|

|

William S. Hart Museum | Newhall, California

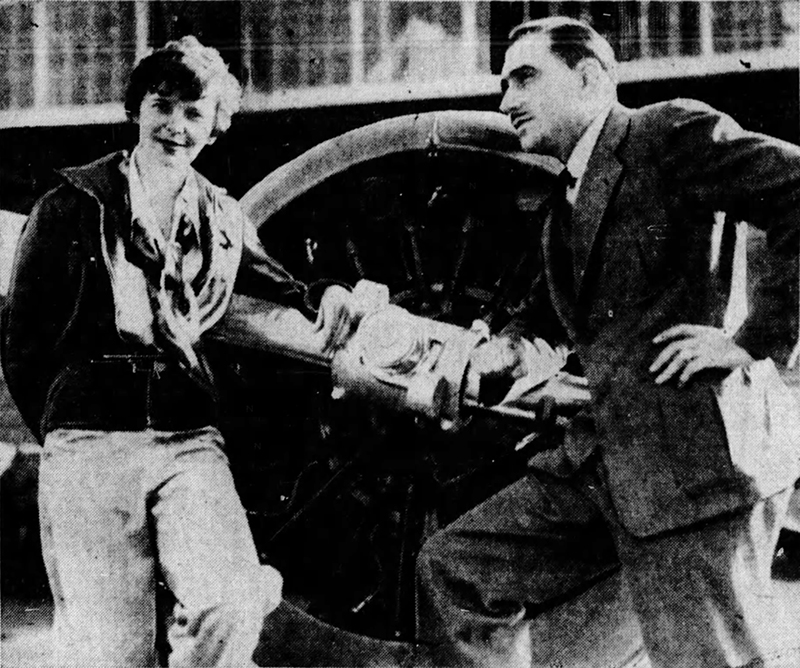

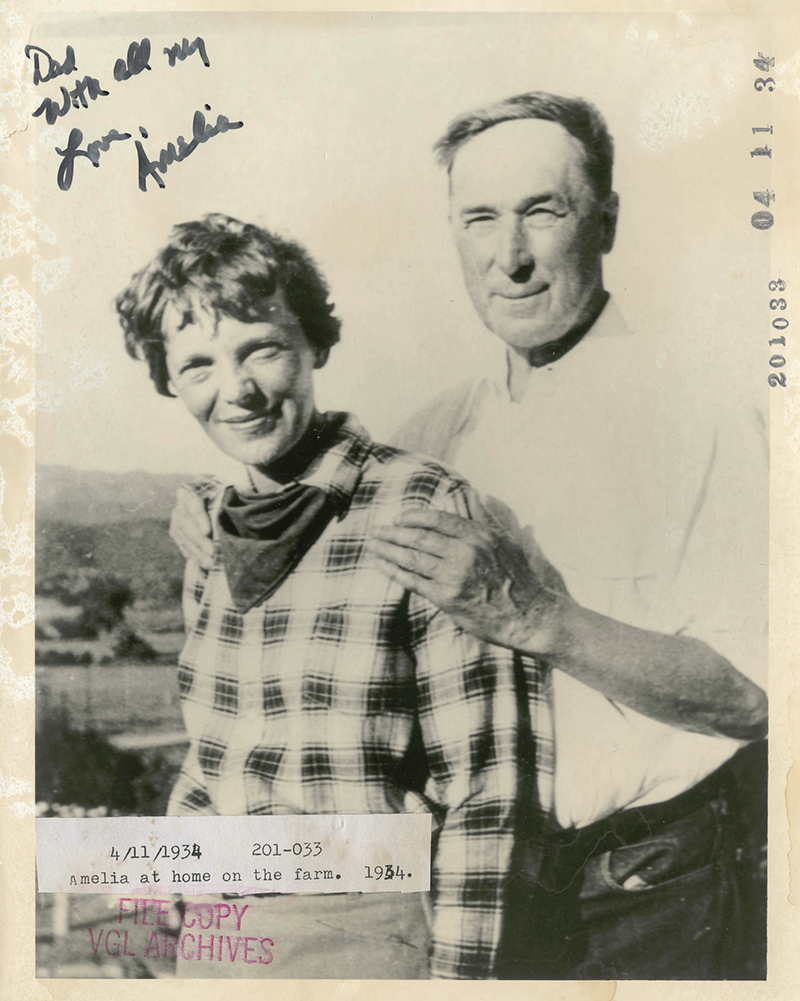

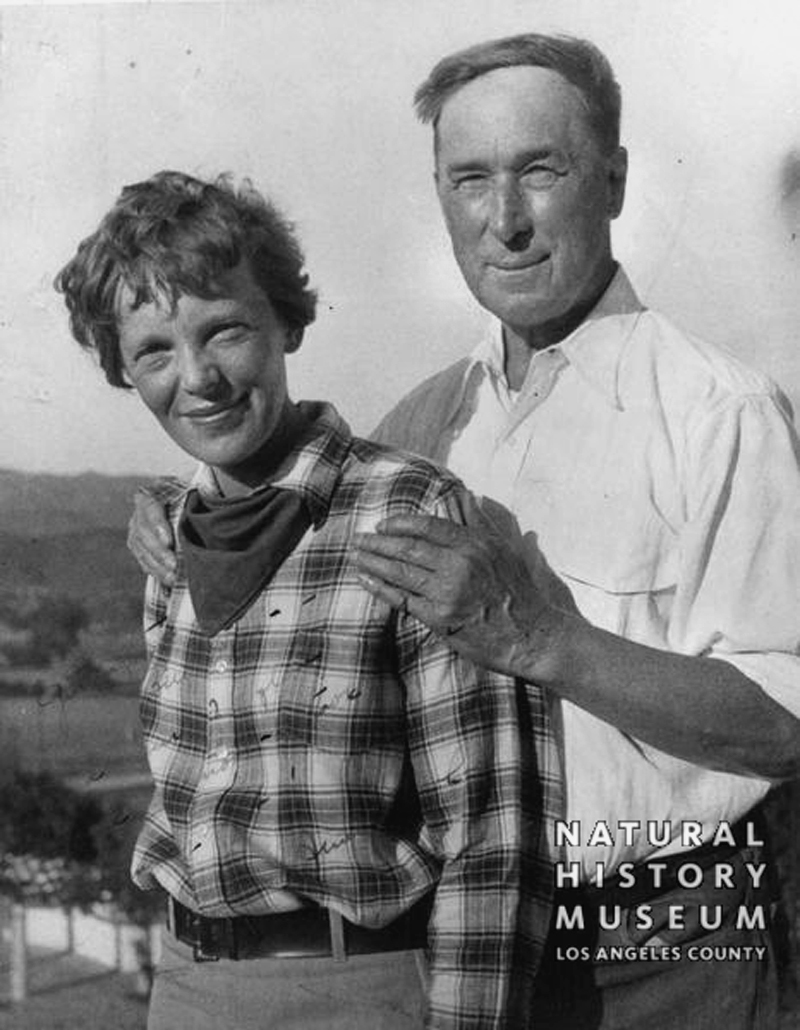

Actor William S. Hart (1864-1946) entertains aviatrix Amelia Earhart (1897 - disappeared 1937) at his Newhall estate. Original print on display at the William S. Hart Museum in Newhall. Four prints of this same photograph reside in the Purdue University Libraries archive, which houses the Amelia Earhart Papers. They were given to Purdue after Earhart's disappearance by her widower, George Palmer Putnam. One print (see below) is inscribed: "Dot / With all my Love, Amelia." The print is date-stamped 04-11-1934 and bears the typewritten notation, "4/11/1934 201-033 / Amelia at home on the farm. 1934." "Dot" would be Dot Leh, a friend of Earhart with whom she was in communication in early 1934.[1] We don't know if this photograph represents the first time Hart and Earhart met, although it is likely, based on a lack of any evidence that they knew each other previously, weighed against a modest wealth of evidence afterward. During the spring and summer of 1934, Earhart was trying out a new airplane engine, and she exchanged one Lockheed Vega for another.[2] Putnam, her husband and business manager, hired Paul Mantz to oversee the overhaul at Lockheed's Burbank plant. Putnam wrote in 1939: "Paul Mantz had borrowed AE's Lockheed Vega one day, and in the course of a landing and the Newhall field had flown lower than he should over Bill's home."[3] Annoyed, Hart tracked down the plane's owner from the tail number — and a friendship was born. Unfortunately, Putnam doesn't provide the date or even the year of the incident, and apparently the news of Earhart's visits to Hart's Newhall home did not make any newspaper. Putnam had met Mantz when the latter was working on the 1927 blockbuster film, "Wings." Putnam had sold the story to Jesse Lasky at Paramount. Precisely when Putnam introduced Earhart to him is unknown, although by 1934, when she was planning her flight from Honolulu to Oakland, Mantz "had long been AE's technical adviser."[4] Certainly she knoew him in 1932 when he gave flying lessons to Putnam's son from his previous marriage, David Binney Putnam.[5] Earhart and Mantz would eventually become business partners.

