|

|

Special Memories Of Pico Canyon, 1948-53

Today we call it Mentryville. In the writer's day, it was simply Pico Canyon.

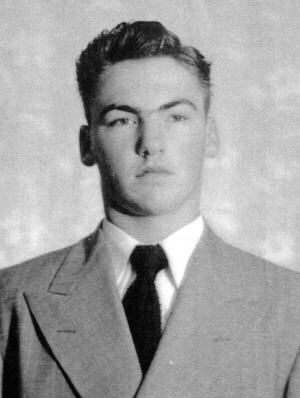

By BILL RUNDBERG.

Old Town Newhall Gazette | July 4, 1997.

|

By the spring of 1953, jitterbugging was out, rock and roll was on its way in, development of the valleys was still accelerating, the three-year-long war in Korea — officially a police action — would end in a few months, and TV, now into Newhall, also reached into Happy Valley. The population of Mentryville had risen from two to nine and was now down to three. Land development, wider roads and electronic communication had brought Newhall a little closer to metropolitan Los Angeles. And after five years of connection with the outside world through the comings and goings of teen-agers, Mentryville was a little closer to Newhall. Sometime in the spring of 1948, my father took me for a ride to Pico Canyon. We lived in Granada Hills then, and he was working for the Standard Oil Co. out of Martinez Canyon. He had leased the Pico Canyon property around Mentryville, and we were to move into the Big House in summer. We were five then, including my father, Joe Rundberg, my mother Helen, my sister June, and Doug Higley, a friend who lived with us. We kids were transferring from San Fernando High School. Doug would graduate from Hart High in 1949 with the first graduating class. June was in the class of 1950 and I in the class of 1951. The population of Mentryville was about to increase from two to five. On that day, we turned west off of Highway 99 at the intersection of Lyons Avenue. I was in new territory. The next three miles would soon become very familiar: Up the hill past the Hoags' place, down again and along the south edge of a field, across the bridge, past the cliffs on the right, then past the Wickhams' canyon and the Larinan place on the left, Dead Cow Canyon on the right, left at the Y and a quarter mile or so to the gate. The view there was framed on the left by old buildings — a barn, chicken house and garage — and on the right by a row of olive trees and an enormous eucalyptus tree. They screened the view of the Big House. Up the road and in the background were pepper and eucalyptus trees that had shaded earlier buildings. The gaps were filled in by dirt, dry grass and brush. The remaining collection of buildings at Mentryville consisted of the Big House — we didn't call them "Mentryville" or "Big House" then, just "Pico Canyon" — with its ice house and laundry shed; the barn, chicken house and garage; a small house and barn with a corral across the creek; and the school house. Attached to the barn by the gate was a milking shed and a wooden corral. The house across the creek was accessible by a footbridge, the small barn by a road across the creek bottom. When we moved into the Big House we replaced the Woolridges there. Josh Woolridge had retired and moved his family to Encinitas. John McDermott (known as "Mac") used the barn across the creek to store feed for the few cattle and horses he ran on the lease. In prior years, the Woolridges had lived in the house across the creek, and before them, the McDermotts. When we arrived, the McDermotts lived in the house near the Pioneer Oil Refinery at the mouth of Railroad Canyon. My first look at the Big House registered its tired condition, gray exterior, spacious porches, high ceilings, transoms over every door, gas chandeliers in every room, four gas fireplaces framed by wooden mantelpieces with plate glass mirrors, pull chain toilets, cast iron claw-foot bathtubs, alabaster wash bowls and very little provision for electricity. Before we moved in, Standard Oil had some of the interior painted. My mother papered the dining room with wallpaper that has since been covered with several other layers. We installed a 1500-watt power plant in the laundry house and so had an electric light in the kitchen, electric lights and radio in the living room, a light on the front porch, and power for an electric iron and washing machine — but not at the same time. The power plant and gas lights were fueled through a line from an otherwise-unused well. Kerosene lamps provided the rest of our indoor light. We brought with us a dog, cat, over 100 chickens and a dozen or so turkeys. Most of the chickens that roosted outside at night soon got picked off by various predators. Our flock was thinned to a few dozen that were circumspect enough to choose the chicken house for their nights. Our dog Topsy never got used to being teased by the foxes.

