|

|

Exactly Why Did Saugus Elementary School Close?

News reports, January-February 1978.

|

Webmaster's note. One "fact" that "everybody knows" in Santa Clarita is that Saugus Elementary School was shut down in 1978 because of the cancer-causing fumes that the Keysor-Century Records plant across and down the street was belching out for years and years. But that's not entirely accurate — or at least it's not the whole story. It omits a major piece of history. A more correct headline would read, "Parents' Fears of Fumes Compel Closure of School Four Months Early." Well before anybody heard of the harmful effects of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) — much less that Saugus school children had been exposed to it — the Saugus Union School District had sold the school buildings and property on Bouquet Canyon Road to a developer who was going to (and did) turn it into a shopping center. The school was slated to close in June 1978. Why? It was no longer a practical location for a school. When it was built in 1908 (and totally rebuilt in 1938), the school sat in the heart of Saugus. But now, the population of Saugus had shifted north of Bouquet. In the words of a school district official (see below), "nobody lives near it." During the 1977-78 school year, only 23 of its 397 pupils lived within walking distance. Then BOOM! Late January 1978, the California Air Resources Board holds a hearing and announces to the world that there's this thing called vinyl chloride monomer, and that it can cause cancer — and maybe birth defects and genetic mutations, too — and that children might be more susceptible to health risks than adults ... and by the way the kids at Saugus Elementary have been sucking it in. It was all over the news. Picture parents with pitchforks. The Saugus School Board met within days of the shocking ARB announcement, on Wednesday evening, Feb. 1, 1978, and said forget June — the school will close within 48 hours. And it did. Friday afternoon, Feb. 3, 1978, the last child walked out the front door, never to return. So why not force the offending factory to close, instead? For one thing (as reported below), the school was going to close anyway in a few months. All of the pieces were in place and there was available classroom space at other district schools. It could be done quickly, it was happening anyway, and it was considered better than throwing 300 people out of work — especially since Keysor-Century was already set to spend $3.3 million in taxpayer money to install process controls including a VCM fume incinerator (which it did in late 1978). The modern reader might consider how little was known about pollutants at the time. Keysor-Century opened in Saugus in 1957 and operated the same way it always did until the early 1970s, when the first regulations kicked in. The original Clean Air Act passed in 1963, but it was limited in scope and there wasn't even an Environmental Protection Agency until 1970. In that year and in 1977 (and 1990) the Act was substantially overhauled as more was learned about pollutants that weren't previously recognized as pollutants. In fact, when the ARB issued its staff report about Keysor-Century in January 1978, there was an OSHA rule in place to limit worker exposure inside the plant, but there was no standard or regulatory limit on emissions into the outside air. It was a known carcinogen, but nobody knew (or agreed on) how much was too much. Were kids exposed to cancer-causing fumes? Yes. Have there been reports of early deaths and other ill effects in subsequent years? Yes. Did the school district or the public know about the problem before the school property was sold? No. The EPA has estimated (based on school district records) that from 1958, when Keysor-Century began producing polyvinyl chloride (PVC) 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, until 1978, when Saugus Elementary School closed, some 5,000 children were exposed to VCM. It was such a new phenomenon that many of those 5,000 children served as guinea pigs for scientific studies into the effects of VCM on children — because at a distance of 1,000 feet, Saugus Elementary was the closest school to a VCM-emitting factory in the United States, and it was the only school to close because of exposure to the fumes. And for other reasons.

