|

|

Monogram Rough Riders

Click image to enlarge

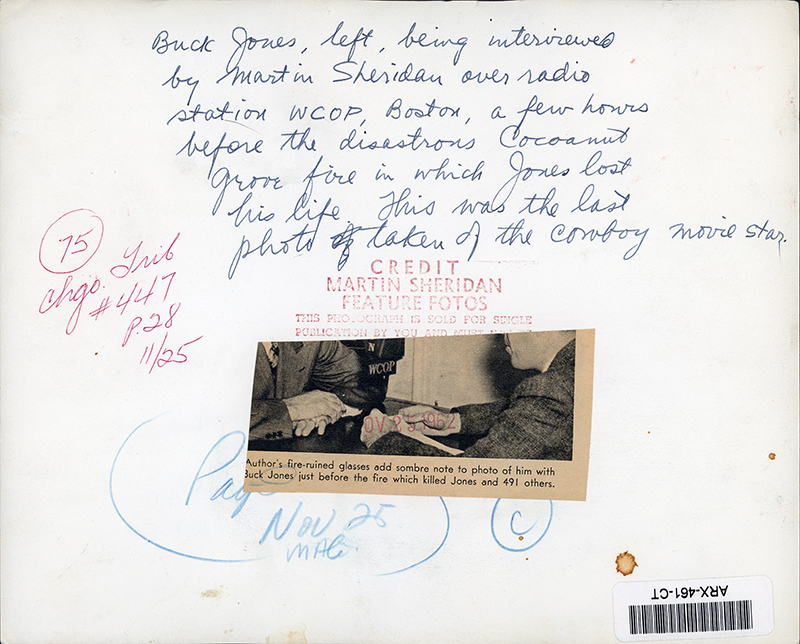

November 28, 1942 — Buck Jones, left, star of the Monogram Rough Riders buddy pictures shot at Monogram (later Melody) Ranch in Placerita Canyon, with radio host and promoter Martin Sheridan at the WCOP studio in Boston. Photo from the archive of the Chicago Tribune. According to the Chicago Tribune, this is the last photo ever shot of Jones, just hours before he was mortally wounded in the Cocoanut Grove fire. Traditionally, what's considered the last photo of Jones shows him visiting a children's hospital in Boston. However, the hospital visit occurred earlier in the day. There is some conjecture that a photograph of Jones and Sheridan may have been shot in Sheridan's hotel room after the radio interview, but as stated, that's conjecture. This is, at least, the last known photo showing Buck Jones alive. This 8x10 glossy print accompanies the story by Martin Sheridan which appears below. From Martin Sheridan Feature Photos, this exact print was published in the Tribune (see below) on Nov. 25, 1962 — roughly coinciding with the 20th anniversary of the catastrophic fire. As indicated, Sheridan was one of 25 people in Scott Dunlap's party at the nightclub, of whom only seven survived — including Sheridan and Dunlap. My 30 Seconds in Hell Sheer panic struck the crowd trapped in the blazing Cocoanut Grove night club. The memory of it still haunts the few who lived thru it. Here's one survivor's story. By Martin Sheridan. The Chicago Tribune | November 25, 1962.