When we moved in, the other homes accessed through Pico Canyon were those of the Bordens on the Barnsdall Oil Company's Potrero Lease (bear right at the Y instead of left); the Larinans — theirs was the only house visible from the canyon road between the Hoags and the Standard Oil property — and the Wickhams, in a canyon behind the Larinans' place. Judy and Barbara Borden went to Hart High. Barbara and my sister June were in the same class; Mike Larinan and I were in the same class. In 1949, Charlie and Violet Thurman and their children Charlotte and Dennis moved into the house across the creek. They fixed it up and got their electricity from a war surplus power plant. When "Mac" McDermott died a year or so later, they moved into the Railroad Canyon house. New occupants of their Pico house would be Walt and Bernice Schultz and their children Melvin and Van. Both families were good, lively company. Sometimes the three couples cleared the kitchen in our house and danced. The kitchen, large for its intended purpose, was small for square-dancing, but that didn't stop them from improvising. Soon after our arrival, a practical joke produced a goat, fresh with milk, tied to the barn. We bought a calf at a dairy in Placerita Canyon and started him on the goat's milk. Then we bought a milk cow. Now our mornings and evenings included feeding and milking the various creatures. I raised several calves and spent my summers working on projects around the place. A roustabout crew dug a pit, and I assembled a homemade cattle guard (where the heavy-duty one is now) from salvaged 8-by-8's and 2-inch pipe. Replacing the horse block and stairs outside the front gate chased out a king snake, rattlesnake and tarantula. We used 2-by-6 redwood staves from a collapsed water tank to replace the old, rotting picket fence. I maintained a vegetable garden on the north side of the house and made a lawn on the south side under the black walnut tree. I tinkered with cars and pursued other ventures. In 1952 I worked in a summer roustabout crew over the hill on the Sunray Lease. During summer June usually worked in San Fernando or at the Bermite powder plant. My father had been a production foreman at Martinez Canyon. While at Pico he drove regularly to Santa Paula, Oxnard, Ventura, Santa Barbara and Santa Maria, as well as to Placerita Canyon and the mountains north of the San Fernando Valley. He logged over a thousand miles a week and put in long days. Pico Canyon, also part of his territory, was a stopping place between these extreme locations. Fire was a major concern. The canyon was hot and dry for several months of the year — clearing for firebreaks was a regular spring activity — and oil workers did the bulk of the work in extinguishing oil well fires. Domestic fire companies were not equipped for that. During our time there, fire did not threaten Pico Canyon directly. But my father was involved in fighting several oil field fires, including one where he and two co-workers worked steadily for more than 24 hours to cap a well near Oxnard that had blown out and caught fire. At one point during my father's early days with the company in Baldwin Hills, Bill Cochem was his foreman. They kept in touch for decades after that. Bill, whose father once operated the bakery in Mentryville, had grown up there and worked in the oil field as a gangpusher when he was 16 years old. While we lived there, Bill's brother Paul occasionally visited the canyon during deer hunting season. The quiet, the open space and the shade made Pico a wonderful spot for large family gatherings. We had a lot of extended family in and near the San Fernando Valley. The space we had was lavish: a large house with big porches, plenty of shade, and picnic grounds up the canyon. My mother organized many meals on holidays. In August, 1952, June married Wayne Hamaker, also Hart High '50, in a simple, beautiful lawn ceremony. Friends decorated the black walnut tree with flowers. For music we used the piano in the den. It was the room downstairs on the southwest corner. The pianist played loudly. People dressed up as much as the heat would allow, certainly more than I saw during the entire rest of our time there. Shade from numerous pepper and eucalyptus trees and the ever-present quiet inspired walks around Mentryville — common entertainment for guests. My mother enjoyed solitary walks up the canyon road. Beyond that, hills and shady brush proved favorite routes for exploration. Gas bubbled and water flowed from an abandoned well in a canyon behind the site of Cochem's bakery. To the east was a hiking route to the Wickhams' canyon which included an eastward view toward Newhall. Summer evenings were a time for sitting on the porch and talking, often with the power plant off. On cold evenings we were inside, probably reading, perhaps listening to one of the very few radio stations that reached us. Despite the limited reception, we never seemed to want better reception enough to simply rig up a long antenna. My parents were readers and enjoyed the quiet. Sometimes we played a 78-rpm record from our modest collection that ranged from Tchaikovsky to Lawrence Welk to Frank Sinatra. For me, the technology around the house was much more interesting than what most folks had: gas lights, a hand-cranked phone, gas refrigerator, an