|

|

St. Francis Dam Disaster

|

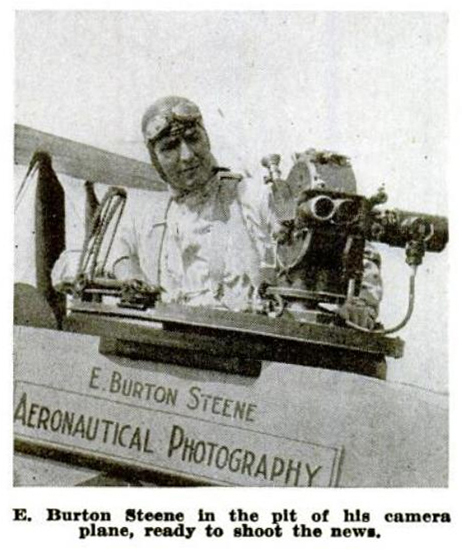

(Silent) Did someone give his life to get this film footage of the broken St. Francis Dam on March 13, 1928 — the morning after it failed? That's what a story in the August 1931 edition of Popular Aviation says (below). We don't know how accurate it is; we haven't heard of a plane crash, much less two of them, let alone a fatal one, in the vicinity of the dam disaster. That's not to say it didn't happen; there was a lot going on that day. It warrants further inquiry. According to the story, pilot Jim Barry and cinematographer E. Burton Steene were in a two-seat airplane getting aerial footage for Pathe Weekly News Reel Co. It says they were the first aviators on scene — except for a plane carrying newspaper men, which would make them second on scene. It's likely the first airplane was carrying George Watson, the L.A. Times staff photographer who shot the most famous next-day photo of the broken dam. (George Watson is the great-uncle of Signal newspaper photographer Dan Watson, who co-manages the important Watson Family Photographic Archive.) The Popular Aviation story describes the flood as if pilot Barry and cameraman Steene witnessed it in its early stages, which is curious since it struck in the dark of night. Nonetheless, one can see that Barry did pilot his craft fairly low to the ground, as described, enabling Steene to shoot the "tombstone" head-on (the section of the dam that remained standing). The story asserts Barry's plane was involved in a mid-air collision when another plane from a rival newsreel company showed up. Both planes' wings were damaged; the story says Barry provided assistance to the other pilot by maneuvering his own wing under the wing of the rival plane and lifting it out of canyon and onto a flat area where both planes ultimately crash-landed. Everyone survived except Barry, who reportedly succumbed to his injuries. This approx. 60-second version was shown on screens in Great Britain. It was released into the public domain by British Pathe in 2014. Filmed by Steene, it shows the tombstone, as well as receding floodwaters apparently just below the dam, and the empty (emptying) reservoir behind the dam. Title card reads: "America: Appalling Flood Disaster: 500 persons drowned ... damage estimated at seven million pounds ... as St. Francis Reservoir bursts, releasing 1,300,000,000 gallons of water." P.S.: For his part, Steene (c. 1885 - April 21, 1929) was a famous aerial photographer. He was an official photographer for the Army Air Corps during World War I, and according to the director[1], he shot most of the aerial footage in "Wings" (1927) despite being uncredited. 1. From "The Man and his Wings: William A. Wellman and the Making of the First Best Picture" by William Wellman Jr. (2006): "Wellman recalled, 'Burton Steene was the number one aerial photographer of the 20s and I grabbed him for Wings, the luckiest grab I ever made. He had a camera with an Akeley head, which means it had gears, a pan handle and a frightening whine to it as Burton panned up or down or from side to side. For 1926, it was unbelievable and Burton was so expert at it, he shot ninety percent of all the air scenes in Wings.'" (Courtesy of Stan Walker.)

