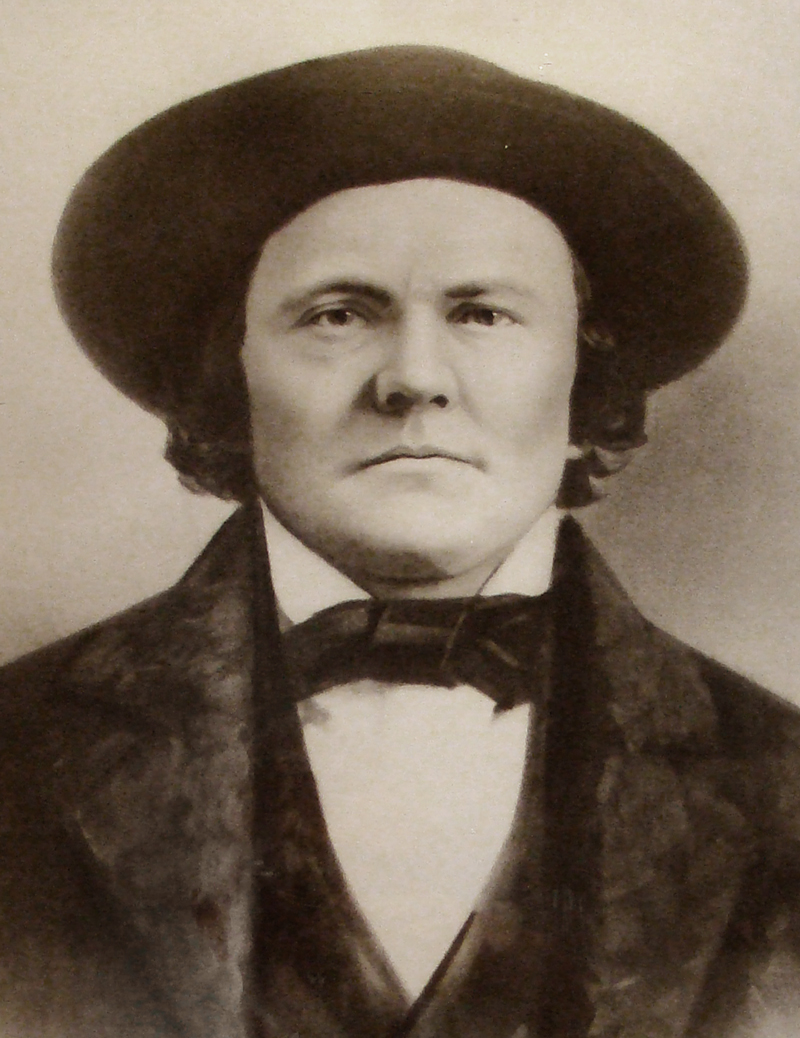

An iconic figure of the Old West played a key role in a local battle alongside the legendary Edward F. "Ned" Beale during the Mexican War in 1846.

Kit Carson was best known for his contributions to American history as a mountain man, trapper, scout, Indian agent and fighter, and guide for the famous trailblazing Western expeditions led by John C. Fremont. But he is also known for his heroic actions as he and Beale saved American forces from imminent slaughter during the Battle of San Pasqual in Southern California.

Carson the Trapper

Born in Kentucky in 1809, Kit Carson spent his early years near Franklin, Mo., at the Eastern end of the Santa Fe Trail. Following his father's death, Carson, at age 14, dropped out of school and went to work for a saddle shop in Franklin. Two years later, after hearing tales of the Far West from the trappers and traders who frequented his workplace, he left the saddle business and joined a merchant caravan heading for Santa Fe.

In 1826 he took up residence with trapper and explorer Matthew Kinkead in Taos, N.M. During his time in Taos, he learned the skills of a trapper and became fluent in Spanish and seven Indian languages.

