|

|

|

St. Francis Dam Construction Records Missing

L.A. water officials weren't keen on preserving memories of thier biggest failure. By Peggy Kelly Originally published in Santa Paula Times | October 2, 2009 | |||

|

One wouldn't expect a general membership meeting of the LA as Subject Archives Forum[1] to involve passionate debate. Under the prestigious and umbrella of the well-heeled Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, members of the organization (known as LA as Subject) who hold documented history dear were in for a surprise when they learned in October 2008 that an important piece of the past was missing. According to the meeting minutes, "an invigorated debate" — one assumes that's gentle LA-as-Subject-speak for all hell breaking loose — over "proper archiving" took place. Specifically, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power purportedly destroyed many records, including information about the descendants of the St. Francis Dam disaster. "Related to LA as Subject, this reminded us how we need to be more forward with historic preservation of archival sources," the minutes state, a poke in the eye from the archive folks. "It was brought up that LAPL (Los Angeles Public Library) had, or still does have, a branch in DWP, and that we may want to inquire what type of collection they have." Loyola Marymount University hosted an October conference on "Water and Politics in Southern California," the probable target of the missing records referenced in the LA as Subject meeting notes, especially since a listed conference presenter was Dr. Paul Soifer, consulting historian for the DWP's Historical Records Program. Sofier's presentation was titled, "The Aqueduct, St. Francis, and Mulholland: The Records at DWP." Good luck, stalwart members of LA as Subject; the St. Francis, as in St. Francis Dam and Disaster, is no longer the stuff of detailed records kept by the DWP, and probably hasn't been for more than 80 years. For generations, the DWP and the city of Los Angeles have been trying to forget the whole St. Francis Dam thing. "In addition," per the LA as Subject meeting minutes, "the Berkeley Water Department has a very open relationship with the general public, something that should be modeled in Los Angeles." Ah, but then again, Berkeley didn't have the St. Francis Dam Disaster, a 12-billion gallon flow of water over more than 56 miles that started March 12, 1928, when the structure collapsed — or rather, exploded out from the walls of the usually serene San Francisquito Canyon.