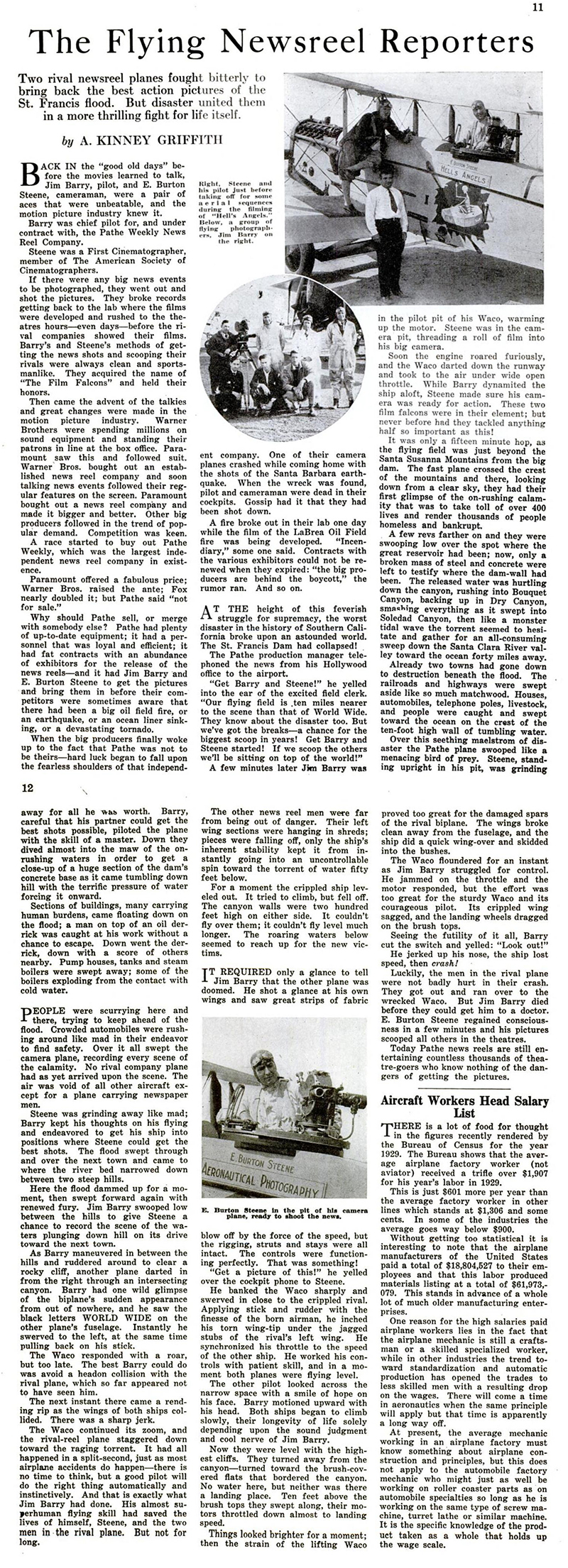

The Flying Newsreel Reporters. Two rival newsreel planes fought bitterly to bring back the best action pictures of the St. Francis flood. But disaster united them in a more thrilling fight for life itself. By A. Kinney Griffith. Popular Aviation | August 1931, pp. 11-12.

Barry was chief pilot for, and under contract with, the Pathe Weekly News Reel Company. Steene was a First Cinematographer, member of The America Society of Cinematographers. If there were any big news events to be photographed, they went out and shot the pictures. They broke record getting back to the lab where the films were developed and rushed to the theatres hours — even days — before the rival companies showed their films. Barry's and Steene's methods of getting the news shots and scooping their rivals were always clean and sportsmanlike. They acquired the name of "The Film Falcons" and held their honors. Then came the advent of the talkies and great changes were made in the motion picture industry. Warner Brothers [sic] were spending millions on sound equipment and standing their patrons in line at the box office. Paramount saw this and followed suit. Warner Bros. bought out an established news reel company and soon talking news events followed their regular features on the screen. Paramount bought out a news reel company and made it bigger and better. Other big producers followed in the trend of popular demand. Competition was keen. A race started to buy out Pathe Weekly, which was the largest independent news reel company in existence. Paramount offered a fabulous price; Warner Bros. raised the ante; Fox nearly doubled it; but Pathe said "not for sale." Why should Pathe sell, or merge with somebody else? Pathe had plenty of up-to-date equipment; it had a personnel that was loyal and efficient; it had fat contracts with an abundance of exhibitors for the release of the news reels — and it had Jim Barry and E. Burton Steene to get the pictures and bring them in before their competitors were sometimes aware that there had been a big oil field fire, or an earthquake, or an ocean liner sinking, or a devastating tornado. When the big producers finally woke up to the fact that Pathe was not to be theirs — hard luck began to fall upon the fearless shoulders of that independent company. One of their camera planes crashed while coming home with the shots of the [1925] Santa Barbara earthquake. When the wreck was found, pilot and cameraman were dead in their cockpits. Gossip had it that they had been shot down. A fire broke out in their lab one day while the film of the LaBrea Oil Field fire was being developed. "Incendiary," some one said. Contracts with the various exhibitors could not be renewed when they expired: "the big producers are behind the boycott," the rumor ran. And so on. At the height of this feverish struggle for supremacy, the worst disaster in the history of Southern California broke upon an astounded world. The St. Francis Dam had collapsed! The Pathe production manager telephoned the news from his Hollywood office to the airport. "Get Barry and Steene!" he yelled into the ear of the exited field clerk. "Our flying field is ten miles nearer to the scene that than of World Wide. They know about the disaster too. But we've got the breaks — a chance for the biggest scoop in years! Get Barry and Steene started! If we scoop the others we'll be sitting on top of the world!"

