Gillibrand Titanium Mining Plans

Angeles National Forest, Lang-Sand Canyon Area

|

April 11, 1987 —

P.W. Gillibrand Company officials lead state and local political representatives, neighboring homeowners and members of the press on a helicopter tour of the 400 acres of the Angeles National Forest south of

Lang and east of Sand Canyon where they plan to mine ilmenite, a titanium-bearing ore. At the time, Gillibrand had already been mining sand and gravel in Soledad Canyon for 20 years.

According to the federal Environmental Impact Statement approved in 1991, the new mining operation would extract up to 400,000 tons of ilmenite and an additional 954,000 tons of sand and gravel annually.

Any active mining shown in the photos above is the preexisting sand and gravel operation. The man with one leg is Phil Gillibrand. The woman sanding next to the big mining truck is Julie Justus,

representing U.S. Sen. Pete Wilson. In the group photos, the woman

with dark, curly hair is Jo Anne Darcy, field deputy to Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich. The City of Santa Clarita does not yet exist. The houses in closeups — from which many of the complaints

emanated — are located on the east side of Sand Canyon Road just south of the Placerita intersection.

Photos by Gary Thornhill/The Signal.

2 Strip Mines in Angeles Forest?

Mining Plans Irk Neighbors.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Sunday, April 5, 1987.

Click to enlarge.

|

Trucks laden with titanium and magnetite ore may soon be rumbling out of the Angeles National Forest, where two strip mining operations are planned.

An "open pit" operation, the Black Diamond Mine, proposed for a site across from the Live Oak campground in Sand Canyon, has canyon residents gearing up for a fight.

And Phil Gillibrand, a Simi Valley sand and gravel supplier, wants to remove 40,000 tons of ore samples for a future mining operation between Lang Station and Magic Mountain (the hill, not the amusement park. See map.)

At the Black Diamond Mine, "they'll bulldoze the ore down the canyon and into a crusher," said Steve Bear, resource officer for the Tujunga Ranger District of the U.S. Forest Service.

United General Corp. will truck the magnetite (iron) ore from its mine down Sand Canyon Road to an undisclosed cement plant, Bear said.

Sand Canyon residents, who learned only recently of the plans, complained that they have had no input into an environmental report on the Black Diamond Mine. They said they were told by the Forest Service the report could be completed and mining operations begun without public input.

Expensive canyon homes lie within about 300 yards of the proposed mine site and Crystal Springs Ranch residents fear the noise and destruction of hillsides from the mining operation.

"That this could go on in an urban area without the public knowing about it is amazing," Sand Canyon resident Jan Heidt said.

A group of canyon residents, "Minebusters," headed by Mike Levison, is gathering a war chest to fight the mining operation in court.

Curtis Bianchi, president of the Sand Canyon Homeowners Association, said yesterday the group will battle to keep the mine out of the canyon.

But the right to make mining claims on the forest land, established by law in 1872, provides strong protections for the miners. The federal law has been challenged and upheld.

Although the Minebusters' "opinion is valid," said Bear, once miners document the deposits present and file a claim, little can be done to stop them from mining. "The Forest Service has to provide access to them."

The typical claim encompasses some 20 acres; the Black Diamond Mine is on two claim sites, covering about 40 acres. Following completion of an environmental report, the mine could be in operation by the end of the year.

The mining operation has been in the works since 1982 but the latest environmental work by United General caught residents by surprise. They vowed to pressure the Forest Service to conduct a public hearing on the proposal.

A hearing will be held on the Gillibrand Co. mining operation and its 11.4 miles of pioneer road construction work planned north of Magic Mountain.

Gillibrand has 400 mining claims on more than 8,000 acres of national forest land but is presently exploring titanium deposits on only 10 claims. Open-pit mining will be used.

"They're a long way from any homes or people," Gillibrand said Friday.

Once the mining work is completed, Gillibrand must reseed the hillsides with chaparral and replace trees. Barren hillsides might be cut with terraces, with vegetation planted in the flatter areas.

In Gillibrand's timetable, the bulk of the ore would be excavated and transported this year, his "rehabilitation work" would begin in July 1988 and be completed "in 50 years, more or less," by 2038.

Gillibrand, who has a mining operation near Lang Station, was enthusuastic about the titanium deposits found at several of the claims.

"This could be one of the largest deposits in the United States," he said.

Titanium is currently being used as a replacement for lead in paint and in construction in the aerospace industry. The thin white coating on some prescription pills is a titanium oxide.

Residents are concerned that the pioneer roads into the forest area will open it up to off-road vehicles. And they fear the effect of the mining operation on stream channels draining through Oak Spring Canyon.

"They will not open the road to the public and there is no back way access," Gillibrand said. "The roads are hidden from sight."

Access will be controlled with locked gates, Forest Service officials said.

The new access roads would eventually be increased to a permanent 16-foot-wide single-lane road with turnouts.

An environmental assessment of the effect on stream drainage says the impact of the mining would be difficult to predict. Sediments flowing from Oak Spring Canyon could increase from the mining operation.

"Typical damage could consist of scour or filling of the stream channel with sediments, and vegetation damage," a geohydrology report on the proposal states. "The excavation of the alluvial sediments could change the local groundwater flow pattern."