I celebrate Thanksgiving twice each year. Once for the traditional feast, again on the 28th for just being alive. Wednesday will be the 20th anniversary of the Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston and — tho most Americans have forgotten the details of that sudden holocaust — the facts and the scars will always remain with those of us who survived. The fire started in a basement cocktail lounge when a busboy held up a match so he could see to replace a light bulb. The decorations caught fire and flames spread rapidly to the main dining room where plastic chair coverings ignited and filled the club with carbon monoxide. The more I think of it, the more I am convinced of the powerful role played by fate in all our lives. For example, if Buck Jones, the western motion picture star, had kept to my original schedule, at the time of the fire we would have been visiting the Buddies' club on Boston Common, where I had arranged for him to entertain servicemen from 9:30 p.m. on. Instead, because of a bad cold, he asked me to cancel his final stop on a hectic day-long schedule. But let's turn back 20 years... Fate Assembled the Victims I had been asked to arrange a Boston agenda for Buck, who had come out of retirement to help sell war bonds and to make a few quickie western action films during the absence of younger stars (such as Gene Autry) who were serving in the armed forces. Buck and his producer, Scotty Dunlap, arrived in Boston on the last stop of a nationwide tour. The next morning — the fateful Saturday — a police escort sped our group to Boston's Children's hospital where Buck visited several wards to entertain bedridden youngsters. Next stop was Boston Garden, where he spoke to a captivated audience of 10,000 boys and girls gathered for a rally sponsored by a newspaper. Then there was a small luncheon with leading Boston motion picture exhibitors and the press. Buck, who had arrived with a cold, sat thru three frigid quarters of the memorable Boston college-Holy Cross football game in the late Mayor Tobin's box at Fenway park that Saturday afternoon. He met me at radio station WCOP where I interviewed him on the air at 4:30 p.m. The big news in the newspaper offices that day — at least until 10:20 p.m. — was the tremendous upset scored by Holy Cross over a highly favored Boston college football team that led the nation both in offensive and defensive play. The final score was 55 to 12, and by early evening downtown Boston was teeming with Holy Cross alumni and fans celebrating the victory. At 7 o'clock, Buck and I were attending a cocktail party in his honor in Newton, a suburb of Boston. His cold had worsened and he asked me to cancel his date at the Buddies' club. I did; then 25 of us were invited by our host to have dinner at the Cocoanut Grove. The night was bitter cold and the streets icy. On the way downtown I stopped at my apartment to drop off a camera case with the films of Buck I had taken during the day. We entered the night club at 9:30 and were led thru a crowd waiting for tables to our reserved section on the terrace opposite the bandstand. The Grove was a popular club which offered the usual food, drinks, crowded postage stamp dance floor and boring floor show presented amid palm decorations supposed to resemble a tropical setting. I had never been in the place before. My seat was next to the back wall, about as far from an exit as one could be. The wall felt warm when I touched it. Tables were set so close together that backs of chairs rubbed against each other and waiters were hard-pressed to serve us. We never got beyond the first course and only seven of our group lived to eat another meal. I had barely finished an oyster cocktail when a buzz of voices crescendoed in a corner. At first I thought they were saying, "Fight." Thinking it was a contest between overexuberant football fans, I paid no attention. Suddenly a cloud of black smoke poured into the jammed room and I realized those voices were crying, "Fire! Fire!" Then came the loud crackling of flames sweeping thru the pseudo-tropical decorations. Nothing to get excited about, I decided. Just keep calm and walk to an exit. But where were the exits? I arose with the others in our party and took only one step when the lights went out — literally and figuratively. The blackout undoubtedly was one of the contributing factors to the large loss of life. It fanned the crowd into total panic. I shall never forget the screams and cries of the trapped, the crash and clatter of overturning tables and chairs, the smashing of dishes and glasses. I began to choke from the mysterious fumes that swept the Grove and then the world caved in on me. All of this happened within 30 seconds. When I came to I was barely able to gasp in the terrific heat and thick smoke. I could hear weak moans about me, the blows of the firemen's axes and the splashing of water. Even if I had known where the exits were — and several were blocked illegally by false walls — I couldn’t have helped myself or anyone else. I was in shock, shaking violently and unable to move or raise my voice for help. After what seemed and eternity I heard footsteps. I moaned as loud as I could. The steps came closer, then someone pulled me to my feet, walked me over debris and soft bodies to an exit. I was propped in a chair outside in the below-freezing temperature. It was quite a battle to keep from falling off the chair. My clothes were soaked from the fire hoses. I sat there shaking, fighting to remain upright, unable to see because both eyes had puffed shut from burns. My seared hands felt like the flesh was hanging from them. Finally, someone helped