|

|

The Other Great Fire of 1906.

Blazes Erupt at Lang Hotel and Pico Oil Field; Develop Into Major Conflagration.

By Alan Pollack, M.D.

| Heritage Junction Dispatch, March-April 2015.

|

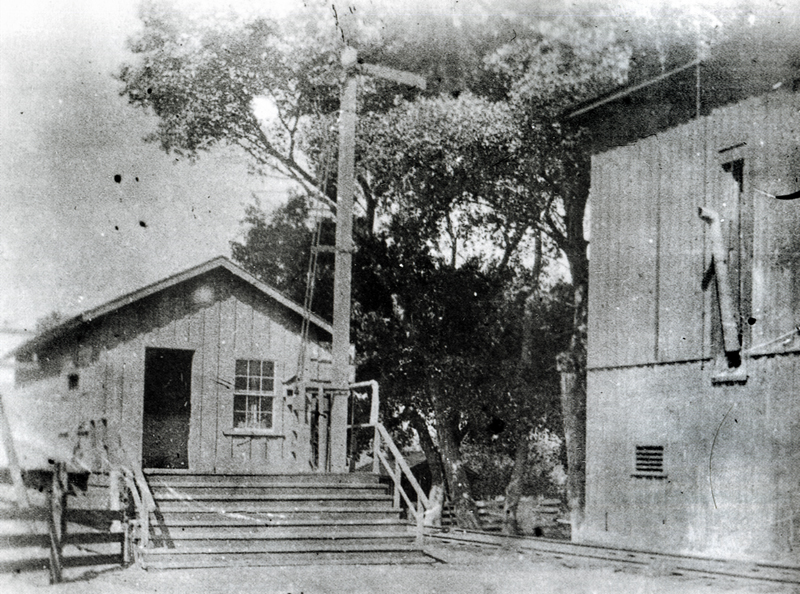

A mere six months after the greatest disaster in California history decimated San Francisco from earthquake and fire, a huge conflagration in the fall of 1906 almost dealt the same fate to the Santa Clarita Valley. It all started in the hotel at Lang Station in Soledad Canyon along the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Much like the fire that destroyed the elegant Southern Hotel in Newhall in 1888, it was believed to have been caused by a defective flue or spark from the chimney. Across the tracks from the hotel, a new train depot had recently been built. At 8 o'clock on the morning of Oct. 5, 1906, station agent Slayton noticed smoke curling up from the roof of the large frame hotel and sent out an alarm. Slayton stated: "Instantly the hotel became a roaring mass of flames." Sleeping in the hotel that morning was night operator McReynolds. Still in his white robe, he barely escaped with his life. According to the Los Angeles Times, "Other inmates were eating breakfast. The house seemed to explode with fire, so dry was the structure, and these people were forced to abandon it without saving any of its contents. C.H. Clayton of Los Angeles owned the hotel."