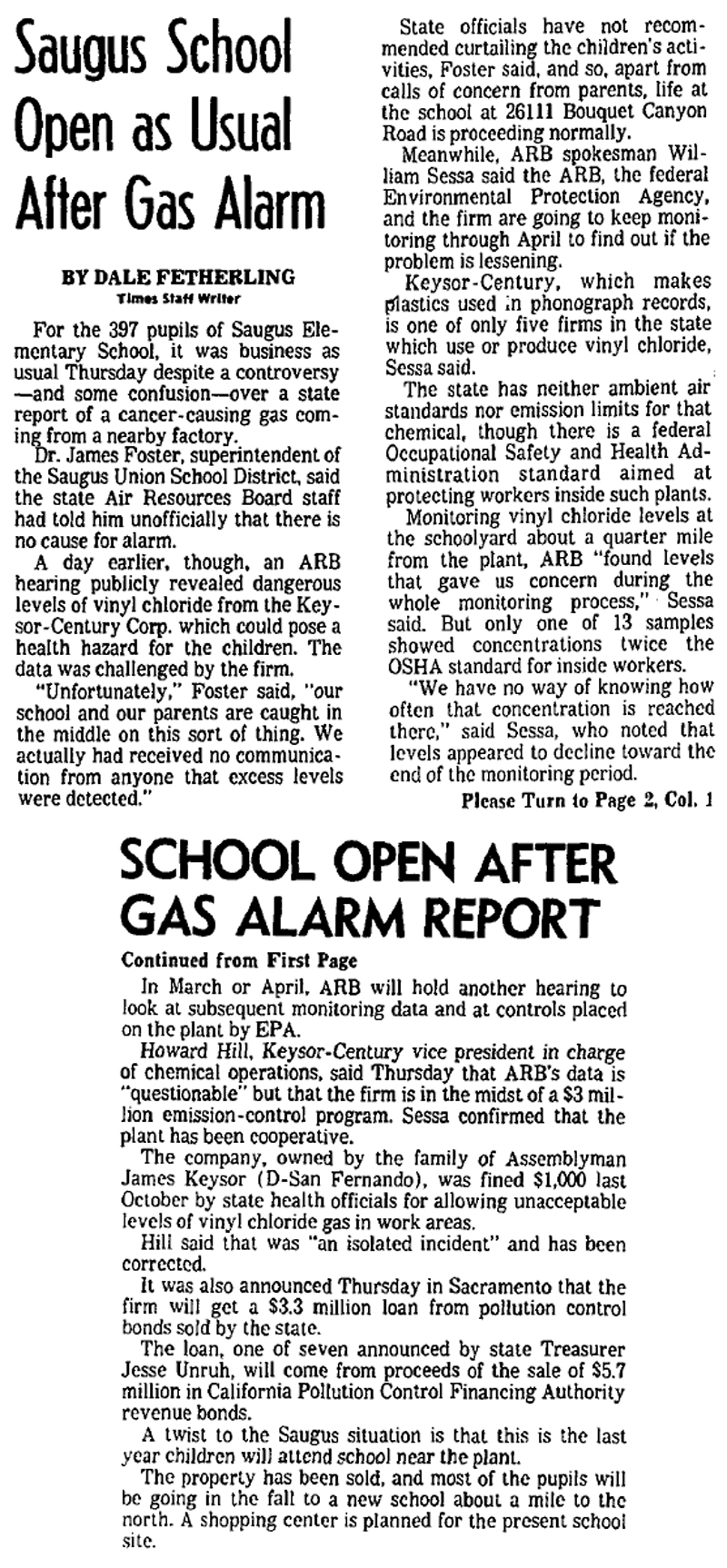

Saugus School Open as Usual After Gas Alarm. By Dale Fetherling, Times Staff Writer. Los Angeles Times | Friday, January 27, 1978.

