|

|

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Click image to enlarge

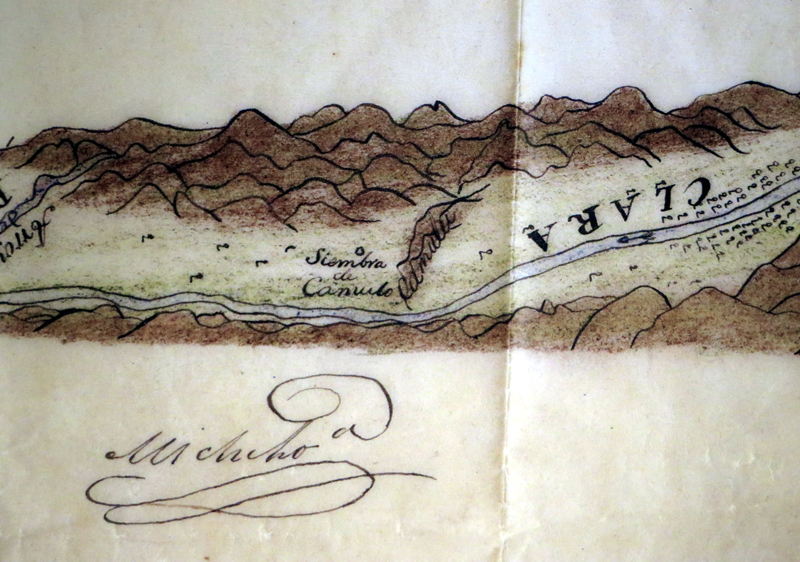

Diseño of Rancho San Francisco. Reproduction. At the time this map was drawn, it included most of the Santa Clarita Valley. On display in the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's permanent "Becoming Los Angeles" exhibit, which opened July 14, 2013. SCV Connection: This is a map of the Santa Clarita Valley as it was known in the early 1840s when it was owned by the heirs of Antonio del Valle. We don't know exactly when or why this map was drawn; according to the Natural History Museum signage it dates to 1854, but that is not possible because it is signed by Manuel Micheltorena, who was governor from 1842 to 1845. California became a U.S. state in 1850; Micheltorena, who didn't hold office under American rule, died in 1853. Landowners were required to file diseños (plan maps) during Spanish and (especially) Mexican period; most ex-mission lands were granted to private owners under Mexico's Secularization Act of 1833. This diseño differs markedly from another map of the rancho, believed to date to 1843. We hate to speculate, but after the original owner, Antonio del Valle, died in 1841, his son Ygnacio had a devil of a time fighting off competing claimants. Perhaps a re-mapping was needed for a legal proceeding. That's likely, inasmuch as Perkins says this, citing Bancroft: "In 1843, the title of Camulos was momentarily clouded by a grant to Pedro Carrillo, but examination showing the overlap on the Rancho San Francisco Grant, the Carrillo grant was nullified." Rolle (1991:66) and others note that during the Mexican period, the holdings of Antonio del Valle, who had been administrator of the Mission San Fernando, were presumed to include all 102,000 acres (see Perkins) of the ex-mission's lands: "After Ygnacio del Valle succeeded his father, Antonio, as owner of Rancho San Francisco," Rolle writes, "he confronted a host of seemingly insuperable problems. He had to raise money to purchase his sister Magdelena's share of the ranch and to 'prove up' his title to it under American law. Not until 1855 were squatter and other competing claims to Rancho San Francisco dismissed. Only in 1858 did Americans make the first patent survey of the rancho. Though quite rough, it described an area of some one hundred thousand acres. But del Valle, like other Latino land owners, was hard pressed to pay attorney fees and survey costs." Nor could he afford to prove it up (make improvements). The 1858 survey would have resulted from the (American) Land Claims Act of March 3, 1851, which required all persons who owned land under Mexican rule to file a claim, within two years, with the three-member Board of Land Commissioners. The prior government had accepted boundary definitions that were little more than "this rock over here to this tree over here to that river," but the U.S. government had a stricter sense of metes and bounds. The commission judged the claims, granted patents for those it upheld (with better-defined boundaries), and rendered the rest to the federal government, which granted them to homesteaders in 160-acre parcels. The 1858 survey fixed the rancho's boundaries at 48,612 acres. Not until 1875, long after the Del Valles had been forced to sell most of the ranch to pay creditors, did the U.S. government finally issue the patent. Museum signage reads: Diseño of Rancho San Francisco, 1854. Not to scale. Original size: 28x17 in. Editor's note: It's not 1854. The display, a reproduction, is probably to scale of the original, but the original is not to the scale of the valley's actual features. Considering the distance of Piru to Camulos at left, Soledad Canyon — between the "o" of Rio and the "d" of De — should be much farther to the right.

About NHMLA's "Becoming Los Angeles" Exhibit: The 14,000-square-foot permanent exhibition is the largest in the Museum. It tells stories in six major sections: Los Angeles and the region at the time of Spanish contact; the Spanish Mission Era; the Mexican Rancho Era; the early American Period; the emergence of a new American city in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; the Great Depression and World War II, to the present. Some of the stories are well known, such as how the acquisition of water through the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913 allowed Los Angeles to grow. But there are other natural and human influences might surprise you: how cattle, the Gold Rush, floods, a plague of grasshoppers, railroads, and outlandish booster campaigns all played a part in transforming the region into an agricultural and industrial empire; the pivotal role Los Angeles played in World War II; and the dynamic diversity of the earliest settlers. Come meet L.A.'s Native Americans, colonists and settlers; rancheros, citrus growers and oil barons; captains of industry, boosters and radicals; filmmakers, innovators and more.

LW2570b: 19200 dpi jpeg from digital image 11/23/2013 by Leon Worden. |

La Puerta: Gateway to Santa Clarita Valley

~1843

Early-mid 1840s

1/3/1870

June 1874

Index

Actinolite Canoe by Ted Garcia 2012 x4

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.