which, when fattened, weighed up to 1,300 pounds, today the trend is toward small, leaner animals of 800 pounds, nearly back to the weight of the Spanish steers. Words like "saturated fat" and "cholesterol" have their impact on the ranges, and the cattle business is experiencing another revolution. As the ranges were succeeded by feedlots, and the Rancho by the City of Santa Clarita, so have the steers been replaced by people. It is the California story. ©1997 Old Town Newhall USA/SCVHistory.com | All rights reserved.

|

H.M.N. CATEGORIES:

Story by Ruth Newhall

Harvest 1897 x3

~1900 x2

Sheep ~1940s

Sheep ~1940s

Feed Lots 1941 x2

Irrigation Pond 1940s

Picking Onions 1972

Cookbook 1984

Medfly Eradication 1989-1990

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.