For the 397 pupils of Saugus Elementary School, it was business as usual Thursday despite a controversy — and some confusion — over a state report of a cancer-causing gas coming from a nearby factory. Dr. James Foster, superintendent of the Saugus Union School District, said the state Air Resources Board staff had told him unofficially that there is no cause for alarm. A day earlier, though, an ARB hearing publicly revealed dangerous levels of vinyl chloride from the Keysor-Century Corp. which could pose a health hazard for the children. The data was challenged by the firm. "Unfortunately," Foster said, "our school and our parents are caught in the middle on this sort of thing. We actually had received no communication from anyone that excess levels were detected." State officials have not recommended curtailing the children's activities, Foster said, and so, apart from calls of concern from parents, life at the school at 26111 Bouquet Canyon Road is proceeding normally. Meanwhile, ARB spokesman William Sessa said the ARB, the federal Environmental Protection Agency, and the firm are going to keep monitoring through April to find out if the problem is lessening. Keysor-Century, which makes plastics used in phonograph records, is one of only five firms in the state which use or produce vinyl chloride, Sessa said. The state has neither ambient air standards or emission limits for that chemical, though there is a federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration standard aimed at protecting workers inside such plants. Monitoring vinyl chloride levels at the schoolyard about a quarter mile from the plant, ARB, "found levels that give us concern during the whole monitoring process," Sessa said. But only one of 13 samples showed concentrations twice the OSHA standard for inside workers. "We have no way of knowing how often that concentration is reached there," said Sessa, who noted that levels appeared to decline toward the end of the monitoring period. In March or April, ARB will hold another hearing to look at subsequent monitoring data and at controls placed on the plant by EPA. Howard Hill, Keysor-Century vice president in charge of chemical operations, said Thursday that ARB's data is "questionable" but that the firm is in the midst of a $3 million emission-control program. Sessa confirmed that the plant has been cooperative. The company, owned by the family of Assemblyman Jim Keysor (D-San Fernando), was fined $1,000 last October by state health officials for allowing unacceptable levels of vinyl chloride gas in work areas. Hill said that was "an isolated incident" and has been corrected. It was also announced Thursday in Sacramento that the firm will get a $3.3 million loan from pollution control bonds sold by the state. The loan, one of seven announced by state Treasurer Jesse Unruh, will come from proceeds of the sale of $5.7 million in California Pollution Control Financing Authority revenue bonds. A twist to the Saugus situation is that this is the last year children will attend school near the plant. The property has been sold, and most of the pupils will be going in the fall to a new school about a mile to the north. A shopping center is planned for the present school site. News story courtesy of Tricia Lemon Putnam.

