L.A. Times photo.

|

No one disputes that Norman M. Melrose gunned down William H. Broome on the streets of Acton in the late afternoon of Jan. 20, 1903.

What did become wildly controversial was Melrose's claim of self-defense to explain his actions.

As was explored last time, Melrose and Broome had been engaged in a long-running feud that began when Melrose accused Broome of being a swindler and bunco man who sold people worthless oil stock and land as founder of the Actonoma Oil and Mineral Development Co., which he incorporated in May, 1901.

The flames of the feud were further fanned by an incident in July 1901 when Melrose was accused of killing a dog belonging to one of Broome's family members.

The Melrose-Broome feud culminated in the famous 1903 gunfight, about which witnesses said Melrose intentionally ran into Broome with a wheelbarrow, causing a tirade of vulgarities from Broome. Melrose ignored Broome's epithets and silently walked down the street, with Broome at his heels.

When they reached the boundary of the Acton Hotel, Broome is said to have laid down his gun, taken off his coat, and called out Melrose to fight "fair and square." Melrose reportedly reacted by drawing his revolver and shooting the retreating Broome in the back of the scalp. As Broome fell to the ground, Melrose proceeded to beat him in the head with his revolver, and shot him three times in the torso. Broome died shortly thereafter from the injuries sustained in the fight.

At least that's one side of the story. Melrose told a different tale.

Melrose would claim that Broome intercepted him when he was taking his wheelbarrow home and cocked his shotgun while threatening to blow his head off.

After Broome laid down his shotgun, both men made a run for the gun, each grabbing an end of it, resulting in the accidental discharge of one barrel. Regaining possession of his gun, Broome attempted to shoot Melrose with the remaining barrel.

Melrose claimed he responded by first firing a warning shot into the ground. This having failed to stop Broome's assault, Melrose then took aim and shot Broome in the scalp, after which he removed the shotgun from Broome's possession and walked away claiming justifiable homicide.

Coroner's Jury

The headline in the Los Angeles Times of Jan. 22, 1903, screamed: "SHOT AND BEATEN AFTER HE DROPPED. Melrose-Broome Killing at Acton Cold-Blooded Murder, According to Coroner's Jury &mdsah; Bullet in Head and Three in the Body."

This was the initial conclusion of a coroner's jury that held court at the Acton Hotel the day after the gunfight, mostly based on eyewitness accounts of the incident.

The deck appeared to be stacked against Melrose. Most of Acton's citizens were in sympathy with the deceased Broome. Many had lived in fear of Melrose, calling him a dictator who had created terror in the town. The inquest had to be delayed a few hours in order to hunt out "jurors from their hiding places."

On autopsy, Broome was found to have bullet wounds in his abdomen, chest and upper left arm. There were no powder marks found on the body, supporting the assertion that Melrose fired his shots from a longer range and not during any grappling for Broome's shotgun.

After the gunfight, Melrose and his wife rode up to Lancaster where he turned himself in to Constable Oliver Mitchell claiming self-defense. He was brought back to Acton to face the coroner's jury, where his initial behavior was described as nonchalant and indifferent.