Years later, in March 1941, columnist Hedda Hopper visited Hart at his Newhall home and wrote: "The two things he prizes most are these: a photograph of himself taken with Amelia Earhart a week before she left on her tragic flight, and a tiny American Flag autographed by her, which she'd carried on every flight she'd taken. It was her good luck omen. He begged her to take it along, but she wanted him to have it."[6] The flag is a possibility. Putnam and Earhart were living in North Hollywood in 1937, and she was in the Los Angeles area. Earhart departed from Burbank May 21, 1937, destination Miami, for the first leg of her circumnavigational flight. But the best evidence, the date stamp on the print at Purdue, points to 1934 for the photograph.

1. Lovell, Mary S. "The Sound of Wings: The Life of Amelia Earhart." New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1989, pg. 204. It can't say "Dad;" he died in 1930. 2. Ibid. 3. Putnam, George Palmer. "Soaring Wings: A Biography of Amelia Earhart." New York: Harcourt Brace, 1939; Manor Books 1972 edition, pp. 234-236. 4. Ibid.: 255-256. 5. See Los Angeles Times, July 12, 1932. 6. As published in The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise, April 4, 1941.

Hart and Earhart. Legend has it that Amelia Earhart used to land at the Newhall Intermediate Field, aka Saugus Airport, in the 1930s. Everybody did; it was a popular landing strip for light aircraft in the 1930s and '40s. At least we know one of her planes landed there. It's how she ended up meeting William S. Hart. "Paul Mantz [Earhart's business partner and mechanic] had borrowed AE's Lockheed Vega one day," Earhart's widower wrote in 1939, "and in the course of a landing at the Newhall field had flown lower than he should over Bill's home." The writer, George Palmer Putnam, continues:

"Damn near shook the bricks out of the chimney," Bill sputtered later. He roared out of the house and got the number of the plane — NC965Y — which he promptly communicated to the sheriff. In due time the complaint caught up, via the local Department of Commerce inspectors, with the plane and pilot. "Before the trouble was straightened out," AE used to tell the story, "the plane's owner, being myself, went with the offending pilot to call on Bill. Paul to square himself, I because I wished to meet a man who liked to live on a hilltop and didn't want to be disturbed — both admirable ambitions."[1] Hart was "among [the] friends in California whom AE liked most," Putnam writes, and the sentiment was clearly mutual. Columinst Hedda Hopper wrote in 1941 that Hart counted a photograph of himself with Earhart, and a small American flag she gave him, as his most prized possessions.[2] "We'd sit on the porch while the evening shadows lengthened and little rabbits stole out of the brush romping noiselessly across the green lawn," Putnam writes. One of Hart's Great Danes "persisted in giving fruitless chase to the moon-struck bunnies." Describing Hart's Horseshoe Ranch as a "treasure-house of relics of its owner's bright yesterdays," Putnam remembers: "One of the last evenings AE and I spent there, Bill ran off for us a couple of his silent pictures — 'Tumbleweed' [sic] and one other. ... 'Amelia,' he said when the lights went up, 'I never made a bad picture.' She said she was sure of that."[3] In October 1936, Hart mailed Earhart a letter in which he said he was sending her a buffalo coat that had been used by the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars of the 1870s. She hadn't acknowledged the gift by February 1937 when Hart mailed her another letter, asking whether it fit. It's unlikely she ever acknowledged it. The following month, March 1937, she made her first aborted attempt at a circumnavigational flight of the globe; in June she took off for her second and last attempt.