|

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

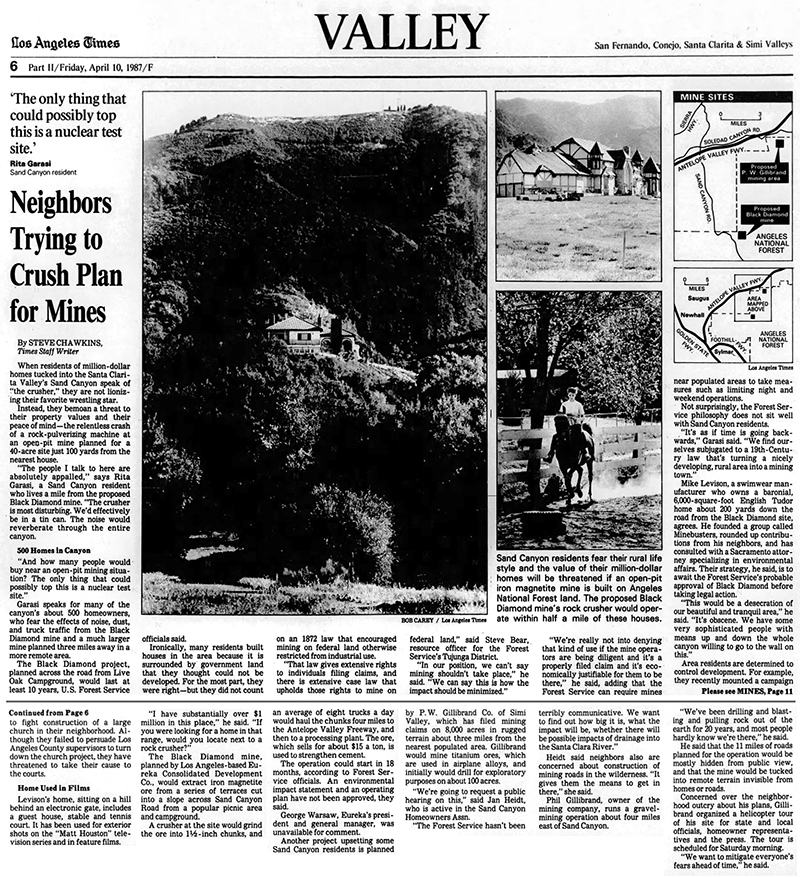

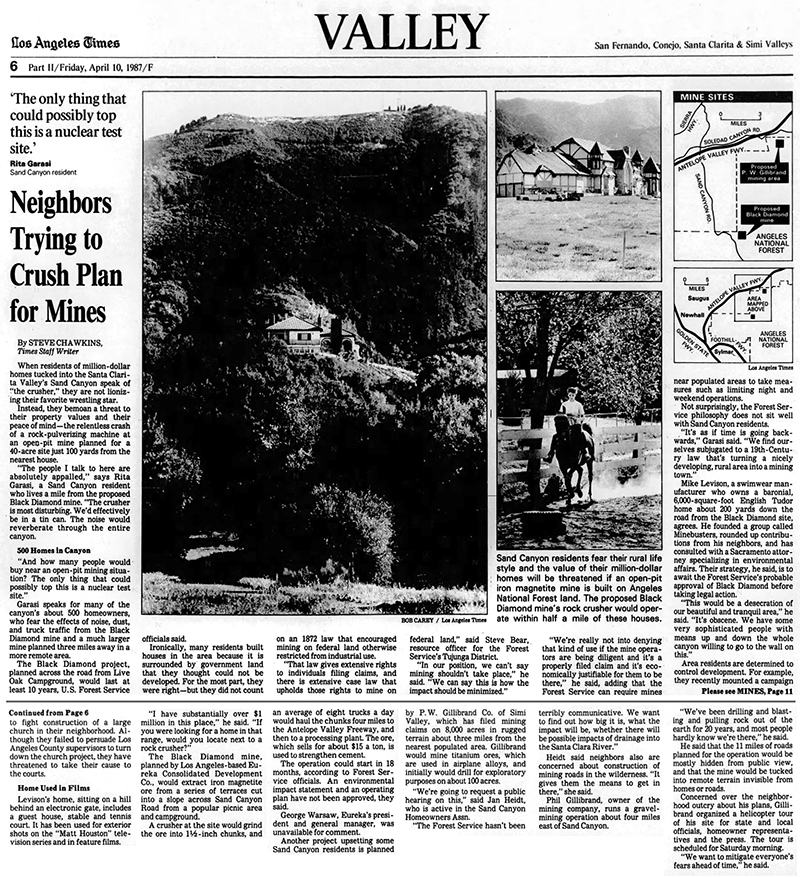

Neighbors Trying to Crush Plan for Mines.

Los Angeles Times | Friday, April 10, 1987.

When residents of million-dollar homes tucked into the Santa Clarita Valley's Sand Canyon speak of "the crusher," they are not lionizing their favorite wrestling star.

Instead, they bemoan a threat to their property values and their peace of mind — the relentless crash of a rock-pulverizing machine at an open-pit mine planned for a 40-acre site just 100 yards from the nearest house.

"The people I talk to here are absolutely appalled," says Rita Garasi, a Sand Canyon resident who lives a mile from the proposed Black Diamond mine. "The crusher is most disturbing. We'd effectively be in a tin can. The noise would reverberate through the entire canyon.

"And how many people would buy near an open-pit mining situation? The only thing that could possibly top this is a nuclear test site."

Garasi speaks for many of the canyon's about 500 homeowners, who fear the effects of noise, dust, and truck traffic from the Black Diamond mine and a much larger mine planned three miles away in a more remote area.

The Black Diamond project, planned across the road from Live Oak Campground, would last at least 10 years, U.S. Forest Service officials said.

Ironically, many residents built houses in the area because it is surrounded by government land that they thought could not be developed. For the most part, they were right — but they did not count on an 1872 law that encouraged mining on federal land otherwise restricted from industrial use.

"That law gives extensive rights to individuals filing claims, and there is extensive case law that upholds those rights to mine on federal land," said Steve Bear, resource officer for the Forest Service's Tujunga District.

"In our position, we can't say mining shouldn't take place," he said. "We can say this is how the impact should be minimized."

"We're really not into denying that kind of use if the mine operators are being diligent and it's a properly filed claim and it's economically justifiable for them to be there," he said, adding that the Forest Service can require mines near populated areas to take measures such as limiting night and weekend operations.

Not surprisingly, the Forest Service philosophy does not sit well with Sand Canyon residents.

"It's as if time is going backwards," Garasi said. "We find ourselves subjugated to a 19th-century law that's turning a nicely developing, rural area into a mining town."