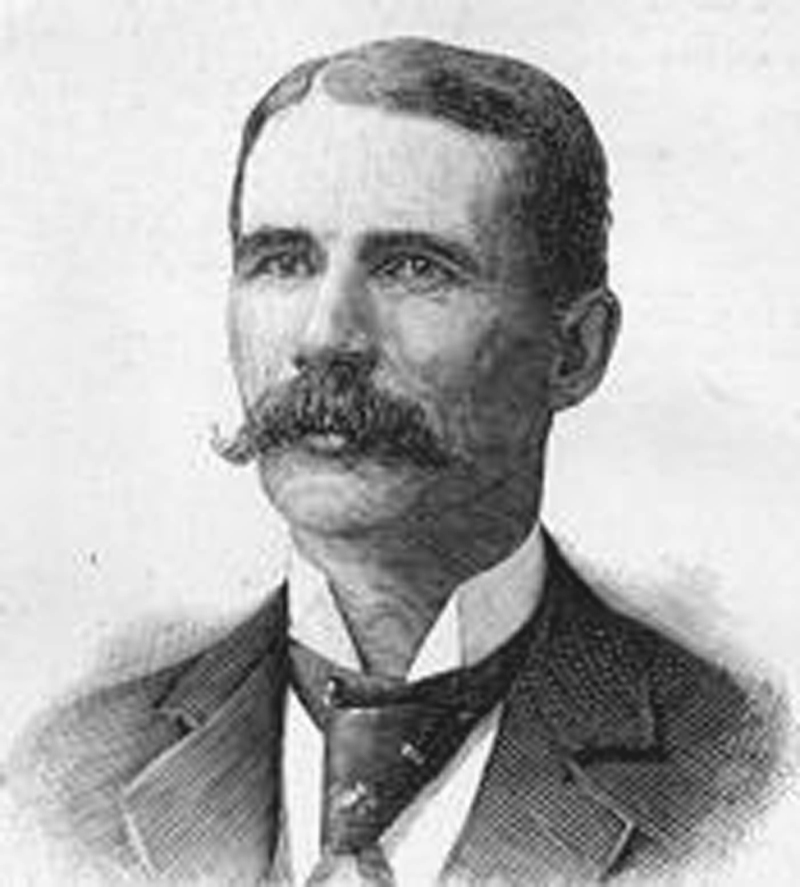

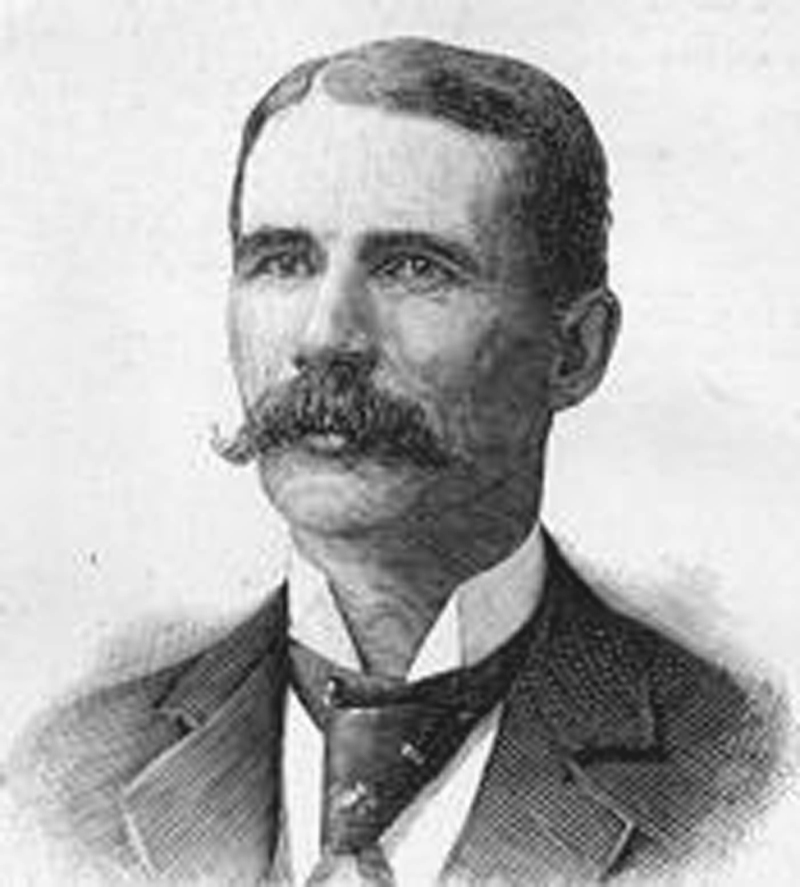

Norman M. "Rosy" Melrose glares at the Times camera while in jail.

|

Melrose was confident he would be acquitted. He stood stoically by and watched as the autopsy physician slashed open Broome's corpse to determine the path of the bullets that hit him.

Melrose's nerves of steel were reported to have melted, replaced by quivering when he was handcuffed and taken off to prison that evening after the inquest.

The newspaper reported, "In many respects Melrose is one of the most remarkable manslayers the county has ever seen, having besides education, wealth and many influential acquaintances, a most interesting personality. His wondrous eyes would mark him for notice in any crowd, and his strong, bronzed face and slender but sturdy form eloquently set off evidence of great nerve which is indefinable."

Melrose hired attorney Earl Rogers to defend him against the murder charges. On his first day in prison, he gave a "reception" for some 20 visitors, including four women. He was showered with fruit, flowers and other delicacies.