electric power plant that started up on demand, old-fashioned plumbing, kerosene lamps, an ice house we never used for its intended purpose, and various other artifacts from earlier times. My mother used an egg beater to make butter from the cow's cream and used the jar from the old butter churn to cure the olives we picked from our trees. To make ice cream for parties we used a large, three- or four-gallon hand-crank freezer. The Larinans' house was also interesting: gas-powered washing machine, a radio that used an automobile storage battery, a Coleman gasoline iron, and kerosene lamps. In the canyon behind the Larinans, the Wickhams lived in a small house and had a power plant. A secondary and much older building there was the first private adobe home I had ever seen. I have forgotten its history. While shy of electricity, plumbing and wooden floors, it was very cool on hot summer days. Up Pico Canyon, relics of the old days of oil production formed a large, nearly-private outdoor museum. There were remnants of derricks, maintenance sheds, offices, and mementos of daily work such as gloves, notebooks, hand tools and supplies. I would walk around the abandoned facilities for hours. I thought it should be declared a museum but never did anything about it. In a back room of the house, apparently once the maid's quarters, were some company records and pictures of the oil field in early days. The two central power plants for the pumping wells were marvelous contraptions. Each had a horizontal, single-cylinder, large-bore engine with a cast iron flywheel more than six feet in diameter. Each turned a vertical shaft, at the top of which was mounted a large, wooden wheel with its axle vertical and offset from the shaft. Fastened to the rim of the wheel were cables called "jack lines" that were draped across the hills in all directions. They were supported on standards that looked like gallows marching off along radial paths into the distance. At the end of each cable was a primitive pumping unit. As the engine chugged and the shaft turned, the wheel tugged on the cables. Each cable in turn pulled on a lever, thereby executing a stroke of its well. When we lived there, most of the plants and machinery were still there but badly deteriorated. Some of the standards remained. While I could only imagine the sight of the operation in Pico Canyon, I saw, later, in the 1960s, such a system working in the San Joaquin Valley near Maricopa. There had been other such systems in Kern and Ventura counties. It was the story of "Mac" McDermott's attempt to repair a jack line in Pico Canyon that explained his mustache. Years before we knew him, he had tried to reconnect a broken cable and was hit in the face by a comealong that loosened as he pulled the line together. Hence the mustache to cover the scar. At the top of the canyon, around 1950, exploration resumed. Union Oil Company drilled on the Odeen Lease, which was accessed through Pico Canyon. The well site was a short distance beyond the end of the canyon road and offered a magnificent view of territories around Newhall. At home, our telephone line — Newhall 8761F4 had recently been the only party line — would now be shared with the drilling rig. Sometime in 1951 or 1952, the Schultzes achieved a Mentryville "first": They brought home a television set. The next "first" would be getting a recognizable picture. Walt tramped up and down the hills behind their house and across the road outside the gate, carrying an antenna and dragging lots of wire. After a fair amount of shouting and channel-switching, he found a spot behind their house that got enough signal bounce to bring some evening entertainment, albeit through a little "snow." And so we were introduced to TV entertainment with Spade Cooley, Lawrence Welk and other programs I have since forgotten. Shortly after our 1948 arrival, Mike Larinan introduced me to the Boogie Beat, a malt shop across the street from Hart High. Later, June, Doug and I would expand our Newhall social life to include the soda fountain at the Williams' drug store (Newhall Pharmacy), the Snack Shack and the American Theater. The Fourth of July saw a parade with local color and events at the Melody Ranch movietown, aka "Slippery Gulch," in Placerita Canyon. The latter was set up for the day with concessions, entertainment and food. The total enrollment at Hart High was about 600 students in grades 7 through 12, this in a district that reached into the many canyons near Newhall, up toward the Ridge Route and out toward Antelope Valley. So any particular collection of friends might have had representatives from several canyons. Active high school life involved considerable driving. Distances to the league schools — Fillmore, Santa Paula, Antelope Valley, Oxnard and Ventura — were exceeded on game trips to Taft, Barstow, Victorville and other faraway places. Given the distances up the various canyons, many of us were farther apart from each other than we were from Hollywood. A double date involving a movie on Hollywood Blvd. and burgers afterward at a Bob's Big Boy drive-in in the San Fernando Valley could require as much as 200 miles of driving, much of it on two-lane roads. The only freeway was a short run near Hollywood in Cahuenga Pass. My parents had some marathon evenings of their