From Lang to Placerita Driven by a strong north wind, the flames from the hotel leaped over the tracks and quickly consumed the new train depot. After annihilating Lang Station, the flames spread along the tracks westward down Soledad Canyon. Three miles down the canyon, they reached the ranch of Deputy Constable Youngblood. The constable lost five buildings and an olive orchard. The fire advanced through Humphreys to the head of Soledad Canyon. It jumped across Whitney Canyon, destroying the houses and barn on the Nettleton & Kellner Ranch. As it proceeded into Placerita Canyon, the fire roared toward the Standard Oil Co.'s boiler house and pumping plant. Near the plant, residents of the canyon were eating lunch, including Dr. S.L. Wellington, who was visiting the canyon with his wife and granddaughter. "Our lives were spared by the narrow margin of five breathless minutes," Wellington said. "When I saw those flames tear through the twenty foot growth of underbrush like spray dashing high over rocks, and consume great oak trees like the flash of lightning reaching into the sky, fear came into my heart. Fear for the women and children who had been playing by the brook but a few moments before. "Most of the men who live in this canyon were away on business," he continued. "A man named Gibbs, A.M. Park and I, alone, had to drag the women to safety. It was terrible. ... We had no time to save anything. We were lucky to get out with the clothes on our backs. "We ran along the road until the fire raced ahead of us and blocked our way. We crawled through the underbrush and struggled up the hillside, only to be driven back to the bed of the stream, where we threw water upon our scorched faces and cupped it up in our hands to moisten our parched throats. I saw the hair of Mrs. Reynolds singed until I thought it would be burned entirely from her head. The clothes of the women smoked. Had a skirt caught the flame, I fear that nothing could have saved the threatened life." (Mrs. Reynolds was the wife of the superintendent of the Standard Oil plant.) Constable Ed Pardee saved the day when he rushed up the canyon road with horse and buggy to the fleeing residents. The women and children were packed into the buggy with Mrs. Reynolds taking the reins to drive them out of harm's way. The men were able to escape the canyon on foot. All of the buildings on the grounds of the Standard Oil pumping plant were destroyed except for the residence of Superintendent Clay Reynolds. The loss of the pumping plant cut off the water supply to the town of Newhall. From Placerita Canyon, the fire raced into Elsmere Canyon and then headed toward Newhall. The flames passed just southwest of the town and turned toward the Newhall Pass (then called the San Fernando Pass). There a stubborn group of firefighters, led by the superintendent of the Newhall Ranch, managed to save the homes of Duarte, E. Humas, C. Price, and K. Rivera. Pico Canyon Fire A second fire that day wreaked havoc in Pico Canyon. As told by eyewitness Ernie Moore, "The fire is supposed to have started from the gas in one of the wells. The place at once became a torch-light brigade as oil derrick after oil derrick leaped skyward in flame until twenty-four of them had been consumed. "The residences of Will Hitchcock and Will Biscailuz were licked up," he said, "along with a lot of employes' [cq] shacks, barns and outhouses. When the tank containing 60,000 barrels of oil tried to build a fiery ladder to Heaven, we all thought that our fight to save the Standard Oil Company buildings was hopeless. In fact for a while it looked as if we would mount that ladder along with everything else. "The heat was terrible, but we stuck it out and the flame, through God's will, stood straight. We saved the boiler house, the office building and the machine shop, and the residence of Superintendent Walton Young. ... Finally the fire flattened out and died a natural death in the hills about midnight, and we lay down in our clothes under the sky and slept until morning." In the mountains between Rice Canyon and Chatsworth in the San Fernando Valley were roaming 6,000 range cattle. Their lives were endangered as the flames leaped over the mountains between the two valleys. Cattle that had been evacuated from the burned district were taken over Beale's Cut down to the town of San Fernando. During the night, Martin Mahey and his wife rode up from Newhall into the dark canyons of the mountains to the south searching for their 150 head of cattle endangered by the flames. They found many of their cattle in clusters of two, threes and fours. The frightened animals were herded through smoke and falling cinders into the lowlands near Newhall. Section men and other gangs of the Southern Pacific Railroad were taken by special train into the fire district where, through their heroic efforts, several railroad bridges were saved between the San Fernando railroad tunnel and Lang Station. A section house at Lang Station managed to escape the flames. Here a crew of linemen worked to reestablish the telegraph connection at Lang. Late in the afternoon, Southern Pacific's Owl train crossed the Newhall Pass through a dense cloud of smoke and flames as it approached the San Fernando tunnel. The train entered the tunnel's mouth through "walls of red flame. The heat smote passengers, and the pungent fumes of deep-brown smoke filled their nostrils" (Los Angeles Times, Oct. 6, 1906). Into the San Fernando Valley Around 2 a.m. on Oct. 6, the fire was eating its way along the western slope of the Santa Susana Mountains toward Chatsworth. Two hundred fire fighters fought heroically through the night to try to bring the fire under control. The flames threatened the railroad station at the San Fernando Tunnel and the farms of the San Fernando Valley below it. The sky over the mountains was said to be reddened for miles. According to The Los Angeles Times, "Newhall was saved by 150 smoke-grimed, sweating men who fought with dampened sacks and back-fires after some of them had seen Lang go in ashes." Overall, 200 square miles of mountains were scorched on the first day of the fire. Heroes of the Disaster Newhall's Edward D. Kichline saved a sick woman and her babies who were camped in a canyon just north of the town. Kichline crawled on hands and knees 100 yards through burning brush to reach the woman, Mrs. Bicaluz [cq]. He found a small wagon and horse into which he threw the women and children and had them ride out of the area. Kichline continued on foot and found himself surrounded by flames. With his lungs filled with smoke and eyes blinded, he finally had to throw himself on the ground on his stomach with a wet gunny sack over his head. After the fire swept over him, he crawled on the ground through the flames for another 100 yards before he reached safety. Fred Dellarno raced the flames in Pico Canyon to save a group of horses. He did this while riding an old, blind horse that had trouble out-pacing the fire. Dellarno finally had to abandon the horse and run to a safe place. He returned later, expecting to find his dead horse, but instead he found the old animal grazing in a sheltered area which the fire had passed by. J.E. Over and George R. Harrison were among a group of five men trying to save lumber at Humphreys Station when they saw the flames heading toward Placerita Canyon, where some of their families were camping. The men abandoned the lumber and raced toward the canyon, arriving just in the nick of time to save the women. The lumber, unfortunately, about 6,000 feet of it, did not survive. Victor Over the Fire — Almost After three days of battling the flames in the San Fernando Mountains, fire fighters declared victory Oct. 7. The towns of Newhall, San Fernando and Chatsworth had been saved. Many ranchers were left homeless, and cattle and game had been burned to death. San Fernando was virtually depopulated of men who were dressed in their Sunday finest as they raced toward the mountains to save the town. Just when they thought everything was under control, the flames whipped up again in the mountains north of San Fernando. It took a hard day's work of 100 citizens of San Fernando to quash the resilient fires. It was finally over ... until the next time. Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.