Mike Levison, a swimwear manufacturer who owns a baronial, 6,000-square-foot English Tudor home about 200 yards down the road from the Black Diamond site, agrees. He founded a group called Minebusters, rounded up contributions from his neighbors, and has consulted with a Sacramento attorney specializing in environmental affairs. Their strategy, he said, is to await the Forest Service's probable approval of Black Diamond before taking legal action.

"This would be a desecration of our beautiful and tranquil area," he said. "It's obscene. We have some very sophisticated people with means up and down the whole canyon willing to go to the wall on this."

Area residents are determined to control development. For example, they recently mounted a campaign to fight construction of a large church in their neighborhood. Although they failed to persuade Los Angeles County supervisors to turn down the church project, they have threatened to take their cause to the courts.

Levison's home, sitting on a hill behind an electronic gate, includes a guest house, stable and tennis court. It has been used for exterior shots on the "Matt Houston" television series and in feature films.

"I have substantially over $1 million in this place," he said. "If you were looking for a home in that range, would you locate next to a rock crusher?"

The Black Diamond mine, planned by Los Angeles-based Eureka Consolidated Development Co., would extract iron magnetite ore from a series of terraces cut into a slope across Sand Canyon Road from a popular picnic area and campground.

A crusher at the site would grind the ore into 1½-inch chunks, and an average of eight trucks a day would haul the chunks four miles to the Antelope Valley Freeway, and then to a processing plant. The ore, which sells for about $15 a ton, is used to strengthen cement.

The operation could start in 18 months, according to Forest Service officials. An environmental impact statement and an operating plan have not been approved, they said.

George Warsaw, Eureka's president and general manager, was unavailable for comment.

Another project upsetting some Sand Canyon residents is planned by P.W. Gillibrand Co. of Simi Valley, which has filed mining claims on 8,000 acres in rugged terrain about three miles from the nearest populated area. Gillibrand would mine titanium ores, which are used in airplane alloys, and initially would drill for exploratory purposes on about 100 acres.

"We're going to request a public hearing on this," said Jan Heidt, who is active in the Sand Canyon Homeowners Assn.

"The Forest Service hasn't been terribly communicative. We want to find out how big it is, what the impact will be, whether there will be possible impacts of drainage into the Santa Clara River."

Heidt said neighbors also are concerned about construction of mining roads in the wilderness. "It gives them the means to get in there," she said.

Phil Gillibrand, owner of the mining company, runs a gravel-mining operation about four miles east of Sand Canyon.

"We've been drilling and blasting and pulling rock out of the earth for 20 years, and most people hardly know we're there," he said.

He said that the 11 miles of roads planned for the operation would be mostly hidden from public view, and that the mine would be tucked into remote terrain invisible from homes or roads.

Concerned over the neighborhood outcry about his plans, Gillibrand organized a helicopter tour of his site for state and local officials, homeowner representatives and the press. The tour is scheduled for Saturday morning.

"We want to mitigate everyone's fears ahead of time," he said.

|

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

Miner Hopes for a Heavy Load.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Sunday, April 12, 1987.

The developer of proposed titanium mines in Sand Canyon took neighbors, government officials, and press on a tour yesterday.

P.W. Gillibrand hoped to convince the group, and especially complaining neighbors, that his plans to engage in strip mining in the area will do no environmental harm.

He took them up in two helicopters that alternately flew above ridges and descended below them to dramatize the view. From time to time the copters settles down and the tour continued on the ground.

Gillibrand officials and their consultants, meanwhile, told their guests that their proposed tungsten mines on the ridges east of Sand Canyon will have minimal visual impact on the exclusive Sand Canyon neighborhood.

"We want your support," said Gillibrand. We want to be a credit to your community. This area will be a showplace."

But several nearby homeowners were openly skeptical, complaining their quiet oak studded neighborhoods were incompatible with open-pit mining.

"I thought the forest was intended to be a place for kids and a nice place to visit, not commercial uses," said Crystal Springs Ranch resident George Thomas.

"This is the closest national forest to the Santa Clarita Valley. It seems that oak trees are more important than sand and gravel."

Jess Barton, Gillibrand's environmental consultant and Tujunga district ranger when Gillibrand first began gravel mining in Soledad Canyon in 1968, rebutted that national forests are managed for a variety of uses.

"Gillibrand is a good neighbor," said Barton. "Most of what will occur will be very temporary."

Barton said that oak trees will be replaced and natural vegetation replanted once the valuable minerals are removed.

Pointing to a fence that marks the forest boundary line, Gillibrand said the county has a responsibility to protect his mining operation from urban encroachment.

Erica Betz of Crystal Springs Ranch said her family and neighbors will go to court if necessary to stop the mining operation.

"The safety and peacefulness of our neighborhood means a lot to us," said Betz.

Gillibrand's technical director, John Heter, pointed out differences between the proposed Black Diamond titanium mine in Sand Canyon and Gillibrand's proposed operations.

Unlike Black Diamond, whose trucks would use narrow and congested two-lane streets through residential neighborhoods, Gillibrand, Heter said, would operate in the mountains behind locked gates.

The minerals would be shipped to market by an adjacent rail line or by trucks which enter Highway 14 from just outside Gillibrand's plant on Lang Station Road, he added.

Although Gillibrand has 562 milling claims covering over 10,000 acres in the forest, Heter said surface disturbance would be minimal because it is economical to mine only a few acres at a time.

Helicopter tours of proposed titanium mining areas were used in an attempt to prove Heter's argument that the strip mining's impact on the Sand Canyon view would be minimal.

Gillibrand is currently building roads to several of the claims in order that open-pit ore sampling may be done.

According to an environmental assessment prepared by Gillibrand, the object of the current exploratory work is to remove about 40,000 tons of ore in hopes of proving the project's economic feasibility and to secure additional investors.

An environmental impact statement, a public hearing, and Forest Service approval would be required before a full-scale mining operation could begin.

Although Gillibrand currently pays the federal government royalties for sand and gravel he removes from forest lands, he would not pay royalties on the titanium and associated minerals.