Soon the engine roared furiously, and the Waco darted down the runway and took to the air under wide open throttle. While Barry dynamited the ship aloft, Steene made sure his camera was ready for action. These two film falcons were in their element; but never before had they tackled anything half so important as this! It was only a fifteen minute hop, as the flying field was just beyond the Santa Susanna [sic] Mountains from the big dam. The fast plane crossed the crest of the mountains and there, looking down from a clear sky, they had their first glimpse of the on-rushing calamity that was to take toll of over 400 lives and render thousands of people homeless and bankrupt. A few revs farther on and they were swooping low over the spot where the great reservoir had been; now, only a broken mass of steel and concrete were left to testify where the dam-wall had been. The released water was hurtling down the canyon, rushing into Bouquet Canyon, backing up in Dry Canyon, smashing everything as it swept into Soledad Canyon, then like a monster tidal wave the torrent seemed to hesitate and gather for an all-consuming sweep down the Santa Clara River valley toward the ocean 40 miles away. Already two towns had gone down to destruction beneath the flood. The railroads and highways were swept aside like so much matchwood. Houses, automobiles, telephone poles, livestock, and people were caught and swept toward the ocean on the crest of the ten-foot high wall of tumbling water. Over this seething maelstrom of disaster the Pathe plane swooped like a menacing bird of prey. Steene, standing upright in his pit, was grinding away for all he was worth. Barry, careful that his partner could get the best shots possible, piloted the plane with the skill of a master. Down they dived almost into the maw of the onrushing waters in order to get a close-up of a huge section of the dam's concrete base as it came tumbling down hill with the terrific pressure of water forcing it onward. Sections of buildings, many carrying human burdens, came floating down on the flood; a man on top of an oil derrick was caught at his work without a chance to escape. Down went the derrick, down with a score of others nearby. Pump houses, tanks and steam boilers were swept away; some of the boilers exploding from the contact with the cold water. People were scurrying here and there, trying to keep ahead of the flood. Crowded automobiles were rushing around like mad in their endeavor to find safety. Over it all swept the camera plane, recording every scene of the calamity. No rival company plane had yet arrived upon the scene. The air was void of all other aircraft except for a plane carrying newspaper men. Steene was grinding away like mad; Barry kept his thoughts on his flying and endeavored to get his ship into positions where Steene could get the best shots. The flood swept through and over the next town and came to where the river bed narrowed down between two steep hills. Here the flood dammed up for a moment, then swept forward again with renewed fury. Jim Barry swooped low between the hills to give Steene a chance to record the scene of the waters plunging down hill on its drive toward the next town. As Barry maneuvered in between the hills and ruddered around to clear a rocky cliff, another plane darted in from the right through an intersecting canyon. Barry had one wild glimpse of the biplane's sudden appearance from out of nowhere, and he saw the black letters WORLD WIDE on the other plane's fuselage. Instantly he swerved to the left, at the same time pulling back on his stick. The Waco responded with a roar, but too late. The best Barry could do was aoivd a head-on collision with the rival plane, which so far appeared not to have seen him. The next instant there came a rending rip as the wings of both ships collided. There was a sharp jerk. The Waco continued its zoon, and the rival-reel plane staggered down toward the raging torrent. It had all happened in a split-second, just as most airplane accidents do happen — there is no time to think, but a good pilot will do the right thing automatically and instinctively. And that is exactly what Jim Barry had done. His almost superhuman flying skill had saved the lives of himself, Steene, and the two men in the rival plane. But not for long. The other news reel men were far from being out of danger. Their left wing sections were hanging in shreds; pieces were falling off, only the ship's inherent stability kept it from instantly going into an uncontrollable spin toward the torrent of water fifty feet below. For a moment the crippled ship leveled out. It tried to climb, but fell off. The canyon walls were two hundred feet high on either side. It couldn't fly over them; it couldn't fly level much longer. The roaring waters below seemed to reach up for the new victims. It required only a glance to tell Jim Barry that the other plane was doomed. He shot a glance at his own wings and saw great strips of fabric blow off by the force of the speed, but the rigging, struts and stays were all intact. The controls were functioning perfectly. That was something! "Get a picture of this!" he yelled over the cockpit phone to Steene. He banked the Waco sharply and swerved in close to the crippled rival. Applying stick and rudder with the finesse of the born airman, he inched his torn wing-tip under the jagged stubs of the rival's left wing. He synchronized his throttle to the speed of the other ship. He worked his controls with patient skill, and in a moment both planes were flying level. The other pilot looked across the narrow space with a smile of hope on his face. Barry motioned upward with his head. Both ships began to climb slowly, their longevity of life solely depending upon the sound judgment and cool nerve of Jim Barry. Now they were level with the highest cliffs. They turned away from the canyon — turned toward the brush-covered flats that bordered the canyon. No water here, but neither was there a landing place. Ten feet above the brush tops they swept along, their motors throttled down almost to landing speed. Things looked brighter for a moment; then the strain of the lifting Waco proved too great for the damaged spars of the rival biplane. The wings broke clean away from the fuselage, and the ship did a quick wing-over and skidded into the bushes. The Waco floundered for an instant as Jim Barry struggled for control. He jammed on the throttle and the motor responded, but the effort was too great for the sturdy Waco and its courageous pilot. Its crippled wing sagged, and the landing wheels dragged on the brush tops. Seeing the futility of it all, Barry cut the switch and yelled: "Look out!" He jerked up his nose, the ship lost speed, then crash! Luckily the men in the rival plane were not badly hurt in their crash. They got out and ran over to the wrecked Waco. But Jim Barry died before they could get him to a doctor. E. Burton Steene regained consciousness in a few minutes and his pictures scooped all others in the theatres. Today Pathe news reels are still entertaining countless thousands of theatre-goers who know nothing of the dangers of getting the pictures. Story courtesy of Stan Walker.

