|

|

Eyewitness to the 20th Century

Katherine Hyde, Castaic Activist.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Sunday, December 2, 1984.

|

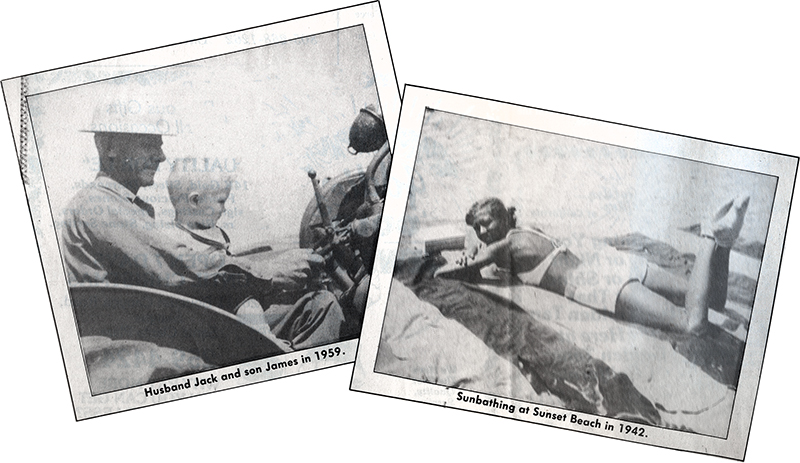

Katherine Hyde feels she has made an important contribution to her community. For some 25 years, she and a number of other concerned Castaic residents fought long and hard against a move to unify their school with the Hart school district. Eventually, she was the chairman of a grassroots committee organized to fight off unificiation. It was only a few years ago that Castaic school was finally secure as its own separate district. "To me, the bigger the school district, the less education for the children," she said recently. "I am firmly convinced that had we not gone to bat for Castaic, it probably would have been unified in '65. "I consider my biggest contribution was keeping Castaic school for Castaic." Katherine, who is now 71, lives just north of Castaic on a ranch nestled in the hills off Templin Highway. She lives alone on the isolated ranch — except, that is, for her 22 Great Danes. For years she operated a kennel here, but an accident (she was thrown off a horse two years ago) has forced her into temporary retirement. * * * Katherine Elizabeth James — along with a twin brother — was born in Los Angeles on August 13, 1913. Her first home was "in a little place called Douglas Street which is now under the Bunker Towers. Now you might say it was downtown, but in those days it was out in the sticks." The family then moved to Hollywood, which "was really out in the sticks," she said. Her father was a drummer from Kansas who came out to California with a traveling show, and never left. "Dad had only heard about California. He said they left snow 'rear deep to a small Indian,' and when they got off the train here there was sunlight, and the sunshine was warm. And he said, 'I have arrived.'" He gave up music for photography and eventually started a very lucrative photofinishing business. Although too young for World War I to have had any impact, she does have one particular childhood memory of it. "I can remember the day the war ended. I guess we had one of the few radios in the area. ... I don't know how my parents found out about it, but they heard it over this cat-whisker crystal set that we had. "So, my brother said we ought to celebrate. So we all got big wash-pans and boards and we formed a procession and we went through the neighborhood banging the wash-pans and hollering that the war was over. And the neighbors all came running out." Katherine and her brother attended a private "prep school" for preschoolers where they were taught reading and writing, etiquette and even French. At 6, when the two of them were ready to enter public school, they tested at fourth grade level and were placed in the third grade. That made things difficult for Katherine as she got older. "I was 15 and a senior. All the other girls were dating, but my mother just said 'Dear, you're too young.'" All three of the James children attended Polytechnic High School in Los Angeles. Her oldest brother studied aeronautics while Katherine and her twin took up engineering. After high school she worked in her father's business, then continued studying engineering at UCLA — after a brief diversion. "Actually I was going to be a baby doctor. ... I was pre-med my first year. My professor called me in and he said, 'Miss James, I want to talk to you.' He said, 'What do you plan to do as a baby doctor?' And I said, 'Well, I don't know. What do baby doctors do? They give birth to babies, don't they?' And he said — and of course abortion was a felony at that time — and he said, 'What would you do if a 13- or 14-year-old girl got pregnant and came to you for an abortion?' "I said 'Well, I'd abort her of course,'" she laughed. "And he said, 'Well, I thought you would.' "I don't believe in babies having babies. I think mature people ought to have babies. I think that any woman who does not wish to have a child should not be forced to have a child. And I think that the problem that we have with our abused children and with the horrible things that people do to kids, stems from the fact that they really didn't want them. Because if you wanted a child, you'd take care of it. "I am very much pro-abortion. I think these, what d'ya call them, these lifer groups, are really not looking at the situation. I think that they're letting their religious ideas overshadow what is actually the fact. And I probably had the same ideas then." Her professor told her she could not remain in his class with "those ideas" and told her she would have problems if she pursued a career in medicine. He suggested she return to engineering, and she did. In those days, few women studied medicine; fewer still chose a career in engineering. "There were maybe two other women (in the school of engineering)," she recalled. "But I sure did have a spread of men." The family's wealth not only shielded them from the effects of the Depression, but — at least for Katherine — sheltered her from even the knowledge that many people here and abroad were destitute, even starving. "We never had any Depression in our family. My father was a very wealthy man. We had two cars and nobody else in the three blocks around us had any. "I never even realized that there was anybody in need. It just never occurred to me. We had everything that we wanted. Oh, we had a beach cottage and we had boats, you know, we had everything." But she still remembers the incident that finally opened her eyes. Her father had some business to take care of