According to Jan Pedrosian of the Bureau of Land Management, this is because titanium is classified as a "locatable mineral" and the government wishes to encourage the costly and highly speculative search for locatable mineral deposits.

|

'Largest Titanium Find in the United States.'

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Sunday, April 12, 1987.

Phil Gillibrand is bullish on titanium.

He says his planned Soledad Canyon titanium mines will exploit what is possibly the largest titanium deposit in the continental United States.

"The company's 562 mining claims contain proven titanium reserves well in excess of 100 million tons and also contain other rare earth and elements," said Gillibrand.

The bulk of the titanium deposits are located several miles east of Gillibrand's sand and gravel operation and north of Magic Mountain (the peak, not the amusement park) in 1.5-billion-year-old Pre-Cambrian deposits.

It will be a fairly simple matter to truck the valuable ore down to his processing plant, said Gillibrand, and then load the processed titanium onto ore cars on an adjacent railroad line or on trucks for shipment to Los Angeles harbor und other points.

"Scientists generally agree titanium will succeed copper and iron to become the third most important metal for industry in the next century," said minerals expert Ward Minkler recently.

Titanium's resistance to corrosion, high tensile strength, ability to withstand extreme chances in temperature, and light weight is being utilized in a variety of industries.

Titanium's primary use is as a replacement for lead in paint, but it is also used in welding, aircraft components, plastic fillers, creating smokescreen chemicals, and shipboard pumps.

Much of the titanium is expected to go to Southern California military subcontractors.

Because of its many defense-related applications, titanium has been classified by the federal government as a strategic mineral.

Tim Krantz, who wrote the environmental report on Gillibrand's projected mine, said, "This kind of claim is supposed to be reviewed in the light that it is of greater significance."

However, Bob Anderson, Deputy State Director of Mineral Resources for the Bureau of Land Management, which will oversee Gillibrand's proposed mining, said titanium mines are not given special priority.

"Just because a mineral is strategic or critical doesn't give it any special status," said Anderson.

Gillibrand's financial planner, Don Blubaugh, said exports of Gillibrand's titanium could help solve the country's ever-worsening balance of trade.

He said the U.S. was an exporter of titanium several decades ago, but now we import about 75 percent of our raw titanium.

Blubaugh also noted that productlion of magnetite, which is used in cement-making, will be done concurrently with titanium and fill a void created when Kaiser Steel closed their Fontana plant.

"We're kind of looking at the salvation of the California cement industry here," said Blubaugh.

Gillibrand, who has been in business in Soledad Canyon for 20 years as a producer of construction materials and industrial sands, will also market the sand and gravel removed in digging for the titanium ore.

Said Blubaugh, "Sand and gravel is our bread and butter and once in a while — with titanium — you get a little caviar."

|

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

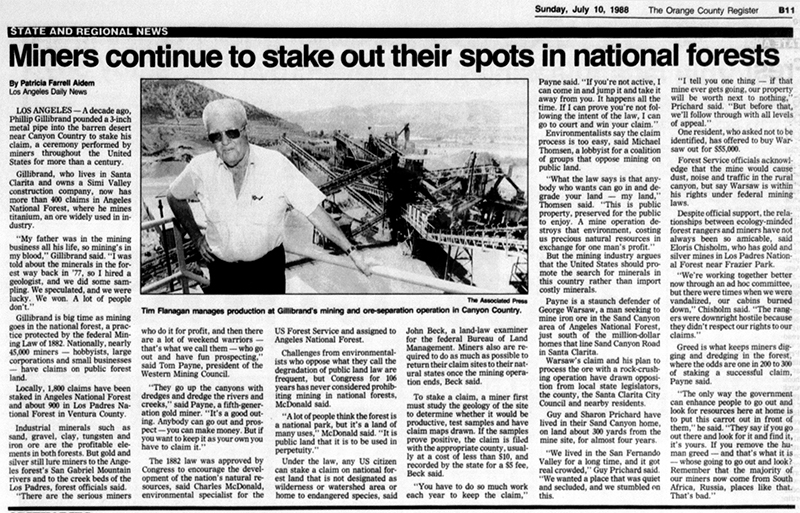

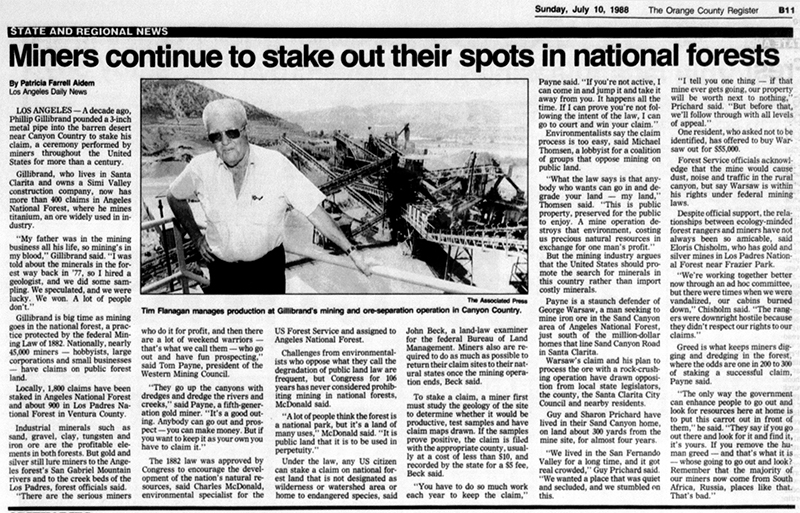

Miners Continue to Stake Out Their Spots in National Forests.

By Patricia Farrell Aidem

Los Angeles Daily News | As published in the Orange County Register, Sunday, July 10, 1988.

Los Angeles — A decade ago, Phillip Gillibrand pounded a 3-inch metal pipe into the barren desert near Canyon Country to stake his claim, a ceremony performed by miners throughout the United States for more than a century.

Gillibrand, who lives in Santa Clarita and owns a Simi Valley construction company, now has more than 400 claims in Angeles National Forest, where he mines titanium, an ore widely used in industry.