own. They liked to square-dance, locally and as far away as Lancaster. They also liked to dance to Lawrence Welk's music in Santa Monica. Occasionally they fit both into one evening. In 1951-53, there were times when I came home at midnight and was the first one in. The canyon was dark, and the only acknowledgment that I had been out for a good time was the crowing of a rooster when the car lights shone on the chicken house. In contrast to the quiet life in Pico Canyon was the oil rush in Placerita Canyon for about two years beginning in 1949. "Confusion Hill" was the setting for bizarre happenings and stories about frantic oil drilling, sabotage of oil wells, renegade road building and gun-toting property owners patrolling on horseback. My family attachment to the oil business brought plenty of news about that. Accompanying this was news of the beginning of the Korean War in the summer of 1950. Some young men considered joining the military instead of waiting to be drafted, and the rest talked about who was considering it. Doug eventually went into the Army. At age 15, my concern about the news faded daily when I returned to Pico Canyon with its sleepy pace, sketchy radio reception and big, starry skies. Confusion Hill seemed even more an aberration than it was, and world events described in newsprint seemed very far away. But I began to pay attention when talk of war increased and news hit about acquaintances going to Korea. In the fall of 1950 I went to a meeting of the Hart High PTA to make a case for including in our curriculum the study of contemporary Russia and China and of communism. I made the case for learning about the outside world and understanding our adversaries. The response was a mix of silence and polite thanks, but no encouragement for discussion except from my civics teacher, Cecil Sims. We were, after all, well into the Cold War. So back to Pico Canyon. Early in 1953, our life in the canyon was changing significantly. June and Wayne were living in Newhall. The Schultzes left the company, packed up everything including the TV set, and returned to Texas. Doug was stationed in Korea. In late spring, my father transferred to Standard Oil's Murphy-Coyote lease in La Habra. I was finishing my second year at Valley Junior College in Van Nuys and, at the ripe old age of 18, had decided on a hitch in the military. We moved to La Habra in May. The cat died and the dog ran away. I entered the Army on July 23. The Big House awaited its next occupants. They were to be the Thurmans. We left behind the makings for many other durable memories of Pico Canyon and Mentryville: Sitting on the porch at dusk and talking as the nightbirds and bats started their evening show; early spring marked by hens bringing their chicks in from secret nesting places, only to lose most of their flocks to predators; the winter of 1949 with its foot of snow and school canceled for a week while we tobogganed on Mustard Hill; the blood-curdling scream of a mountain lion passing through at night; near misses with rattlesnakes; days of solitude during summer work; morning promenades of chickens walking up the canyon road before the heat descended on us; the clucking of turkeys as they closed in on a snake; squirting milk from the cow into the mouth of a begging calf; spring after a wet winter when the mustard weed grew six feet high; the "come back here" call of quail unseen among brush and weed; the top of Mustard Hill, a vantage point for watching sunsets and viewing the enormous outcropping that, according to Eldon Wickham, is the Topa Topa Fault; a bright moon redefining the canyon in terms of its shadows. And the people: Lots of chat on many subjects with the Thurmans and Schultzes; shooting the breeze with the pumpers on their daily runs up the canyon; the gentle strength and good company of Dorothy Larinan; learning about local geology and flora from Eldon Wickham; June and her girlfriends climbing from her bedroom out onto the porch roof to sunbathe; tired talk on long bus rides home after school activities. Solitude and work in Mentryville provided a backdrop for our busy high school lives. I have special memories of high school mathematics teachers Hugh Gilmore and David Lefever, who supplied direction for my involvement with, and eventually teaching, mathematics; English teacher Norma Lewis, probably my most important role model in my decision to teach, and who was a major influence in my enjoyment of literature and language; Lois Phillips, a demanding teacher with whom the learning of Spanish was great fun; Cecil Sims, civics teacher and student government advisor, with whom I spent much enjoyable time. June lives in Northridge now. Doug died last year. Our parents are in Granada Hills. My own family and I have been living in San Mateo since 1967 and, before that, in various suburbs since 1956. During the 44 years since we left Pico Canyon, the time from 1948 to 1953 has been for me a nourishing source of memories, a checkpoint in contemplation of priorities, and a resting place for emotions: Good support for life in a much busier world. Bill Rundberg is an educator in San Mateo, California. Click here to visit The Friends of Mentryville. ©1997 Old Town Nehwhall USA/SCVHistory.com | All rights reserved. |

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.