|

|

Placerita Gold

Sutter and Marshall knew they weren't the first to discover gold in California.

By Leon Worden

Santa Clarita Valley Living Magazine | February 2006

|

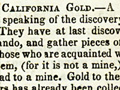

If you studied California history in grammar school in the 1950s, '60s or '70s, you might have come away thinking the first gold in the state was discovered at Sutter's Mill in 1848. It was, after all, an important discovery, and it triggered the biggest westward migration the young nation had ever known. But if you — or your child — studied California history in the 1980s or '90s, you probably know that on that brisk January day in 1848 when James Marshall pulled his famous nugget from the tailrace of John Sutter's sawmill, it wasn't exactly a "first." Since 1975, when the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society was organized, local elementary school teachers and local historians have been collaborating to teach the "real" California history that's often glossed over in textbooks. Today, nearly every third grader in Santa Clarita learns that the first authenticated discovery of gold in California was made in 1842, right here in the Santa Clarita Valley. Why the disparity? How can we be right and everybody else wrong? The simplest explanation is that teachers and textbook writers in other parts of the country are aware of the importance of the Sutter's Mill discovery — and then leap to the erroneous assumption that it was a "first." The mistake isn't limited to "foreign" (non-SCV) educators. No less a figure than John Wayne fell into the same trap of faulty logic in February 1978 while taping a commercial for Great Western Bank. In the voice-over, he referred to California's "first" discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill. Wayne should have known better, considering that in the 1930s and '40s he shot many films just a stone's throw from the 1842 discovery site. In fact, Wayne did know better — and in a letter to the local Historical Society, he graciously acknowledged his gaffe. "I don't know whatever possessed me to use the word 'first' in that commercial," Wayne wrote. "I have kicked horses up and down the hills around Placerita Canyon and stepped on every foot of it. Matter of fact, they built that Western street that used to be there off my back, so I certainly knew that the first gold was discovered in Placerita Canyon." There's a second reason some of the lazier writers of U.S. history books get it wrong. Marshall's discovery was an "American" discovery. Ours wasn't. Within weeks after Marshall's 1848 discovery, the United States and Mexico ended their two-year-old war, and California became a U.S. territory. California was still part of Mexico on March 9, 1842, when Francisco Lopez spied some nuggets along Placerita Creek. Gold had been mined for centuries in other parts of Mexico, so Lopez's discovery was not a particularly big deal at the time. But it was nonetheless the first "documented" discovery of gold in California. The "document" was the petition for mining rights that Lopez and his associates filed with California's Mexican governor, Juan Batista Alvarado, a month later, on April 4. The document resides in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. And still the Marshall-Sutter myth persists. It's like a bad urban legend that just won't go away. Try telling folks in the vicinity of Sutter's Fort — the Sacramento area — that "their" discovery wasn't California's first, and you're likely to get laughed at, or worse. But the joke is on them. John Sutter and James Marshall knew about the Lopez discovery. They knew miners were pulling nuggets out of Placerita Canyon — years before hitting paydirt themselves. They learned about it in 1845, a year before the Mexican-American War. Manuel Micheltorena had succeeded Alvarado as governor of California. Micheltorena was immensely unpopular and Alvarado mounted an insurrection. Who should take Micheltorena's side but John Sutter. Alvarado prevailed. He drove Micheltorena back to Mexico "proper" in a one-day battle that cost no lives — but not before throwing Sutter and his right-hand man, John Bidwell, into a prison near the Mission San Fernando. Sutter and Bidwell were soon released. Bidwell headed north through Placerita Canyon and observed the gold mining operations, vowing to hunt for the metal upon his return to Sutter's Fort. When Bidwell got back to the fort, he met a new arrival — Mormon pioneer James Marshall. Frankly, Bidwell needn't have witnessed the gold-mining operations first-hand to know about them. They weren't exactly a secret. Three years earlier, on Oct. 1, 1842, the New-York Observer — an abolitionist newspaper published by Sidney Morse, younger brother of Morse Code inventor Samuel Morse — carried the following news item: "A letter from California, dated May 1, speaking of the discovery of gold in that country, says: They have at last discovered gold, not far from San Fernando, and gather pieces of the size of an eighth of a dollar. Those who are acquainted with these 'placeres,' as they call them, for it is not a mine, say it will grow richer, and may lead to a mine. Gold to the amount of some thousands of dollars has already been collected." So what happened? Why did Americans flock to San Francisco and Sacramento after the war with Mexico, and not to Placerita Canyon? Because the northern gold fields were far richer. By 1849, Placerita Canyon had essentially played itself out. (Small-time mining operations continued into the 20th Century, and tiny flakes still show up today in Placerita Creek after a good rain.) If your friends from northern California still aren't sold, direct them to the records of the state of California — specifically to the description of California Historical Landmark No. 168. The landmark is the Oak of the Golden Dream where, according to the official records, "Francisco Lopez made California's first authenticated gold discovery on March 9, 1842." The historic marker sits under the canopy of a gnarled, hollow oak tree on the grounds of Placerita Canyon State Park. There's a chance it isn't the right tree ... but that's another story. ©2006 VALLEY LIVING MAGAZINE & LEON WORDEN • ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

Dissecting the Dream: Fact, Fiction & the Golden Oak, by Alan Pollack

New York Observer 10-1-1842

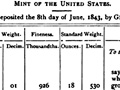

U.S. Treasury Voucher 1843

Abel Stearns Letter 1867

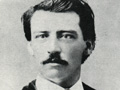

Francisco Lopez

Pedro Lopez (Brother)

Maria Felis (Wife)

Maria Concepcion (Daughter)

Francisco Ramon (Son)

Catalina (Pedro's Daughter)

Francisco "Chico" Lopez Obituary 1900

As Told by Jose Jesus Lopez

Sutter's Fort Error 1905

Prudhomme 1922

Engelhardt 1927

Francisca Lopez de Belderrain

Belderrain Story 1930

Who's Who, by Belderrain

• Story: Sutter, Marshall Knew They Weren't First

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.