"My father was in the mining business all his life, so mining's in my blood," Gillibrand said. "I was told about the minerals in the forest way back in '77, so I hired a geologist, and we did some sampling. We speculated, and we were lucky. We won. A lot of people don't."

Gillibrand is big time as mining goes in the national forest, a practice protected by the federal Mining Law of 1882. Nationally, nearly 45,000 miners — hobbyists, large corporations and small businesses — have claims on public forest land.

Locally, 1,800 claims have been staked in Angeles National Forest and about 400 in Los Padres National Forest in Ventura County.

Industrial minerals such as sand, gravel, clay, tungsten and iron ore are the profitable elements in both forests. But gold and silver still lure miners to the Angeles Forest's San Gabriel Mountain rivers and to the creek beds of the Los Padres, forest officials said.

"There are the serious miners who do it for profit, and then there are a lot of weekend warriors — that's what we call them — who go out and have fun prospecting," said Tom Payne, president of the Western Mining Council.

"They go up the canyons with dredges and dredge the rivers and creeks," said Payne, a fifth-generation gold miner. "It's a good outing. Anybody can go out and prospect — you can make money. But if you want to keep it as your own you have to claim it."

The 1882 law was approved by Congress to encourage the development of the nation's natural resources, said Charles McDonald, environmental specialist for the U.S. Forest Service and assigned to Angeles National Forest.

Challenges from environmentalists who oppose what they call the degradation of public land law are frequent, but Congress for 106 years has never considered prohibiting mining in national forests, McDonald said.

"A lot of people think the forest is a national park, but it's a land of many uses," McDonald said. "It is public land that it is to be used in perpetuity."

Under the law, any U.S. citizen can stake a claim on national forest land that is not designated as wilderness or watershed area or home to endangered species, said John Beck, a land-law examiner for the federal Bureau of Land Management. Miners also are required to do as much as possible to return their claim sites to their natural states once the mining operation ends, Beck said.

To stake a claim, a miner first must study the geology of the site to determine whether it would be productive, test samples and have claim maps drawn. If the samples prove positive, the claim is filed with the appropriate county, usually at a cost of less than $10, and recorded by the state for a $5 fee, Beck said.

"You have to do so much work each year to keep the claim," Payne said. "If you're not active, I can come in and jump it and take it away from you. It happens all the time. If I can prove you're not following the intent of the law, I can go to court and win your claim.

Environmentalists say the claim process is too easy, said Michael Thomsen, a lobbyist for a coalition of groups that oppose mining on public land.

"What the law says is that anybody who wants can go in and degrade your land — my land," Thomsen said. "This is public property, preserved for the public to enjoy. A mine operation destroys that environment, costing us precious natural resources in exchange for one man's profit."

But the mining industry argues that the United States should promote the search for minerals in this country rather than import costly minerals.

Payne is a staunch defender of George Warsaw, a man seeking to mine iron ore in the Sand Canyon area of Angeles National Forest, just south of the million-dollar homes that line Sand Canyon Road in Santa Clarita.

Warsaw's claim and his plan to process the ore with a rock-crushing operation have drawn opposition from local state legislators, the county, the Santa Clarita City Council and nearby residents.

Guy and Sharon Prichard have lived in their Sand Canyon home, on land about 300 yards from the mine site, for almost four years.

"We lived in the San Fernando Valley for a long time, and it got real crowded," Guy Prichard said. "We wanted a place that was quiet and secluded, and we stumbled on this.

"I tell you one thing — if that mine ever gets going, our property will be worth next to nothing," Prichard said. "But before that, we'll follow through with all levels of appeal."

One resident, who asked not to be identified, has offered to buy Warsaw out for $55,000.

Forest Service officials acknowledge that the mine would cause dust, noise and traffic in the rural canyon, but say Warsaw is within his rights under federal mining laws.

Despite official support, the relationships between ecology-minded forest rangers and miners have not always been so amicable, said Eloris Chisholm, who has gold and silver mines in Los Padres National Forest near Frazier Park.

"We're working together better now through an ad hoc committee, but there were times when we were vandalized, our cabins burned down," Chisholm said. "The rangers were downright hostile because they didn't respect our rights to our claims."

Greed is what keeps miners digging and dredging in the forest, where the odds are one in 200 to 300 of staking a successful claim, Payne said.

"The only way the government can enhance people to go out and look for resources here at home is to put this carrot out in front of them," he said. "They say if you go out there and look for it and find it, it's yours. If you remove the human greed — and that's what it is — who's going to go out and look? Remember that the majority of our miners now come from South Africa, Russia, places like that. That's bad."