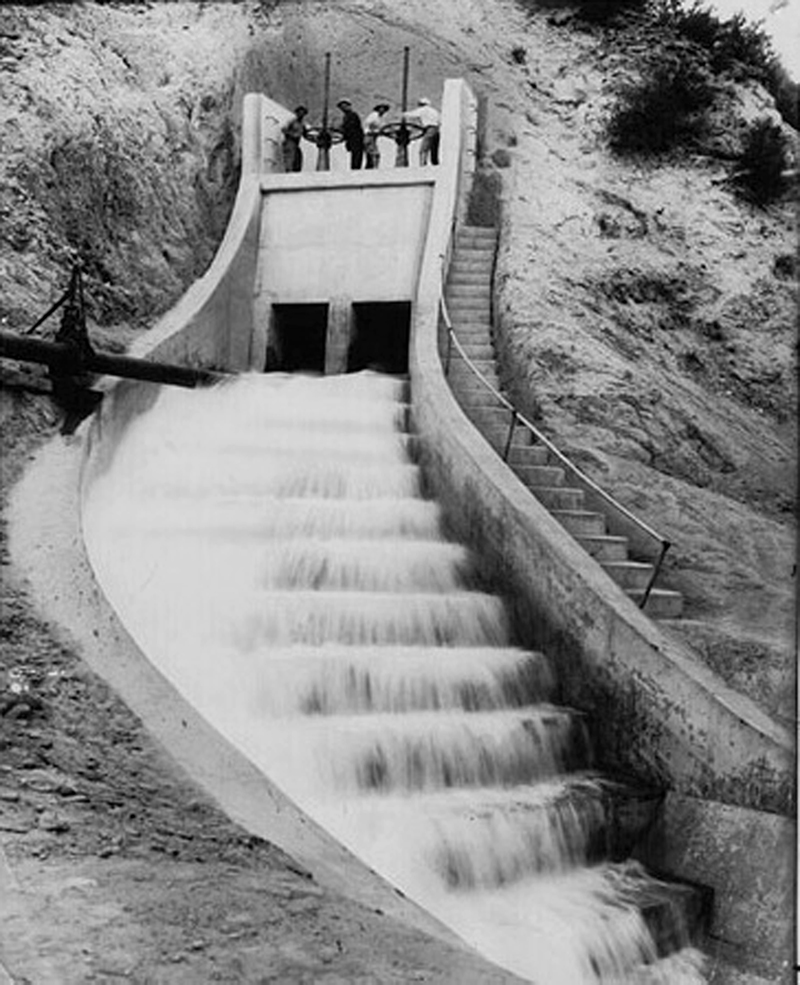

There's an extensive backstory to the St. Francis Dam, which was erected in record time to provide a year's worth of water storage to thirsty Los Angeles. A drought and then pesky attempts by Owens Valley farmers to disrupt the flow of water from the 1913 aqueduct created a municipal stampede to get the dam built. About a dozen years later, once the growers' lake had dried to the consistency of talcum powder, they attempted to blow up William Mulholland's stream of cool water that made possible the San Fernando Valley — a move that created that bit of panic. Construction of the St. Francis Dam started in March 1925, and a scant year later the Los Angeles Times, whose owners had greatly profited from the development made possible by the aqueduct, was touting the near completion of the dam and published the first photos of the structure. Already, the St. Francis Dam had an unholy connection to the month of March. In Ventura County, the Oxnard Daily Courier reported in July 1926: "The eighteen-month period required to complete the pour" — a timeframe earlier reported by The Times as a year, with a completion date of March 20, 1926 — "is considered by engineers to be something of a record in dam construction." Then it was time for the fill, and as the skies above the Golden State reversed the drought into record rain, the dam was declared in March 1928 to be up to its brim with 12-billion-plus gallons of water. The dam that had been built in what might be record time set another record of sorts when it blew out days later, a few minutes before midnight on March 12. Probably 1,000 people lost their lives, including half of the student body of Saugus Elementary School, who simply disappeared in the floodwaters. The flood widened and slowed in the Santa Clara River Valley, and the water absorbed more and more debris before finally spilling into the Pacific Ocean. The cost of the St. Francis Dam was $1.25 million, although no one could ever locate a real budget. It was 1,225 feet wide at its crest and 205 feet high — pushed up twice to store more water without any strengthening done to its toe. About 175,000 cubic yards of concrete were used to build the St. Francis, material that could have been the basis of a lawsuit centered on criminal negligence, according to a civil engineering professor who had it tested almost eight decades later. Thomas M. McMullen used the disaster as the cautionary tale and stark contrast-comparison for his master's thesis on the construction of Hoover Dam, but only after brief mentions of the doomed St. Francis started cropping up in his research. Next time: More from Thomas M. McMullen.

1. The LA as Subject Archives Forum is an association of archivists, artists, librarians, local leaders and researchers dedicated to improving the visibility, access, and preservation of archives and collections documenting the rich history of the Los Angeles region.

Peggy Kelly of Santa Paula is an award-winning freelance writer, humorist and sought-after Master of Ceremonies. In 2018 she became the owner of the Santa Paula Times newspaper. The working title of Peggy's forthcoming book is "Thornton's Wild Ride! The True, Untold and Unbelievable Story of the Hero of the St. Francis Dam Disaster." |

1) St. Francis Dam: Forgotten, With Purpose 2) Reopening the Books on the St. Francis Dam Disaster 3) St. Francis Dam Construction Records Missing 4) Dam Disaster Whitewash Preserves Mulholland Legend 5) Failing St. Francis: Water Pressure or Political Pressure? • Thornton Edwards, Hero of the St. Francis Dam Disaster

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.