|

|

Cañon del Buque.

Origin of the Name, Martin Ruiz Adobe, Suraco Family, Tiburcio Vasquez.

Historical Society of Southern California Annual | Vol. 14 No 2, 1929.

|

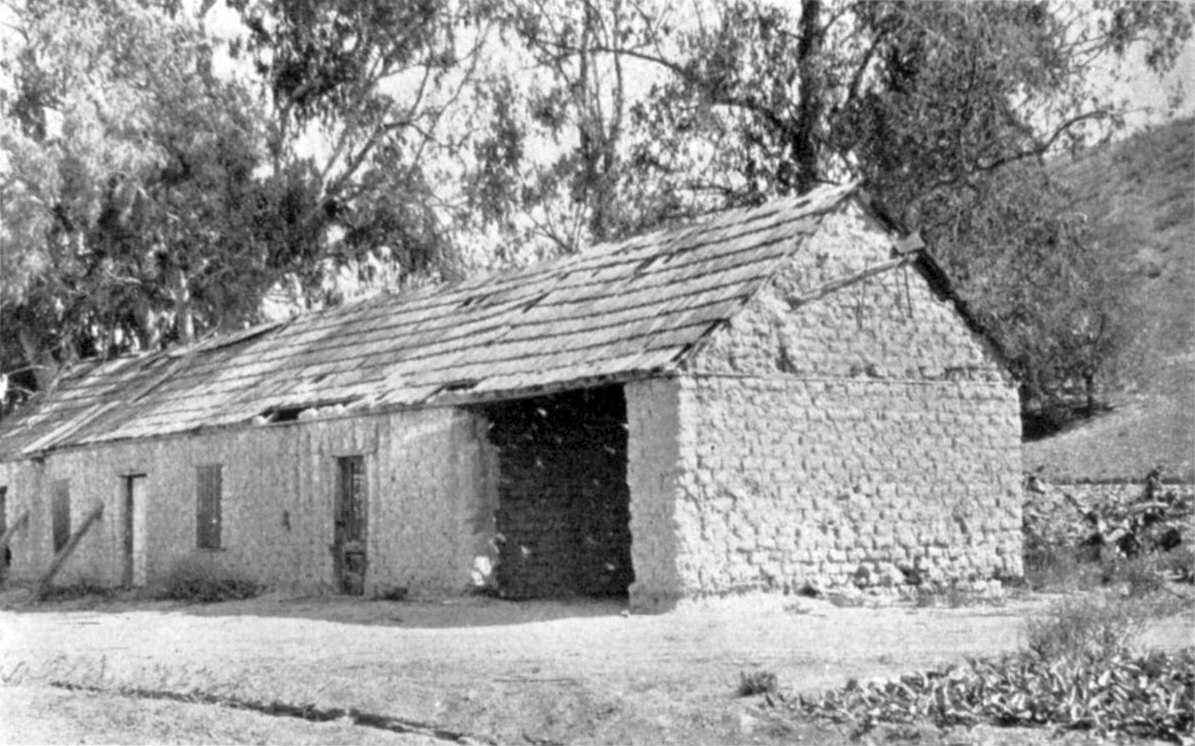

When the first United States surveying parties, under Beale and Ord and Hancock, inscribed old place names on the fresh paper of new maps, and resorted to imagination in the matter of spelling where they did not know their Spanish, there was some excuse, for of the entire population of Los Angeles County in 1850, only 616 out of 1734 adults could read and write. But curious perversions with less warrant have occurred in the making of more recent maps. One of them survives in the well-known name of "Bouquet Cañon." Its story was told me by José Jesus Lopez of Rancho El Tejon. In days when the Rancho of Chico Lopez was at its height, the handsome ranchero pastured his horses there, and the cañon was known as "El Potrero" (the pasture) for short, or "El Potrero de Chico Lopez," when one wanted to be explicit. By and by, when homesteaders and settlers began sifting in, not by twos and threes now, but in numbers, after the new railroad across the continent made travel easy [1870s — Ed.], Don Chico could foresee what was coming. He realized that even the range was no longer free for a man's stock to roam upon. He went to one of his men, Francisco Chari. "Francisco," he said, "no quieres un rancho? You ought to take up some land before the settlers come in and claim everything. Locate on the Potrero, then if you don't wish to keep it, I will buy it back from you later." Thus the Potrero became the rancho of this second Francisco. He was a Frenchman, a sailor who had settled in California and turned vaquero. In the evenings around the camp fire he was forever harking back. to his sailor days, telling endless yarns of adventure on the seas, and tales of his buque, or ship, how he managed this buque, where he sailed in that one, until the Californios nicknamed him with the recurrent theme of his talk, "El Buque." So everyone knew the cañon where he settled under the patronage of Don Chico, who later became his father-in-law, as "El Rancho del Buque." Out of this some map-maker managed to contrive the meaningless "Bouquet!" There was no road through the cañon in those times, just a little-traveled trail, for all regular traffic between Los Angeles and points north passed through the more direct, though steeper, San Francisquito Cañon to the west. Martin Ruiz, a Spaniard of light complexion who used to live in San Fernando, was the first to locate on the good grazing land at the outlet of San Francisquito and "Bouquet" Cañons, where they emerge in the vicinity of present-day Saugus. At the mouth of the old San Francisquito road he settled, in a place which was then known as "El Cañon de los Muertos," or "Dead Man's Cañon," by those who spoke English. Long before, it had been called "La Canada del Agua Dulce." It became Cañon de los Muertos in the days of Don Ygnacio Del Valle, who was nicknamed Pacacho, because of his small stature, when a battle took place there from which at least one rustler had not emerged alive. Retreating to the little side cañon with a band of horses stolen from the Del Valle's Rancho San Francisco, the bandits were pursued by Pacacho at the head of a motley company. Pacacho was armed with a rifle. A vaquero had a shotgun, someone had a pistol, and there were a few Indian retainers, armed with California lances, or lacking these, bows and arrows. The pursuit was determined, for at the Rancho a little boy mourned for his big old white horse, which had been driven off by the rustlers. This little boy grew up to be Senator Reginaldo del Valle. His uncle Pacacho restored his horse that day. Ruiz had a numerous family, and his sons established other adobe homes in the neighborhood. Quite a group of buildings were erected at the little settlement past which ran the stage and hauling road through San Francisquito Cañon. No less than seven of these buildings were swept away like so many toy houses in the Gargantuan flood released by the collapse of the St. Francis Dam half a century afterwards. Casa de Martin Ruiz At least one house that Martin Ruiz erected is still standing, however [in 1929 — Ed.], a mile or two up "El Cañon del Buque," facing west, at a point where the cañon widens out into a little desert valley, hemmed in by low hills. It is a long, rambling building, with rough brown walls of adobe brick that have never been plastered. The east wall of the cañon ascends rather abruptly behind it, still wild, covered with sagebrush and greasewood and manzanita, out of which rises grotesquely the angular and unpoetic form of a modern frame house which looks down disdainfully from across the road upon the abandoned adobe. Westward the adobe looks out across a wide flat, on which it is situated, toward low, rolling