me into a taxicab. I remember asking the driver where we were going. He said, "Massachusetts General hospital." Someone in emergency asked if I knew my blood type. Having given a pint of blood to the Red Cross a few weeks earlier I directed the aid to the card bearing the Type A information in my billfold. This saved about 30 minutes in starting my treatment. They began to remove my wet clothing, then gave me a hypodermic to ease the intense pain. That was the last I remembered for three days. Meanwhile, back in the newspaper and press association offices the seriousness of the holocaust rapidly became apparent. By 11 p.m., 40 minutes after the first alarm had been sounded, the death toll was 200. By 3:30 a.m., police had reported 386 fatalities. The casualty figures continued to climb during the next 72 hours to more than 480. Buck Jones died from a combination of burns, carbon monoxide poisoning, and pneumonia. It was fortunate, indeed, that I was taken to the Massachusetts General hospital. In addition to being one of the top 10 hospitals in the country, it was not as crowded after the fire as other Boston hospitals and the injured were given emergency treatment more rapidly than elsewhere. Equally important was the fact that it was one of six hospitals in the United States ready with a complete wartime disaster plan and a supply of the then-new miracle drug — penicillin. Furthermore, the hospital had just completed two research projects on burns for the government's office of scientific research. Physicians and nurses worked around the clock to make us comfortable. The medical profession can be proud of the way its members tackled the disaster, many performing tedious operations and skin grafts without charge. For Those Who Lived ... A Lasting Fear On the morning of Jan. 25, 1943 — 60 days, seven blood transfusions, and two skin grafts after the fire — my hands and face were nearly healed and I was ready for discharge, subject to additional skin grafting on my hands. My return to normal activities was slow, but in May 1943, I joined the staff of the Boston Globe and became a war correspondent. Sometimes I marvel at my own recovery when I think of the plight of many survivors for whom those few seconds of sheer panic meant scars far worse than those left by their burns. Soon after the disaster, psychiatrists visited all the patients. One reacted to the news of the death of a relative by an extreme state of excitement and paranoid suspicions of the hospital workers. While most of the injured were cooperative, a few resented the efforts of the mental health specialists to help them. Some victims found that after leaving the hospital their difficulties became more pronounced. One girl's nervous tendency developed into a full-blown claustrophobia. Another could not visit a restaurant without imagining that a fire was breaking out and tables were overturning. A theater owner in our party who escaped with only slight burns found himself unable to sit in his own theaters. Most of the victims attempted to avoid crowded places and became extremely conscious of fire prevention equipment and exit signs. Today, I am still highly observant of exits in public places I visit. Despite changes in building codes throughout the United States and in many countries thruout the world, I continue to find serious violations of the law such as doors in public places opening INWARD instead of outward, and even locked emergency exits. I steer clear of places with revolving doors minus conventional doors adjoining them. While living at the now razed Hollywood hotel in the film capital 15 years ago, I became suspicious of the water-holding ability of the dirty, dust-covered fire hose outside my room and opened the water valve for a moment. The water never did reach the nozzle because it leaked out thru the rotten hose onto the floor and thru the ceiling below. I moved the next day. Several years ago, a falling icicle knocked out a power transformer and with it every light in an Evanston hotel where my family and I were spending a few days. Despite the fact that hotels, restaurants, manufacturing plants, and other public gathering places are required to maintain an inexpensive emergency lighting system, not an exist was lighted in the building. I know because I stumbled down six unlighted flights of stairs to the lobby with a daughter in my arms. Another time we were in a Loop theater awaiting curtain time when I smelled smoke. Firemen quickly extinguished a small fire in a storeroom. Out of curiosity I check the emergency exits in the theater and found some of them locked. The Cocoanut Grove holocaust and the Our Lady of Angels school fire would never have resulted in such tremendous and needless loss of lives if the buildings had been protected by automatic fire sprinklers. It takes disasters such as these to remedy weaknesses in building codes and inspection regulations. Unfortunately, laws are only as effective as the men who are supposed to enforce them. In the Cocoanut Grove case there were scores of local and federal laws being violated by the management, undoubtedly with the connivance of officials. There were indictments, trials, suspensions, and inquests for months after the fire. Only one person, Barnett Welansky, the Grove owner, was convicted and sentenced. He served nearly four years of a 12 to 16-year terms and was released to die at home of cancer. Today, the old Cocoanut Grove site in Boston is occupied by a motion picture film delivery service. The event of 20 years ago is nearly forgotten except by those of us who survived the fire and by those who lost loved ones in it. About Buck Jones.