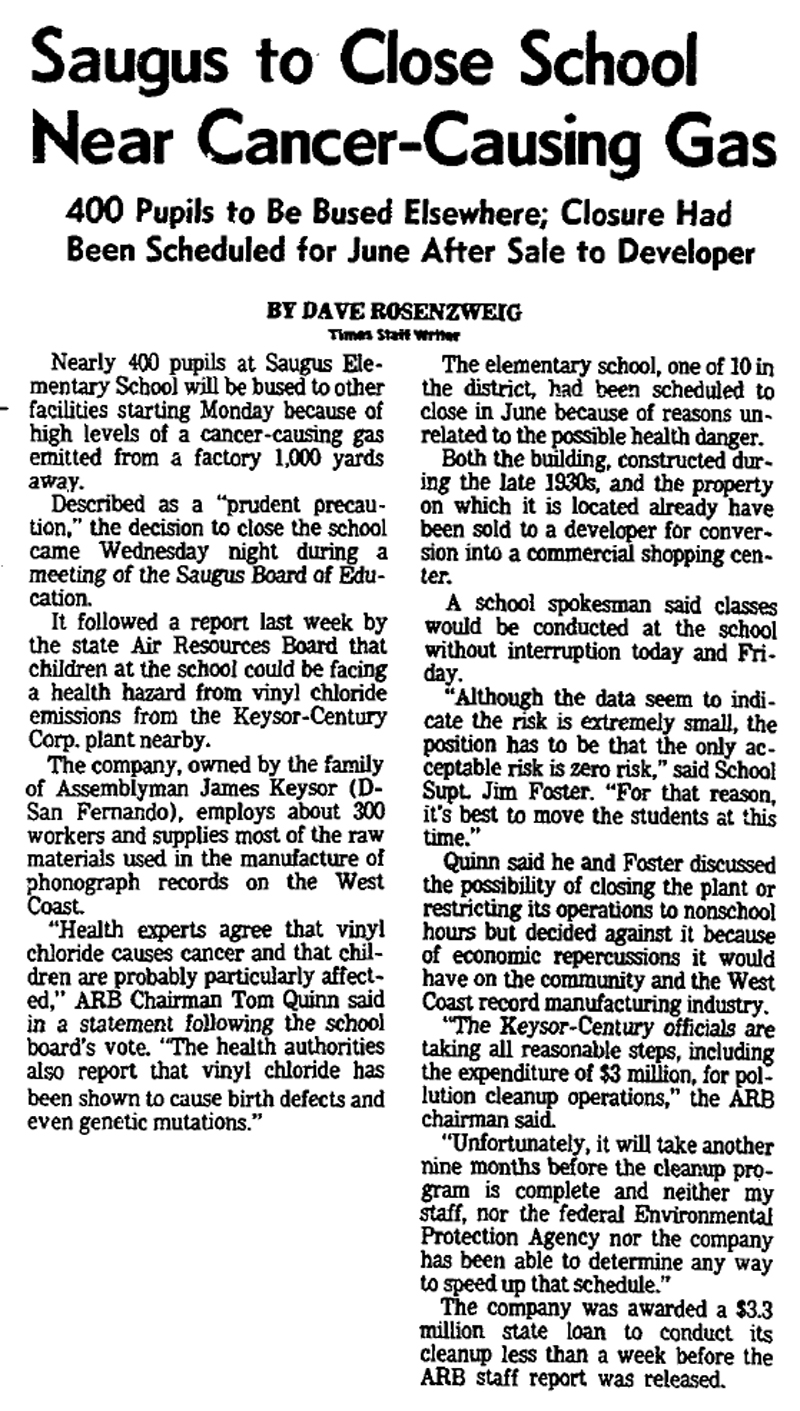

Saugus to Close School Near Cancer-Causing Gas. 400 Pupils to be Bused Elsewhere; Closure Had Been Scheduled for June After Sale to Developer. By Dave Rosenzweig, Times Staff Writer. Los Angeles Times | Thursday, February 2, 1978.

Nearly 400 pupils at Saugus Elementary School will be bused to other facilities starting Monday because of high levels of a cancer-causing gas emitted from a factory 1,000 yards away. Described as a "prudent precaution," the decision to close the school came Wednesday night during a meeting of the Saugus Board of Education. It followed a report last week by the state Air Resources Board that children at the school could be facing a health hazard from vinyl chloride emissions from the Keysor-Century Corp. plant nearby. The company, owned by the family of Assemblyman Jim Keysor (D-San Fernando), employs about 300 workers and supplies most of the raw materials used in the manufacture of phonograph records on the West Coast. "Health experts agree that vinyl chloride causes cancer and that children are probably particularly affected," ARB Chairman Tom Quinn said in a statement following the school board's vote. "The health authorities also report that vinyl chloride has been shown to cause birth defects and even genetic mutations." The elementary school, one of 10 in the district, had been scheduled to close in June because of reasons unrelated to the possible health danger. Both the building, constructed during the late 1930s, and the property on which it is located already have been sold to a developer for conversion into a commercial shopping center. A school spokesman said classes would be conducted at the school without interruption today and Friday. "Although the data seem to indicate the risk is extremely small, the position has to be that the only acceptable risk is zero risk," said School Supt. Jim Foster. "For that reason, it's best to move the students at this time." Quinn said he and Foster discussed the possibility of closing the plant or restricting its operations to non-school hours but decided against it because of economic repercussions it would have on the company and the West Coast record manufacturing industry. "The Keysor-Century officials are taking all reasonable steps, including the expenditure of $3 million, for pollution cleanup operations," the ARB chairman said. "Unfortunately, it will take another nine months before the cleanup program is complete and neither my staff, nor the federal Environmental Protection Agency nor the company has been able to determine any way to speed up that schedule." The company was awarded a $3.3 million state loan to conduct its cleanup less than a week before the ARB staff report was released. News story courtesy of Tricia Lemon Putnam.