British Pathé releases 85,000 films on YouTube British Pathé Archive, April 17, 2014 — Newsreel archive British Pathé has uploaded its entire collection of 85,000 historic films, in high resolution, to its YouTube channel. This unprecedented release of vintage news reports and cinemagazines is part of a drive to make the archive more accessible to viewers all over the world. "Our hope is that everyone, everywhere who has a computer will see these films and enjoy them," says Alastair White, General Manager of British Pathé. "This archive is a treasure trove unrivalled in historical and cultural significance that should never be forgotten. Uploading the films to YouTube seemed like the best way to make sure of that." British Pathé was once a dominant feature of the British cinema experience, renowned for first-class reporting and an informative yet uniquely entertaining style. It is now considered to be the finest newsreel archive in existence. Spanning the years from 1896 to 1976, the collection includes footage — not only from Britain, but from around the globe — of major events, famous faces, fashion trends, travel, sport and culture. The archive is particularly strong in its coverage of the First and Second World Wars. Alastair White continues: "Whether you're looking for coverage of the Royal Family, the Titanic, the destruction of the Hindenburg, or quirky stories about British pastimes, it'll be there on our channel. You can lose yourself for hours." This project is being managed by German company Mediakraft, which has been responsible for numerous past YouTube successes. The company will be creating new content using British Pathé material, in English and in foreign languages.

Construction on the 600-foot-long, 185-foot-high St. Francis Dam started in August 1924. With a 12.5-billion-gallon capacity, the reservoir began to fill with water on March 1, 1926. It was completed two months later. At 11:57:30 p.m. on March 12, 1928, the dam failed, sending a 180-foot-high wall of water crashing down San Francisquito Canyon. An estimated 411 people lay dead by the time the floodwaters reached the Pacific Ocean south of Ventura 5½ hours later. It was the second-worst disaster in California history, after the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906, in terms of lives lost — and America's worst civil engineering failure of the 20th Century.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.