|

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

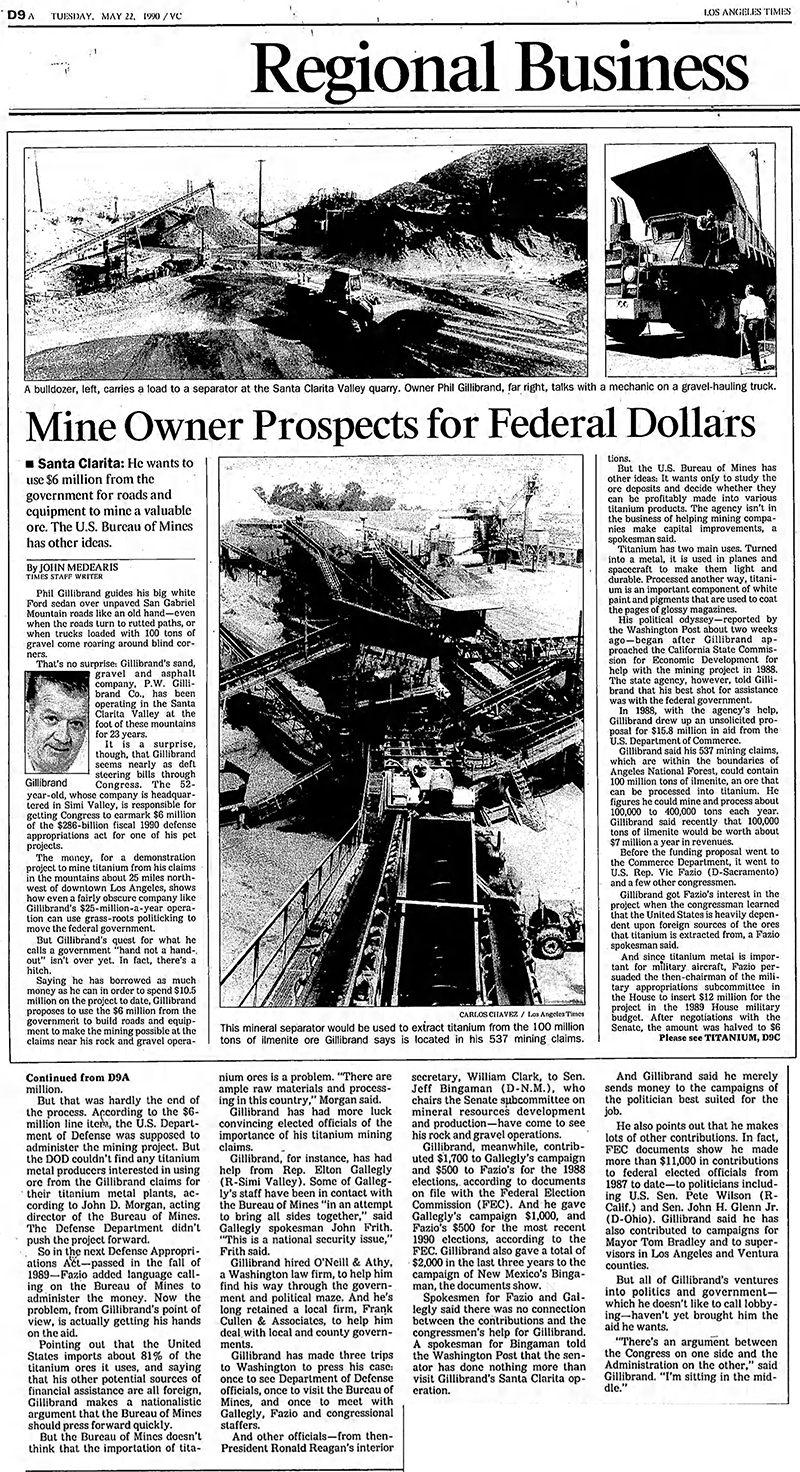

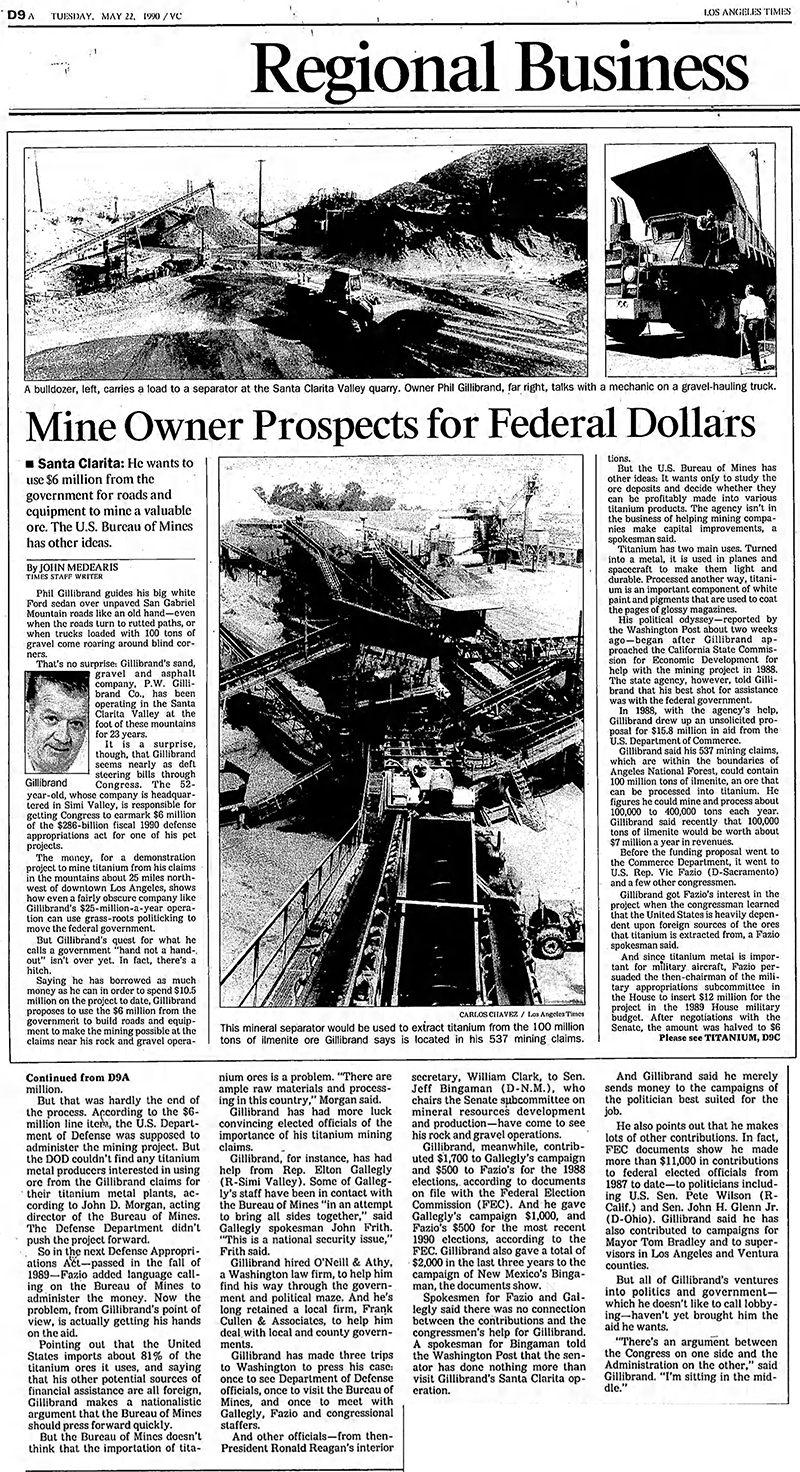

Mine Owner Prospects for Federal Dollars.