The Life and Untimely Death of Buck Jones. Buck Jones was an A-lister among the "B" Western actors of the 1920s-30s-40s. A popular hero of dime novels and comic books, promoter of Grape-Nuts cereal and Daisy air rifles, Jones frequently starred in films shot at Placerita Canyon and Vasquez Rocks, and he came out of retirement during the war, when younger stars were off serving, to co-star in eight "Rough Riders" buddy pictures for Scott R. Dunlap at Monogram (after Dunlap had made a mid-career move in the 1930s to serve as Jones' business manager). The end of Jones' career didn't come by choice. He died as a result of traumatic burn injuries sustained in the famous Cocoanut Grove fire of Nov. 28, 1942, the deadliest nightclub fire in U.S. history. Flames started downstairs and quickly spread through the Boston nightclub; a single revolving door was the only way out. Jones was counted among the 492 casualties when he died at a hospital two days later. Jones was at the Grove because Dunlap was throwing a party in his honor. Dunlap was seriously injured but survived. Monogram exec Trem Carr was credited (or blamed) for spreading the rumor that Jones sustained his fatal injuries when he rushed back into the burning building to rescue victims, but in fact Jones was trapped behind a wrought-iron railing that incapacitated him in his seat directly across from the bandstand. Born Charles Frederick Gebhart on Dec. 12, 1891, in Vincennes, Ind. — some sources erroneously say Dec. 4, 1889 — he joined the U.S. Army in 1907 at age 16 and earned the Purple Heart during a rebellion in the Philippines. Discharged in 1909, he pursued and interest in auto racing and went to work for Marmon Motor Car Co. He reenlisted in the Army in 1910 and served until 1913, after which he busted broncs on the Miller Bros. 101 Ranch in Oklahoma where he met his bride, Odille "Dell" Osborne. The outbreak of World War I saw him training horses for the allies. Later, a Wild West Show took him to Los Angeles where he got work at Universal as a $5-a-day stuntman and actor. He went to Canyon Pictures and then to Fox Film Corp., earning $40 a week for stunt work. Fox eventually used him as a backup to Tom Mix, raised his salary to $150 a week, and gave him his first starring role in 1920's "The Last Straw." By the mid-1920s he was at least as big a star as Mix, Hoot Gibson or Ken Maynard. In 1928 he formed his own production company, but it was ill-timed. The silent period was closing and Westerns fell into a brief decline; and when the stock market crashed the following year he lost his shirt. He then tried to form his own Wild West show but it, too, failed, and after a year away from the screen, Jones landed at the Poverty Row studio Columbia Pictures at $300 a week, a fraction of his top silent-era salary. (Columbia hadn't yet broken out with 1934's "It Happened One Night.") Westerns roared back in the 1930s and Jones did, too. His masculine voice caught on with audiences as he starred in pictures for Columbia and Universal which were often shot in the Santa Clarita Valley. At one point he received more fan mail than any other actor. The early 1940s saw him co-produce a string of movies with his friend Dunlap, who teamed him up with Tim McCoy and Raymond Hatton to form the Rough Riders. Further reading: Buck Jones, Bona Fide Hero by Joseph G. Rosa, 1966.

LW2819b: 9600 dpi jpeg from original 8x10 glossy photograph purchased 2015 by Leon Worden. |

Bio/Story 1966

Tobacco Card 1920s

Tobacco Card, Portugese Colonies, 1928

The Avenger 1931

One Man Law 1932

FULL MOVIE

Outlawed Guns 1935

FULL MOVIE+

Stone of Silver Creek 1935 (Mult.)

"Black Aces" 1937

Walker Cabin

Boss of Lonely Valley 1937

Buck Jones Club Badge 1937

Forbidden Trail 1941

FULL MOVIE

Rough Riders 1942

Rough Riders 1942

Down Texas Way 1942

Ghost Town Law 1942 (mult.)

West of the Law 1942

Last Photo 11/28/1942

Dies in Cocoanut Grove Fire

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.