Using Taos as a base camp between 1829 and 1840, Carson roamed the West as a fur trapper and mountain man. He met his first wife, an Arapaho woman who went by the name of Singing Grass, at a mountain-man rendezvous along the Green River in Wyoming in 1835. Accompanied by Singing Grass, Carson worked for the Hudson Bay Co. and for the famed frontiersman Jim Bridger as he trapped beaver throughout what is now Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming and Montana. As the fur trade dwindled, Carson attended the last rendezvous at Fort Bridger near the Green River in 1840.

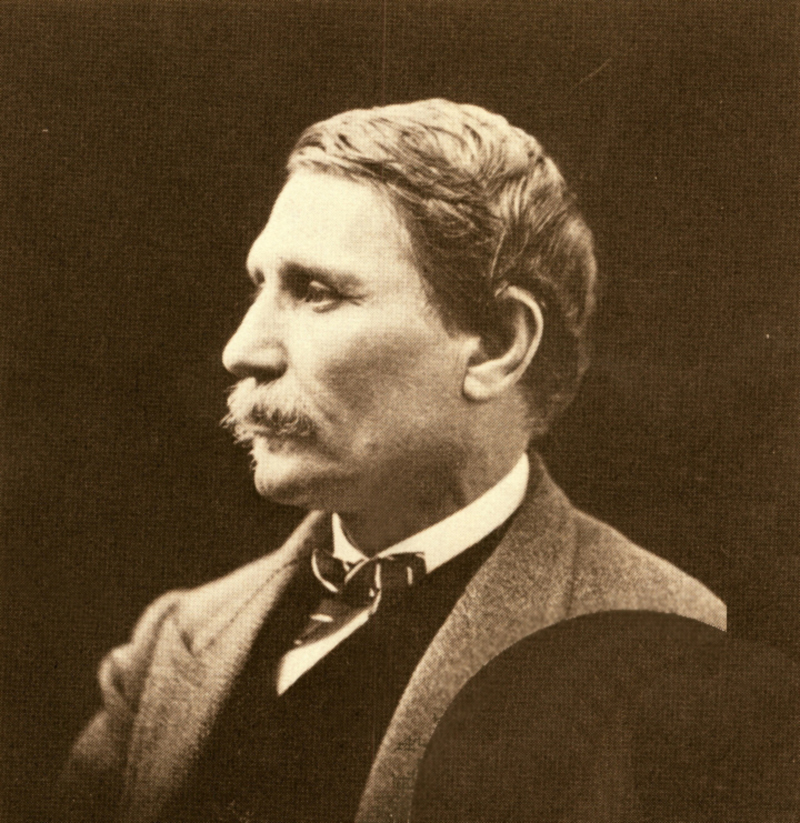

Carson and the Fremont Expeditions

Returning to Missouri in 1842, Carson had a chance meeting with the future Pathfinder, John C. Fremont, on a steamboat on the Missouri River. Fremont eventually hired him as a guide on his first Western expedition to South Pass in the Rocky Mountains in present-day Wyoming.

Kit Carson's living room in Taos. Now a house museum.

|

Fremont's expedition was an enormous success. After his report to Congress was published, the great migration of wagon trains began heading west along the Oregon Trail. Carson accompanied Fremont as a guide on his famous second and third expeditions to survey the Great Salt Lake in Utah and farther west to Fort Vancouver in the Pacific Northwest in 1843 and Oregon and California in 1845.

Fremont's report to Congress on the first expedition highlighted the exploits of Carson and turned him into a national legend. He became one of the most famous of the mountain men and was featured in many a Western dime novel.

While the goal of Fremont's third expedition in 1845 was initially to map the source of the Arkansas River, Fremont inexplicably headed straight for the Sacramento Valley in California where he proceeded to encourage American settlers to start a war with Mexico. After nearly provoking a battle with a Mexican general near Monterey, Fremont, Carson and their companions took refuge at Klamath Lake in Oregon. They eventually returned to the Sacramento Valley where they provoked the Bear Flag Revolt against the Mexicans.

John C. Fremont. Click for more.

|

Carson and the Mexican War

The Mexican-American War began in April 1846. Three months later, Fremont's men, now referred to as the California Battalion, met up with U.S. Commodore Robert Stockton in Monterey. There Stockton and Fremont joined forces with the intention of conquering Los Angeles and San Diego before heading on to Mexico City.