At that point, no charges had been filed, so he was allowed to stay separate from the other prisoners and bring in his own food from an outside restaurant. The L.A. Times opined, "To a man like Melrose it would be a little short of hell to be herded in with hobos."

A few days later, attorney Rogers and District Attorney Fredericks fought to outmaneuver each other in obtaining a favorable venue for the preliminary examination of Melrose. Rogers wanted it held at Lancaster, saying, "There is every reason why the examination should be held at Lancaster. The witnesses are all out there and that is where the shooting took place. It will save great expense to have it there."

But Fredericks arranged for the examination to be held at the court in Los Angeles, reasoning that it would save expenses as the attorneys were there, the exhibits were all there, and the defendant himself was there.

There was also a great deal of haggling over which justice would hear the case. The duty finally fell to Justice Austin of the Police Court.

Preliminary Hearing

The preliminary examination began Feb. 4, 1903. A large, standing-room-only crowd was said to have included many women and girls.

Two witnesses testified before the court that day. There was Charles Swanson, proprietor of the Acton Hotel and an eyewitness to the murder. Also testifying was August Schulte, an Acton bee raiser who witnessed the shooting and helped carry Broome into the hotel afterward. On the day of the gunfight, both men had been trying to scare up some pigeons from a nearby lot onto the roof of the hotel so Broome could shoot them with his shotgun.

They repeated the testimony that they had given before the coroner's jury in Acton, saying Melrose had shot Broome without a struggle for the shotgun. The newspaper reported that Rogers "spent most of the time trying to confuse the witnesses, but did not succeed very well."

The hearing continued the next day with more witnesses including Mrs. Selma Swanson, proprietress of the Acton Hotel, Mr. and Mrs. Ira L. Houser, Ernest Duehren (son of John F. Duehren, owner of the Acton Saloon and first resident of Acton), and Eugene F. Nichol. All told the same story of Melrose shooting an unarmed Broome. Of Melrose it was reported, "The unconcerned appearance of the defendant is one of the peculiarities of the case, which attracts everyone's attention."

The defense brought to the stand a local school teacher, Miss Minnie Elizabeth Boucher. She told of having sat next to Broome at the Burbank Theatre a few months prior to the shooting, and how Broome had talked of his troubles with Melrose, allegedly telling her, "I'll kill that man if I meet him."

Boucher said that on another occasion, she had been standing in the street in Acton talking to Mrs. Broome and Mrs. Melrose when Mr. Broome walked up, angrily holding a letter Melrose opened by mistake. He used violent language and again said, "I'll klll him, if I hang for it.”

Four others who followed Boucher in the witness box also related instances in which they'd met up with Broome and heard him threaten to kill Melrose.

After the defense rested, Justice Austin ordered that Melrose be held without bail for trial in the Superior Court.

Arraignment

Republican Congressman James McLachlan, a friend of Norman "Rosy" Melrose, represented Los Angeles County and neighboring counties in Congress from

1895-97 and 1901-11. California had just seven congressional seats until 1903, when it gained an eighth. McLachlan was usually elected by wide margins, although he lost to

a Populist Party farmer from Ventura in 1897 and to a Progressive Party member in 1911 who would go on to become governor, William Stephens.

|

Melrose was arraigned Feb. 12, 1903, for the killing of Broome. He reportedly looked deathly pale and haggard at the time.

In addition to Rogers and Luther Brown, Melrose hired a personal friend, the local Republican congressman, James McLachlan, to assist in the defense.

By March, Melrose had been set free on a $10,000 bond. The Los Angeles Express newspaper of March 18 reported that people who had testified against Melrose were fleeing Acton due to his high-handed actions. His lawyer branded the story "a tissue of falsehoods, absolutely without foundation in fact, and part of a conspiracy to create sentiment against his client in advance of the trial."

The defense planned to prove that the witnesses who had testified against Melrose falsified their stories out of hatred for the man. It also planned to prove the veracity of Melrose's assertion that the two men had been grappling for the shotgun.