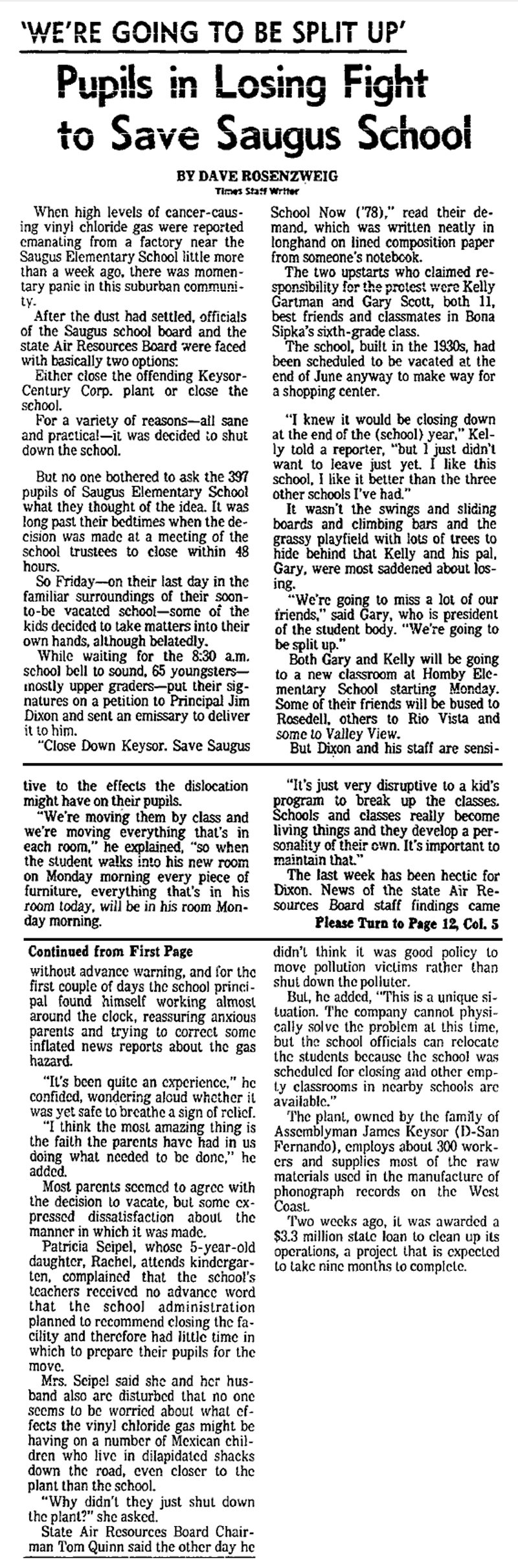

Pupils in Losing Fight to Save Saugus School. 'We're Going to Be Split Up'. By Dave Rosenzweig, Times Staff Writer. Los Angeles Times | Saturday, February 4, 1978.