Carson's military career began there as he became a lieutenant for Stockton. Fremont's troops took San Diego without resistance in July 1846. After taking Santa Barbara, Stockton joined Fremont in San Diego, and together they marched to Los Angeles and captured the pueblo without resistance.

Fremont and Stockton asked Carson to convey the news of their California conquest to President James K. Polk. On his way to the nation's capital, Carson by chance met up with Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West at the deserted village of Valverde in present-day New Mexico.

Kearny's troops had taken over Santa Fe and conquered New Mexico in August 1846. They were marching west with the intention of conquering California, as well.

Learning from Carson that the conquest of California had already taken place, Kearny sent most of his troops back toward the East and, asserting superior authority, directed Carson to guide him and 100 remaining men back to California where he hoped to stabilize the military situation.

Carson guided Kearny's dragoons into California and arrived within 25 miles of San Diego in December 1846. Here they learned from a captured Mexican courier that a revolt had led to the Mexicans retaking California from Stockton except for San Diego, where Stockton's troops were under siege. Between Kearny's and Stockton's forces was the village of San Pasqual.

Kearny learned that Mexican Gen. Andres Pico was camped at San Pasqual with several hundred dragoons. He made the fateful decision to raid Pico's encampment in order to obtain fresh horses for his men.

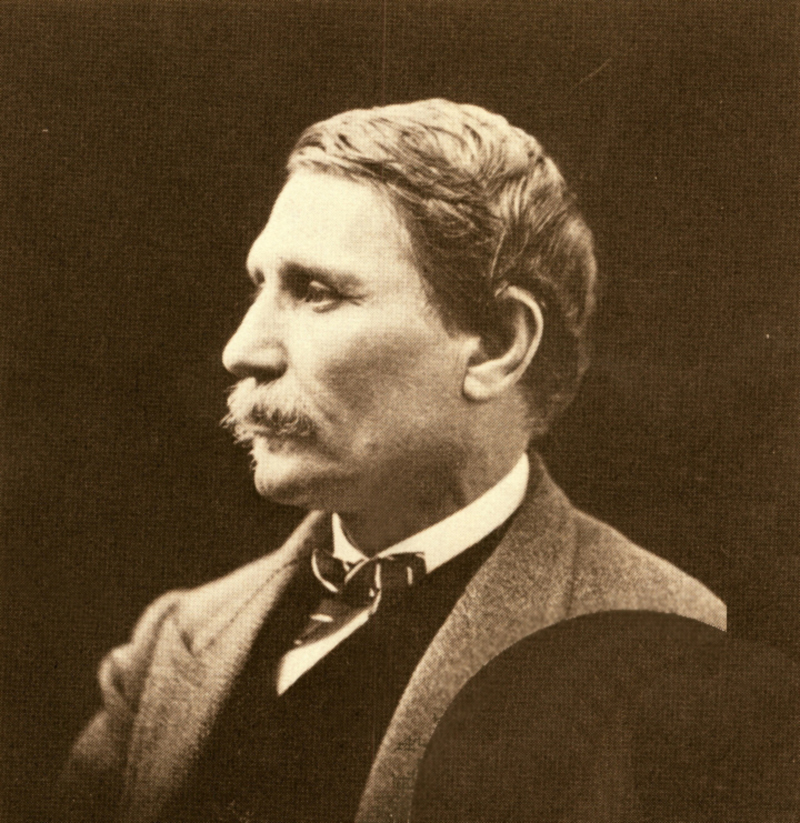

Edward F. Beale. Click for more.

|

Carson and Beale at San Pasqual

The Battle of San Pasqual began in the early morning hours of Dec. 6, 1846. It would turn out to be the bloodiest battle of the Mexican War in California. When it was over, at least 19 Americans and possibly six Mexicans would lose their lives.

Although outnumbered by the Americans, Pico's men quickly obtained the upper hand in battle. The troops under Kearny's command were low on supplies and weakened from their long, 2,000 mile march from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. By Dec. 8, it was clear that without further help, the Americans faced possible annihilation.