downtown on Spring Street. He parked in an alley behind a restaurant, and Katherine waited in the car with her aunt. After a short time, she told her aunt she could feel that there were people around. "Of course it was dark, and you couldn't see anything. We had been there maybe another five minutes when the back door of the cafeteria opened up, and out came six men (each with) a great big garbage can. "They opened them up and they set them in a row outside the cafeteria. Then they went back and closed the door. But they turned a light on when they came out. And the minute the door closed, there came a whole shmear of people, maybe 50 or 60. Just a crowd of people. And I said, 'God Aunt Ellie, look. I told you there were people around here.' And those people were going through those cans of food and each one of them had ... shopping bags with handles ... and every one of them was picking out some of this food and putting it into these sacks. "And I said to my aunt in horror, 'What are they doing?' And my aunt said 'Well, it looks like they're going through the garbage.' And I said, 'Well, what do you suppose they're going to do with it?' And she said, 'Well, I imagine they're going to take it home and eat it.' "And I said, 'Oh, surely not garbage.' And that was the first time I was aware that there were poor people in the world. Which, I know, sounds absolutely insane." She asked her mother what could be done about these hungry people but was basically told that life is not fair. "I guess right then is when I decided now is the time to go on my crusade to help people. Until that time I was living in a Utopia, I guess. "I started buying food for anyone who looked liked they needed it." And she invited friends who had no place to go for vacation to the family's beach cottage near what is now Seal Beach. In college, she bought books for students who could not afford them. She had jobs following graduation, but none was in engineering. "There weren't many jobs for women in that field then. But I think education helps, no matter what." She worked at a Los Angeles radio station as a scriptwriter for a while, then went back to photofinishing and became manager of a film lab. She also started a kennel. Katherine had always dreamed of owning a harlequin Great Dane. She remembers being 10 years old and seeing a picture of one on a fashion plate and wanting one ever since. "I saw I couldn't afford to buy one, so that's how I got into (the kennel business)." Although the dogs were rare on the West Coast, she found a woman who sold her a well-bred female for just $35 (they usually went for $150). She then located a prominent doctor whose Dane was an international champion. The doctor's wife's name was Sigrid, so Katherine registered her dog under that name, then called the doctor and asked him if he would like to breed his dog with his wife's namesake. "It tickled him so. He didn't charge me and took a puppy instead. I really lucked out." She started her first kennel while living in Burbank, then moved to Van Nuys. "At that time (Burbank) was kind of an agricultural community. Then they changed the laws to limit the number of dogs you could have. So, Van Nuys was a little more rural," she laughed. "God, looking back... "Then the war came and, at first, you couldn't give dogs away. Nobody would buy anything. So, I carried through the war just my best breeding stock. "The rest were given to the Army as guard dogs, used for patroling. One was even sent to Guadalcanal — or Iwo Jima — and was given an honorable discharge and a medal." * * * With the war came new opportunities: Women were needed in the work force and Katherine, who landed a defense job with Lockheed, finally had a chance to use her engineering background. She also got married. She met Jack years before, in 1933 during a trip to Salt Lake City with her mother. He was a friend of a friend, "so I was a blind date from California," she said of that first meeting. They kept in touch for years afterward. And when just after Pearl Harbor Katherine learned he had enlisted and was sent to Los Angeles for training, she contacted him. A commando for the Marines, he married her the following year while on leave. She was managing a photo lab when Lockheed hired her. "It was a defense job, and I didn't think it was going to last. So I kept both." On holding down two jobs, she said: "That's the way to get along in life. You have to work hard. Anyway, I was ambitious in those days. A lot more ambitious than I am now." Eventually, she gave up the lab job and attended night school at USC to learn aeronautical engineering for her job. She started out in the electrical department, then moved on to writing maintenance manuals for the bombers. She had very few female co-workers. "Lockheed was really kind of a chauvinistic business. They really didn't like the idea of having women in the factory, because women were problems," she said. With an obviously female name, she was told to sign "all of my writing and all of my blueprints and all of my designs 'K. Hyde,' so nobody would know that I was a female." And it worked. "One day I'm sitting there at my desk when in marches about five of the Navy bigshots, with the gold epaulettes on the shoulders and the bars and hats, the whole shmear. "They came down the aisle and stopped right opposite my desk. And I'm sitting there thinking, 'Had you better dive under your desk, dear?' And Mr. Lundgren (the supervisor) says, 'I want you to meet — I don't recall what his name was, commander somebody. "And so I says, 'Hi.' And he said, 'My God, you're a woman. And I said, 