hills. The modern road runs between the two houses, scarcely ten feet from the back door of the adobe, and elevated upon an embankment level with its broken old eaves. Dust dry, after a protracted series of dry years have insidiously sucked out the moisture from everything in the cañon, it is hard to believe that the family who have owned the house since Martin Ruiz sold it to them in 1874, were forced to move out a few years ago because of periodical rising of the winter stream, flooding the field and the house and weakening its walls. It is a one-story adobe, generously proportioned, with adobe bricks built up nearly to the peak of its gabled roof. The hand-split shakes on it are original. All the lumber in the building came from Acton, and was hauled into the cañon with teams. Formerly a little ell extended to the rear at the north end of the house and was used as a kitchen. A shapeless pile and bit of crumbling wall mark this place, where stood the only fireplace in the house. Over it, built into the wall, was the oven. Once a corredor shaded the west front from the afternoon sun, but it has now quite disappeared. The walls are weathering badly, as the roof gradually decays and the eaves no longer afford adequate protection, so that the days of Martin Ruiz's adobe, last of its kind in romantic Cañon del Buque, seem inescapably numbered. Built in the later adobe period, the walls of this house are not as thick and sturdy as those of earlier structures. In 1874 Martin Ruiz sold the adobe and part of his rancho to the founder of an Italian family by whom it has been occupied ever since. Batista Suraco was a Genoan. Lured by dreams of California gold, he came here in 1859, when he was just 20 years of age. First trying his luck at Placerita Cañon, a few miles below "Bouquet" in '74 he bought the Ruiz adobe with the ambition of mining in Cañon del Buque. Fondly for 15 years he held to his dream of going home to Italy rich with gold taken out of those hills. Then he gave it up, turned to sheep ranching, and lived out his life in the adobe of Martin Ruiz. There J. Antonio Suraco, his son, was born, in 1876. Vivid are his recollections of his boyhood in Cañon del Buque. "There were so few people here then," he says. "We never saw anybody. Once a year maybe someone would come on horseback. My little sister and I would be afraid of the strange people, and we would run and hide under the bed. No matter what time they stopped my mother would cook for them. "During my early years the bandit Vasquez used to go by here. He had a spring up above in the mountains where he used to hide, and sometimes he camped under the big sycamore that stood not far from the adobe. "They used to steal cattle and drive them by here. We would hear them in the night, being herded north into the Sierras de Chico Lopez, as we used to call the hills. Now they are called Sierra Pelona, which means bald. The bandits never bothered my mother. Probably she fed many of them when they stopped at our house in the day time. There was a dug well here, with a windlass, and people who went by stopped for water. "But when my father was away, my mother was afraid. All the windows of our adobe had wooden shutters that locked from the inside. Every night when Father was gone she got us all inside and locked every one of them, at six o'clock, when darkness began to fall. Sometimes she would hear people outside in the night, stopping clandestinely to draw water up from the well. But then she would never let them in. "My father was a Genoan. They call them the Jews of Italy. He could not speak English very well, and at the age of fifteen I did all his business in town and with the banks. The Italians are sometimes afraid of a bank, and keep their money hidden at home. A friend of mine found $200 hidden in his father's old adobe in San Francisquito Cañon, behind one of the bricks. "In the old days there were many bears here. When my father first came he saw numerous trails that they had worn through the hills. Now the deer still come down to the reservoir to drink, more than ever of late years, since the dry seasons have dried up the springs in the mountains." Time and weather-worn as the old adobe is, with its sagging ridge pole and drooping roof, its empty rooms and shutterless windows, its decrepit walls, yielding under the heavy hand of age, there is a harmony between it and the surrounding landscape such as its nearby frame neighbor never can achieve, however many coats of fresh paint it may acquire, whatever geometric elegance it may possess. I could picture it at night, in those days when Vasquez was the terror of the state, out there in the desolate cañon, quite alone under the dark sky, with perhaps the lonesome small light of a candle gleaming at a shutter's edge, and a coyote wailing in the black hills.

Download full pdf here.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.