That evening, under cover of darkness, Kearny sent a young Navy lieutenant, Edward F. Beale, along with Kit Carson and an Indian guide to sneak through the Mexican lines and carry dispatches to Commodore Stockton 28 miles away in San Diego, seeking troop reinforcements.

Just a year earlier, Beale, who graduated from the Naval School in Philadelphia in 1842, had been assigned to Stockton's squadron. When the Mexican War began, Beale sailed with Stockton to San Diego where he was assigned to serve with the land forces. Beale and a small body of men under Lt. Archibald Gillespie joined Gen. Kearny's column just prior to the Battle of San Pasqual.

In order to avoid alerting the Mexican troops as they passed through, Carson and Beale abandoned their canteens and boots and proceeding barefoot through desert, rock and cactus. Through the first mile of their trek, they crawled on their bellies within 20 yards of Mexican sentries. They successfully made their way to San Diego where they alerted Stockton to the dire situation at San Pasqual.

Corner of the table upon which the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed. The whole table is on display at the L.A. County Natural History Museum. Click for more.

|

Believing all hope was gone, Kearny was relieved to see the arrival of 200 American troops sent from San Diego on Dec. 10. Now greatly outnumbering the Mexicans, the tide of the battle turned in the Americans' favor. Mexican forces withdrew and dispersed. Kearny made his way to San Diego by Dec. 12, and the reconquest of California was set in motion.

By January, it was all over. Fremont met up with Pico at Campo de Cahuenga in the San Fernando Valley where he accepted Pico's surrender on Jan. 13, 1847, and signed the Treaty of Cahuenga, ending the war between Mexico and the United States in California. Beale and Carson were recognized as heroes of the Battle of San Pasqual.

Ironically, Beale and Pico would later team up as partners to buy up oil claims in the Santa Clarita Valley in the 1860s, participating in the dawn of the California oil industry. It was Pico who was first commissioned to deepen a cut through the San Gabriel Mountains to allow for easier passage between the San Fernando and Santa Clarita valleys. Failing in this endeavor, the torch was passed to Beale, who completed the famous Beale's Cut in 1864.

Carson and the Indian Wars

As for Kit Carson, after the war ended, he returned to New Mexico to become a rancher. He was appointed Indian agent for the Ute and Jicarilla Apaches at Taos in 1854. He served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Although he organized New Mexico infantry volunteers at the Battle of Valverde in 1862, he spent most of the Civil War waging a brutal economic battle in an attempt to relocate the Navajo Indians.

To his credit, Carson was appalled by the belligerent attitude of his commander, Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton, toward the Navajos, and attempted to resign his post in 1863. Carleton, however, refused the resignation and coerced Carson into continuing the campaign against the tribe.

Eventually weakened by warfare with Carson and enemy tribes such as the Ute, Pueblo, Hopi and Zuni, the Navajos surrendered to Carson in 1864. They were forced to relocate by walking nearly 300 miles from Fort Canby, Ariz., to Fort Sumner, N.M. Involving 8,000 Navajo men, women and children, it became known as the "Long Walk." Hundreds of Navajos lost their lives during the difficult trek to Fort Sumner.

Kit Carson is buried in the family plot near his home in Taos, now a state park.

|

Carleton also sent Carson to deal with the Indians of West Texas in 1864. A combined force of Kiowa, Comanche and Plains Apache actually defeated Carson's forces at the Battle of Adobe Walls in November 1864. In spite of the defeat, Carson was credited with his wise decision to withdraw his troops when faced with a numerically superior Indian army.

After the Civil War, Carson was appointed a brigadier general, returned to the ranching business and moved to Colorado, where he took command of Fort Garland. During his stint at the fort, he was able to negotiate a peace treaty with the Utes.

But his health was failing, and he resigned his post the following year. Carson died of a ruptured aortic aneurysm at Fort Lyons, Colo., on May 23, 1868. His remains were taken for burial near his old home at Taos. There, his grave can be visited at Kit Carson Memorial State Park.