'I hope so, sir.'" She was given a citation commending her for one of the maintenance chapters she had written and which they turned into a training film. "I was tickled to death," she said. But a week later, her supervisor took the citation back, gave it to the company president, and she never saw it again. The one time she said she felt actually discriminated against because she was a woman was over salary. She had been on the job for some time and had yet to receive her automatic raise. After receiving the citation, she went to her supervisor and demanded to know what was going on. "I figured I was worth a little more money." She was told she couldn't have any more raises because that would make her part of the company's engineering fraternity. "I said, 'Big deal. I'm here for the money. You either get me the money, or get me in some place where I do get the money." That's when she was moved to the manufacturing division. "That was the only time that I felt I'd been had. "I don't think there are barriers in any job (for women) like there used to be. I think if you've got it between the ears and you've got the education and you apply yourself, you can do anything. "But there are certain things a woman is not qualified to do. Like heavy, physical labor. Of course, I've always felt that a woman was intellectually superior. Definitely. If you can't be physically superior, you can be intellectually superior. "I'm not for ERA. I absolutely think that if ERA was to pass, the women of this country would be the biggest jackasses, just to allow it to happen. ... You can get just as far on your own as you could if ERA was pushing you. And if ERA should pass, you would be drafted right along with the men. There would be absolutely nothing you could do to save yourself from anything." At Lockheed, she also learned to fly and co-piloted a number of test flights. She was asked to join the WACs but declined. She said she never had any conflicts about working on bombers. "I never had any qualms about building the planes for the military because I figured the faster we got them out, the faster I'd get my husband home. That's what was in my mind. So, it didn't bother me at all." * * * Toward the end of the war, the dog breeding business picked up; by the end she had about 265 dogs and began looking for a bigger place. She and Jack were also looking to start a dairy, and their search for more land led them north to the Santa Clarita Valley. "I remember everything this side (north) of Lyons was alfalfa," she said, "and everywhere we looked the Realtor would tell us the property belonged to Newhall Land & Farming. We drove for miles — it all belonged to Newhall Land." They finally settled on a ranch situated on about 120 acres off of Templin Highway. She said it was the homestead of one of the Atwoods' (who owned Paradise Ranch) daughters. They moved there in 1890, and it was finally sold in 1940 to a movie stuntman by the name of Rocky Cameron. The Hydes bought the ranch in 1945, about the same time she was laid off by Lockheed. They never started a dairy, but they moved the kennel there, brought up a few horses and raised cattle. "Castaic in those days was a grocery store, a post office, two service stations and a garage. There were very few houses. As I recall, U.S. 99 just went right through town and right on up the hill. "Newhall was a little burg. It was tiny. San Fernando Road, from the park to Lyons Avenue, is about all that was here. And if you look at it now, it really has changed. Saugus was the Saugus Cafe — that and the train station across the street. That was Saugus." Katherine said she remembers seeing Newhall Land and Farming's "drawing board" of Valencia at a presentation at Hart High some 35 years ago. "I really had an insight as to what was going to be at that time. And they've been very faithful about doing exactly what they said they were going to do." Her husband filed on a mining claim in Trona, near Ridgecrest. He was also hired as a geologist by Kerr-McGee's nearby plant. The money was so good, they bought a house there and commuted between their two homes. Katherine grew accustomed to living alone at the isolated ranch. Her son James was born in 1956. The many changes she has seen excite her, but many more just make her angry. "I was thoroughly intrigued with the retrieval of the two satellites. I listened to the whole thing over the radio, and I thought that was just great. Now we can sneak out and snatch the Russian satellites," she said laughing. "They ought to hire me to figure out how we can do things. "I guess the computer age was just starting then (when she worked at Lockheed). They were just barely beginning to use that technology. I don't think at the time they realized the potential." On the advances in medicine, she said: "If you can maintain the quality of life, it's great. But come the time that you're a total basket case and you're only being kept alive on a support system, I think legally you should be able to say if you want to go or not. "Economic changes probably bother me as much as any — this bit of the government going on deficit spending and doing nothing about correcting it." She said she would like to see every working person turn in a dollar to a volunteer agency each month to reduce the deficit. "But I guess that's living in a Utopia."

This is the fourth biographical profile of The Signal's series of "Eyewitness To The 20th Century." The series continues Wednesday.

Download individual pages here. Clipping courtesy of Cynthia Neal-Harris, 2019.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.