Santa Clarita: He wants to use $6 million from the government for roads and equipment to mine a valuable ore. The U.S. Bureau of Mines has other ideas.

Los Angeles Times | May 22, 1990.

Phil Gillibrand guides his big white Ford sedan over unpaved San Gabriel Mountain roads like an old hand — even when the roads turn to rutted paths, or when trucks loaded with 100 tons of gravel come roaring around blind corners.

That's no surprise: Gillibrand's sand, gravel and asphalt company, P.W. Gillibrand Co., has been operating in the Santa Clarita Valley at the foot of these mountains for 23 years.

It is a surprise, though, that Gillibrand seems nearly as deft steering bills through Congress. The 52-year-old, whose company is headquartered in Simi Valley, is responsible for getting Congress to earmark $6 million of the $286-billion fiscal 1990 defense appropriations act for one of his pet projects.

The money, for a demonstration project to mine titanium from his claims in the mountains about 25 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles, shows how even a fairly obscure company like Gillibrand's $25-million-a-year operation can use grass-roots politicking to move the federal government.

But Gillibrand's quest for what he calls a government "hand not a hand-out" isn't over yet. In fact, there's a hitch.

Saying he has borrowed as much money as he can in order to spend $10.5 million on the project to date, Gillibrand proposes to use the $6 million from the government to build roads and equipment to make the mining possible at the claims near his rock and gravel operations.

But the U.S. Bureau of Mines has other ideas: It wants only to study the ore deposits and decide whether they can be profitably made into various titanium products. The agency isn't in the business of helping mining companies make capital improvements, a spokesman said.

Titanium has two main uses. Turned into a metal, it is used in planes and spacecraft to make them light and durable. Processed another way, titanium is an important component of white paint and pigments that are used to coat the pages of glossy magazines.

His political odyssey — reported by the Washington Post about two weeks ago — began after Gillibrand approached the California State Commission for Economic Development for help with the mining project in 1988. The state agency, however, told Gillibrand that his best shot for assistance was with the federal government.

In 1988, with the agency's help, Gillibrand drew up an unsolicited proposal for $15.8 million in aid from the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Gillibrand said his 537 mining claims, which are within the boundaries of Angeles National Forest, could contain 100 million tons of ilmenite, an ore that can be processed into titanium. He figures he could mine and process about 100,000 to 400,000 tons each year. Gillibrand said recently that 100,000 tons of ilmenite would be worth about $7 million a year in revenues.

Before the funding proposal went to the Commerce Department, it went to U.S. Rep. Vic Fazio (D-Sacramento) and a few other congressmen.

Gillibrand got Fazio's interest in the project when the congressman learned that the United States is heavily dependent upon foreign sources of the ores that titanium is extracted from, a Fazio spokesman said.

And since titanium metal is important for military aircraft, Fazio persuaded the then-chairman of the military appropriations subcommittee in the House to insert $12 million for the project in the 1989 House military budget. After negotiations with the Senate, the amount was halved to $6 million.

But that was hardly the end of the process. According to the $6-million line item, the U.S. Department of Defense was supposed to administer the mining project. But the DOD couldn't find any titanium metal producers interested in using ore from the Gillibrand claims for their titanium metal plants, according to John D. Morgan, acting director of the Bureau of Mines. The Defense Department didn't push the project forward.

So in the next Defense Appropriations Act — passed in the fall of 1989 — Fazio added language calling on the Bureau of Mines to administer the money. Now the problem, from Gillibrand's point of view, is actually getting his hands on the aid.

Pointing out that the United States imports about 81 percent of the titanium ores it uses, and saying that his other potential sources of financial assistance are all foreign, Gillibrand makes a nationalistic argument that the Bureau of Mines should press forward quickly.

But the Bureau of Mines doesn't think that the importation of titanium ores is a problem. "There are ample raw materials and processing in this country," Morgan said.

Gillibrand has had more luck convincing elected officials of the importance of his titanium mining claims.

Gillibrand, for instance, has had help from Rep. Elton Gallegly (R-Simi Valley). Some of Gallegly's staff have been in contact with the Bureau of Mines "in an attempt to bring all sides together," said Gallegly spokesman John Frith. "This is a national security issue," Frith said.

Gillibrand hired O'Neill & Athy, a Washington law firm, to help him find his way through the government and political maze. And he's long retained a local firm, Frank Cullen & Associates, to help him deal with local and county governments.

Gillibrand has made three trips to Washington to press his case: once to see Department of Defense officials, once to visit the Bureau of Mines, and once to meet with Gallegly, Fazio and congressional staffers.

And other officials — from then-President Ronald Reagan's interior secretary, William Clark, to Sen. Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.), who chairs the Senate subcommittee on mineral resources development and production — have come to see his rock and gravel operations.

Gillibrand, meanwhile, contributed $1,700 to Gallegly's campaign and $500 to Fazio's for the 1988 elections, according to documents on file with the Federal Election Commission (FEC). And he gave Gallegly's campaign $1,000, and Fazio's $500 for the most recent 1990 elections, according to the FEC. Gillibrand also gave a total of $2,000 in the last three years to the campaign of New Mexico's Bingaman, the documents show.

Spokesmen for Fazio and Gallegly said there was no connection between the contributions and the congressmen's help for Gillibrand. A spokesman for Bingaman told the Washington Post that the senator has done nothing more than visit Gillibrand's Santa Clarita operation.

And Gillibrand said he merely sends money to the campaigns of the politician best suited for the job.