When high levels of cancer-causing vinyl chloride gas were reported emanating from a factory near the Saugus Elementary School little more than a week ago, there was momentary panic in this suburban community. After the dust had settled, officials of the Saugus school board and the state Air Resources Board were faced with basically two options: Either close the offending Keysor-Century Corp. plant or close the school. For a variety of reasons — all sane and practical — it was decided to shut down the school. But no one bothered to ask the 397 pupils of Saugus Elementary School what they thought of the idea. It was long past their bedtimes when the decision was made at a meeting of the school trustees to close within 48 hours. So Friday — on their last day in the familiar surroundings of their soon-to-be vacated school — some of the kids decided to take matters into their own hands, although belatedly. While waiting for the 8:30 a.m. school bell to sound, 65 youngsters — mostly upper graders — put their signatures on a petition to Principal Jim Dixon and sent an emissary to deliver it to him. "Close Down Keysor. Save Saugus School Now ('78)," read their demand, which was written neatly in longhand on lined composition paper from someone's notebook. The two upstarts who claimed responsibility for the protest were Kelly Gartman and Gary Scott, both 11, best friends and classmates in Bona Sipka's sixth-grade class. The school, built in the 1930s, had been scheduled to be vacated at the end of June anyway to make way for a shopping center. "I knew it would be closing down at the end of the (school) year," Kelly told a reporter, "but I just didn't want to leave just yet. I like this school. I like it better than the three other schools I've had." It wasn't the swings and sliding boards and climbing bars and the grassy playfield with lots of trees to hide behind that Kelly and his pal, Gary, were most saddened about losing. "We're going to miss a lot of our friends," said Gary, who is president of the student body. "We're going to be split up." Both Gary and Kelly will be going to a new classroom at Homby [sic, s/b Honby] Elementary School starting Monday. Some of their friends will be bused to Rosedell, others to Rio Vista and some to Valley View. (Editor's note: The Honby school was transferred in 1991 to the Sulphur Springs Union School District and renamed Canyon Springs.) But Dixon and his staff are sensitive to the effects the dislocation might have on their pupils. "We're moving them by class and we're moving everything that's in each room," he explained, "so when the student walks into his new room on Monday morning every piece of furniture, everything that's in his room today, will be in his room Monday morning. "It's just very disruptive to a kid's program to break up the classes. Schools and classes really become living things and they develop a personality of their own. It's important to maintain that." The last week has been hectic for Dixon. News of the state Air Resources Board staff findings came without advance warning, and for the first couple of days the school principal found himself working almost around the clock, reassuring anxious parents and trying to correct some inflated news reports about the gas hazard. "It's been quite an experience," he confided, wondering aloud whether it was yet safe to breathe a sigh of relief. "I think the most amazing thing is the faith the parents have had in us doing what needed to be done," he added. Most parents seemed to agree with the decision to vacate, but some expressed dissatisfaction about the manner in which it was made. Patricia Seipel, whose 5-year-old daughter, Rachel, attends kindergarten, complained that the school's teachers received no advance word that the school administration planned to recommend closing the facility and therefore had little time in which to prepare their pupils for the move. Mrs. Seipel said she and her husband also are disturbed that no one seems to be worried about what effects the vinyl chloride gas might be having on a number of Mexican children who live in dilapidated shacks down the road, even closer to the plant than the school. "Why didn't they just shut down the plant?" she asked. State Air Resources Board Chairman Tom Quinn said the other day he didn't think it was good policy to move pollution victims rather than shut down the polluter. But, he added, "This is a unique situation. The company cannot physically solve the problem at this time, but the school officials can relocate the students because the school was scheduled for closing and other empty classrooms in nearby schools are available." The plant, owned by the family of Assemblyman James Keysor (D-San Fernando), employs about 300 workers and supplies most of the raw materials used in the manufacture of phonograph records on the West Coast. Two weeks ago, it was awarded a $3.3 million state loan to clean up its operations, a project that is expected to take nine months to complete. News story courtesy of Tricia Lemon Putnam.