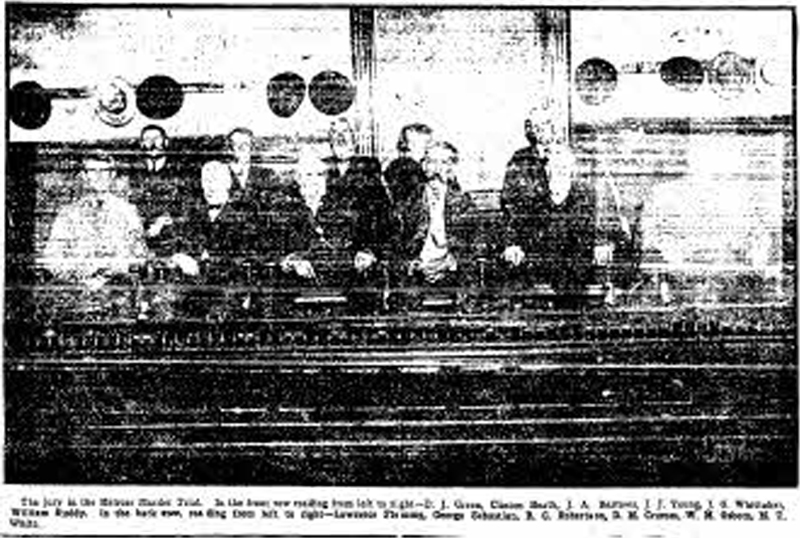

Jurors selected for the April 6 trial hailed from Long Beach, Downey, Pomona, Pasadena, South Pasadena, El Monte and Los Angeles.

First Trial

The Melrose murder trial began April 7, 1903, in the court of Judge Smith. The Los Angeles Times reported, "It seems as if the whole of Acton hated either one or the other of these two bitter enemies. About the whole population seems to be in Judge Smith's court. Those who do not effusively shake hands with Melrose, glare blackly at the back of his head as the tale unfolds."

The first witness for the prosecution was the Acton bee raiser from Germany, Mr. Schulte. He repeated his testimony from the preliminary examination.

The defense created a courtroom drama with one of the lawyers lying on the floor with a mock Melrose standing over him with a gun. They asked Schulte, "If those last shots were fired as you say, why were there no powder burns on Broome's body?" Shulte cheerfully replied, "I guess he use smokeless powder!"

The defense tried hard to make the witnesses look like liars. The Times reported, "It's no fun to be a witness at this trial." Private detectives had been hired by both sides to work up evidence against the other side.

The defense began presenting its case April 9. Attorney Rogers opened by claiming that the killing was an "outgrowth of an old feud between the Germans who settled Acton and the Americans who came in afterward. Broome and Melrose took it up bitterly." He claimed Melrose had been persecuted, the graves of his family at Acton desecrated, his trees cut down and his cattle poisoned.

Rogers said the feud came to a head when Melrose shot and killed a dog belonging to Broome, which had bit him. He aimed to prove that Broome was killed in a hand-to-hand scuffle while admitting that the last shot was fired as Broome was already falling. He characterized the last shot as Melrose "not being thoughtful."

Eugene Nichol, a German miner, was called to testify for the defense. He said Melrose had come to him after the killing and asked that he be a witness for the defense. However, he had not heard or seen Broome use his shotgun against Melrose. Alluding to the prosecution witnesses, Nichol said they "would not admit it if they had seen it."

The defense got Mrs. Swanson to admit she was unfriendly with Melrose as he apparently had caused her to lose a saloon license at the Acton Hotel.

Numerous other witnesses testified as to Broome's multiple threats to kill Melrose. The town schoolteacher, Miss Lillian B. Plato, testified that she had witnessed through a pair of field glasses that Broome was killed during a hand-to-hand struggle with Melrose and was not trying to run away.

The jury in the trial of Norman Melrose.

|

Melrose Takes the Stand

Testimony in the murder trial ended April 14. That day, Melrose himself took the stand. He was described as an excellent witness with an instinctive appreciation of dramatic effect.

Melrose and Broome had first met when Broome was a telegraph operator at Vincent. He told of the dog shooting incident and various instances when Broome, armed with a shotgun, attempted to kill him.

He told his version of the gunfight and the struggle for Broome's shotgun. He said: "As he turned he had the shotgun in his hand. I grabbed it by the muzzle with my left hand and it went off. Then I used my gun as fast as I could. At last it missed fire. Broome yelled, 'the damn ____ ____ has shot me, but I will get him yet.' Then I reached over and beat him over the head with my revolver with all my force. I did not hit him after he fell; I could not have, because my gun was jammed and would not shoot."

Asked by the prosecution how he was feeling at the time, Melrose replied, "I was feeling that self-preservation is the first law of nature."