We know she received the coat, because in early 1937 she gave it to a friend for safekeeping. At the time, Earhart and Putnam were staying on a friend's dude ranch in the foothills of Wyoming's Absaroka Mountains. The friend, Carl M. Dunrud (1891-1976), was building them a small log cabin near his Double Dee Ranch in Meeteetse. They had commissioned the cabin while vacationing with Dunrud in 1934.[4] In 1937, Earhart gave Dunrud a number of items she evidently intended to use later. Among them were the buffalo coat Bill Hart gave her and the leather jacket she wore on several of her historic flights. But there was no "later." When he got the news July 3, 1937, Dunrud stopped work on the cabin. Dial up the clock 30 years. One day, Dunrud walked into the Buffalo Bill Historical Center (now the Buffalo Bill Center of the West) in Cody, Wyoming, and handed over the items Earhart had given him to a close friend, Harold McCracken, the museum director. Among them were the flight jacket and the buffalo jacket from Bill Hart[5] — who, coincidentally, had been invited to the opening of the museum back in 1927. (Hart was in Montana at the time, but it's unknown, for now, if he got there.) More years passed, and somehow or another, the buffalo jacket was misidentified as having belonged to Buffalo Bill. John Rumm, the museum's curator from about 2008-2015, previously with the Smithsonian Institution, corrected the error.[6] There is at least one other item Bill Hart gave to the famous aviatrix. It is a copy of his 1929 autobiography, "My Life East and West," which he inscribed to "a great American, Miss Amelia Erhart," her surname misspelled. The inscription is dated 1936. We don't know, but it's possible he sent it with the coat. We do know she received it, because it's got her bookplate in it: "From the Library of Amelia Earhart." At some point fairly early after her disappearance, it ended up in the library of Miles Standish Slocum, a prominent Pasadena book collector who focused on the literature and history of the American West. After Slocum's death in 1956, it passed down eventually to his granddaughter.[7] In August 2018, by way of the granddaughter's nephew, Bryan Woodhall of Custer, South Dakota, the book came home to Newhall where it started.

1. Putnam, George Palmer. "Soaring Wings: A Biography of Amelia Earhart." New York: Harcourt Brace, 1939; Manor Books 1972 edition, pp. 234-236. 2. As published in The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise, April 4, 1941. 3. Putnam, ibid. 4. Lovell, Mary S. "The Sound of Wings: The Life of Amelia Earhart." New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1989, pp. 204-205. 5. Rumm, John. "Her Plane Vanished. Her Flight Jacket Didn't." Blog post, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, March 17, 2014. 6. Baskas, Harriet. "The Surprising Home of Amelia Earhart's Flight Jacket." Blog post, Stuck at the Airport, September 30, 2013. 7. Bryan Woodhall, personal communication, August 2018.

MU8491: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's Seaver Center for Western History Research, Catalog No. GPF-8491. |

Discovery Guide & Map 2017

Last Will & Testament of William S. Hart 1944 Real Estate Acquisitions 1921-Date

Timeline: Operational Management of Museum, 1958/1988

Master Inventory 1971

Inventory: Missing Items 1963/1971

Charles M. Russell Portrait 1908

10 Millionth 'T' 1924

Hart at Ranch ~1920s

Const. 1926-27 x5

Construction 1927

Construction 1927

Flagg Presents Portrait

1930 x2

RPPC ~1930s

Amelia Earhart

Robert Taylor Photo Shoot 1941: BTK Gun, Fritz's Grave (Mult.)

Fire Threatens 1942

With Dan White ~1945

Letter from Hart to Flagg 1945

RPPC ~1950s

Frew Addition 1958

Park Dedication 1958

Dedication 1958

Entrance ~1958

Photo Gallery 1958/61

1959 x3

Bubnash Family Picnic 1959

Brochure 1960s

Visitor at Turret ~1960s

RPPC ~1960s

Times Story 1962

Aerials 1963

Brownie Playday Patch 1967

Dogs' Graveyard, Turret, Fritz's Grave 1967

Interiors 1968 x5

Exteriors, Barnyard 1968 x5

Picnic Grounds Cleanup 1973 (Mult.)

Friends of Hart Park: Initial Bylaws 1981

Donor List: Friends of Hart Park & Museum

Hart's Walk of Stars Plaques

Resolution 1986:

FOHP Founders

Pole Barn ~1998

Let's Go L.A. Video 2013

In Memoriam: Norman the Steer 2005-2017

Reckless Driving Bench 2017

NHMLA Volunteer Honors 2018

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.