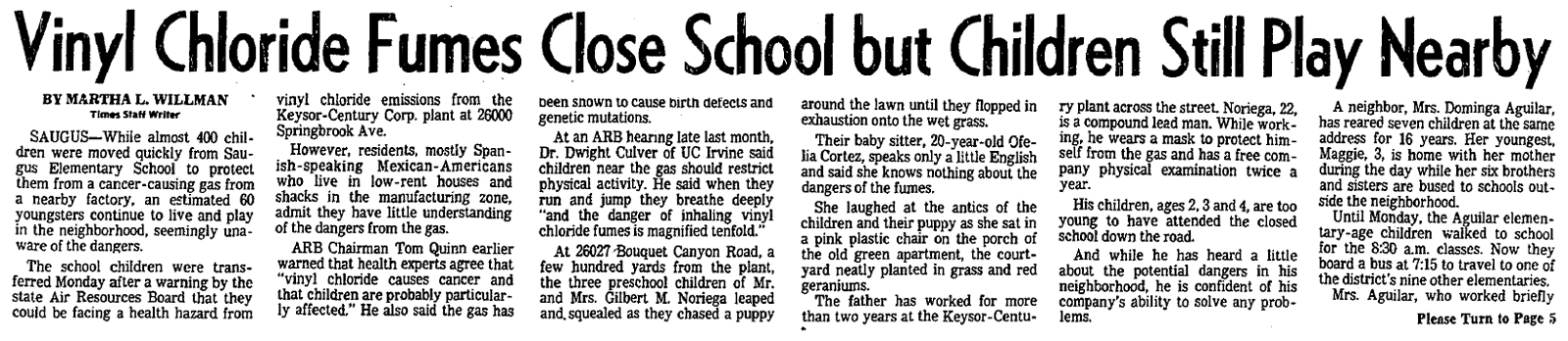

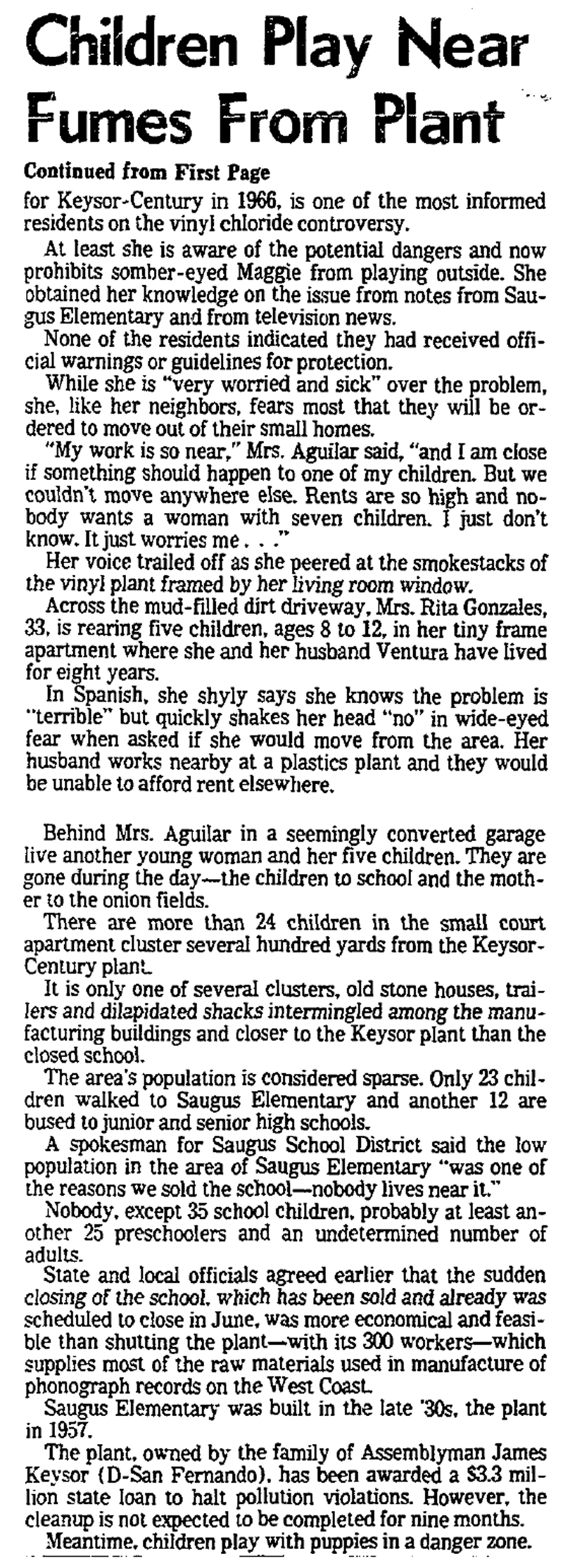

Vinyl Chloride Fumes Close School but Children Still Play Nearby. By Martha L. Willman, Times Staff Writer. Los Angeles Times | Thursday, February 9, 1978. Saugus — While almost 400 children were moved quickly from Saugus Elementary School to protect them from a cancer-causing gas from a nearby factory, an estimated 60 youngsters continue to live and play in the neighborhood, seemingly unaware of the dangers. The school children were transferred Monday after a warning by the state Air Resources Board that they could be facing a health hazard from vinyl chloride emissions from the Keysor-Century Corp. plant at 26000 Springbrook Ave. However, residents, mostly Spanish-speaking Mexican-Americans who live in low-rent houses and shacks in the manufacturing zone, admit they have little understanding of the dangers from the gas. ARB Chairman Tom Quinn earlier warned that health experts agree that "vinyl chloride causes cancer and that children are probably particularly affected." He also said the gas has been shown to cause birth defects and genetic mutations. At an ARB hearing late last month, Dr. Dwight Culver of UC Irvine said children near the gas should restrict physical activity. He said when they run and jump they breathe deeply "and the danger of inhaling vinyl chloride fumes is magnified tenfold." At 26027 Bouquet Canyon Road, a few hundred yards from the plant, the three preschool children of Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert M. Noriega leaped and squealed as they chased a puppy around the lawn until they flopped in exhaustion onto the wet grass. Their baby sitter, 20-year-old Ofelia Cortez, speaks only a little English and said she knows nothing about the dangers of the fumes. She laughed at the antics of the children and their puppy as she sat in a pink plastic chair on the porch of the old green apartment, the courtyard neatly planted in grass and red geraniums. The father has worked for more than two years at the Keysor-Century plant across the street. Noriega, 22, is a compound lead man. While working, he wears a mask to protect himself from the gas and has a free company physical examination twice a year. His children, ages 2, 3 and 4, are too young to have attended the closed school down the road. And while he has heard a little about the potential dangers in his neighborhood, he is confident of his company's ability to solve any problems. A neighbor, Mrs. Dominga Aguilar, has reared seven children at the same address for 16 years. Her youngest, Maggie, 3, is home with her mother during the day while her six brothers and sisters are bused to schools outside the neighborhood. Until Monday, the Aguilar elementary-age children walked to school for the 8:30 a.m. classes. Now they board a bus at 7:15 to travel to one of the district's nine other elementaries. Mrs. Aguilar, who worked briefly for Keysor-Century in 1966, is one of the most informed residents on the vinyl chloride controversy. At least she is aware of the potential dangers and now prohibits somber-eyed Maggie from playing outside. She obtained her knowledge on the issue from notes from Saugus Elementary and