Following the closing arguments, the jury went into deliberation. After 10 hours the jury reported that it was unable to agree. The judge ordered the jurors back to their room to try to reach a verdict. At the end of the evening, the vote stood at 7-8 for acquittal and 4-5 for conviction.

Sequestered for the night, the jurors went to bed saying it would be absolutely impossible for them to come to an agreement. It was a hung jury.

Second Trial

The prosecution decided to retry the case. By June, the town of Acton was split between friends of Broome who claimed that Melrose had "reduced the whole countryside about Acton to a frazzle of nervous terror," and friends of Melrose who claimed that "base emissaries of the Broome faction are abroad buying up testimony with whiskey."

Melrose's enemies accused him of parading around the terrified streets of Acton with a Winchester rifle and revolver. He was said to have an evil glimmer in his eye and to be drinking "gunpowder tea."

His supporters told tales of "detectives ... haunting the precincts of Acton seeking to lead innocent citizens to do no one seems to know just what, something that takes large and wicked quaffs of whiskey to do."

Some of the townspeople went before Judge Smith asking him to revoke Melrose's bail. He denied the request, to the outrage of the district attorney.

The second trial began July 7 with jury selection. Jurors came from Norwalk, Pomona, La Canada, Irwindale, South Pasadena, Compton, Azusa and Los Angeles. After 10 days of many of the same witnesses and much of the same testimony as the first trial, the jury deliberated and was able to reach a verdict, which they announced on July 17.

"People versus Norman Melrose. We, the jury in the above entitled action, find the defendant not guilty."

Upon hearing the verdict, Melrose kissed his tearful wife and shook hands with friends gathered around him. Judge Smith discharged him from custody, and Melrose and his wife walked over to the jury box.

The Los Angeles Times concluded, "Melrose and Mrs. Melrose where too much overjoyed to speak, and with the picture of the Acton killer and wife, shaking hands with the twelve men who held the life of Melrose in their hands for two weeks, the most famous murder trial in the history of the county came to an end yesterday evening at 6:35 o'clock."

Epilogue: What Ever Happened To Norman Melrose?

After publishing this article, we received the following message on June 20, 2013 from Steve Hoffman:

I came across Dr. Pollack's recent article on Norman M. Melrose while performing some genealogical research. Strangely, I'm related to Norman's wife, Florence (listed as Flossie in the article). In fact, Florence (who is my great-great-grandmother's step-sister) had written to my great-great-grandparents often, and even told my great-great-grandmother specifically that she was postmistress in Acton for years, just like it says in the article.

If I had any of Florence's correspondence (and the contents weren't too personal), I'd be happy to send you copies. Unfortunately, the only information I have comes from a paragraph in a very short family record (with no author listed) that I found, but here's the text from it as written:

Katie's other half-sister, Florence, also lived out in California. She was married to Norman Melrose in 1913. She used to write to Mary frequently. She had been post mistress in Acton, California for years. Her husband was a lawyer in Los Angeles. They had no children, but used to send toys and books to the McPhillips children when they were growing up. They were well to do and owned a gold mine in Washington. The last anyone ever heard from them was in October of 1913. She wrote a letter to Mary congratulating her on the birth of her daughter, Florence. She said not to expect mail for her for awhile, as they were leaving for the mine in Washington. That was the last anyone ever heard of either of them.

Corrections/Clarifications: Katie refers to Katherine McPhillips (nee Powers) of Chicago, and Mary refers to Mary Buckley (nee McPhillips) (Katie's daughter). Also, since Norman and Florence were listed as married in your article and also in the 1900 US Census, they were married long before 1913. The baby Florence Buckley was born Feb. 17, 1912 in Pine Co., Minn.

Needless to say, with that sort of mysterious "ending" to their story, I decided to look into it. Here's what I've learned:

Norman and Florence lived at 3418 1/2 South Hope St. in Los Angeles for several years. Norman died on Feb. 1, 1922 at Pacific Hospital in Los Angeles of peritonitis. He was buried on Feb. 4th at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, Cal. Florence died on July 23, 1929 at Kimball Sanitarium in La Crescenta of chronic myocarditis. She's buried next to Norman.

If you'd like a thorough history of the Melrose family, I came upon a great website maintained by Elizabeth Melrose that dates back to 1718. It also has a photo of both Norman and Florence on that front page, which were great finds for my own research:

[The Ward Melrose Family History]

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.