from television news. None of the residents indicated they had received official warnings or guidelines for protection. While she is "very worried and sick" over the problem, she, like her neighbors, fears most that they will be ordered to move out of their small homes. "My work is so near," Mrs. Aguilar said, "and I am close if something should happen to one of my children. But we couldn't move anywhere else. Rents are so high and nobody wants a woman with seven children. I just don't know. It worries me." Her voice trailed off as she peered at the smokestacks of the vinyl plant framed by her living room window. Across the mud-filled dirt driveway, Mrs. Rita Gonzales, 33, is rearing five children, ages 8 to 12, in her tiny frame apartment where she and her husband Ventura have lived for eight years. In Spanish, she shyly says she knows the problem is "terrible" but quickly shakes her head "no" in wide-eyed fear when asked if she would move from the area. Her husband works nearby at a plastics plant and they would be unable to afford rent elsewhere. Behind Mrs. Aguilar in a seemingly converted garage live another young woman and her five children. They are gone during the day — the children to school and the mother to the onion fields. There are more than 24 children in the small court apartment cluster several hundred yards from the Keysor-Century plant. It is only one of several clusters, old stone houses, trailer and dilapidated shacks intermingled among the manufacturing buildings and closer to the Keysor plant than the closed school. The area's population is considered sparse. Only 23 children walked to Saugus Elementary and another 12 are bused to junior and senior high schools. A spokesman for Saugus School District said the low population in the area of Saugus Elementary "was one of the reasons we sold the school — nobody lives near it." Nobody, except 35 school children, probably at least another 25 preschoolers and an undetermined number of adults. State and local officials agreed earlier that the sudden closing of the school, which had been sold and already was scheduled to close in June, was more economical and feasible than shutting the plant — with its 300 workers — which supplies most of the raw materials used in the manufacture of phonograph records on the West Coast. Saugus Elementary was built in the late 1930s, the plant in 1957. The plant, owned by the family of Assemblyman James Keysor (D-San Fernando), has been awarded a $3.3 million state loan to halt pollution violations. However, the cleanup is not expected to be completed for nine months. Meantime, children play with puppies in a danger zone. News story courtesy of Tricia Lemon Putnam.

|

Construction 1909-1910

Earliest 1910

Original 1910

Expansion

1936-38 Rebuild

Kindergarten 1956

SUSD Mystery Photos 1960s

Why Did Saugus School Close?

School Bell Through the Years

School Bell @SCVHS

• Protocol to Trace Saugus School Students Exposed to Vinyl Chloride (ARB 1984)

See Also:

Why Did Saugus School Close?

• Protocol to Trace Saugus School Students Exposed to Vinyl Chloride (ARB 1984)

~1986 • Bud Keysor Obituary 2000 • Keysor-Century Quits 2003 |

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.