He also points out that he makes lots of other contributions. In fact, FEC documents show he made more than $11,000 in contributions to federal elected officials from 1987 to date — to politicians including U.S. Sen. Pete Wilson (R-Calif.) and Sen. John H. Glenn Jr. (D-Ohio). Gillibrand said he has also contributed to campaigns for Mayor Tom Bradley and to supervisors in Los Angeles and Ventura counties.

But all of Gillibrand's ventures into politics and government — which he doesn't like to call lobbying — haven't yet brought him the aid he wants.

"There's an argument between the Congress on one side and the Administration on the other," said Gillibrand. "I'm sitting in the middle."

|

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

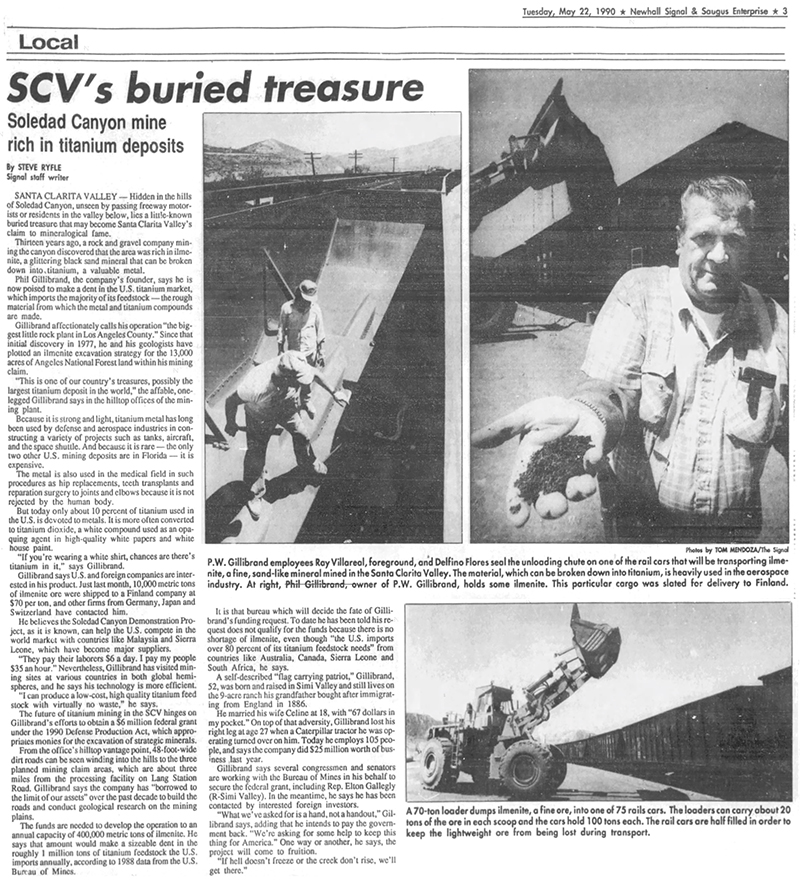

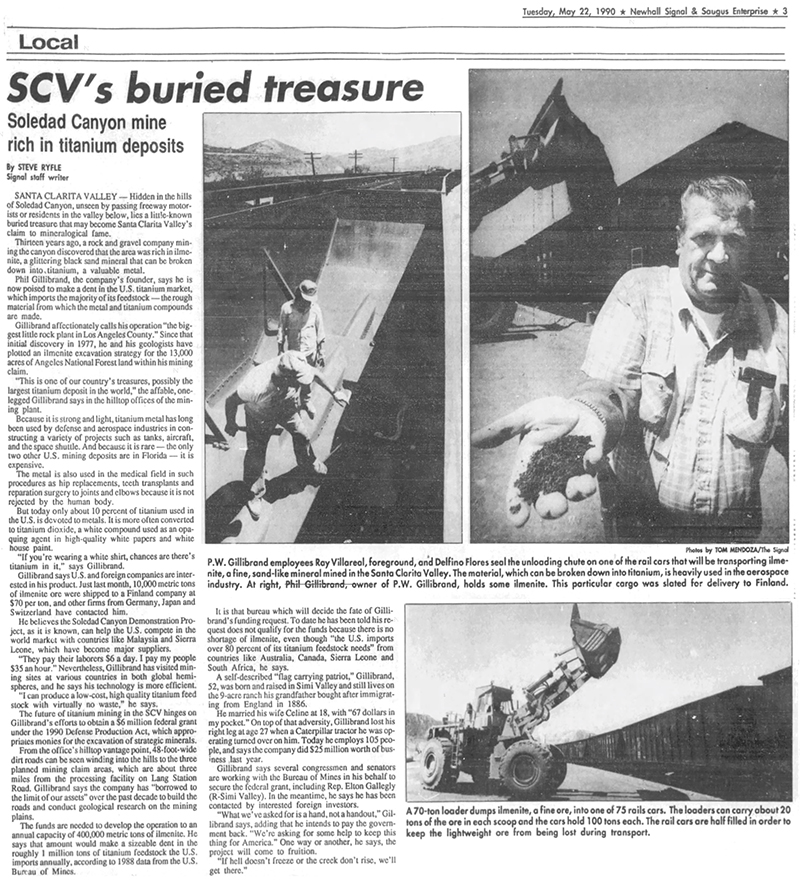

Soledad Canyon mine rich in titanium deposits.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Tuesday, May 22, 1990.

Santa Clarita Valley — Hidden in the hills of Soledad Canyon, unseen by passing freeway motorists or residents in the valley below, lies a little-known buried treasure that may become Santa Clarita Valley's claim to mineralogical fame.

Thirteen years ago, a rock and gravel company mining the canyon discovered that the area was rich in ilmenite, a glittering black sand mineral that can be broken down into titanium, a valuable metal.

Phil Gillibrand, the company's founder, says he is now poised to make a dent in the U.S. titanium market, which imports the majority of its feedstock — the rough material from which the metal and titanium compounds are made.

Gillibrand affectionately calls his operation "the biggest little rock plant in Los Angeles County." Since that initial discovery in 1977, he and his geologists have plotted an ilmenite excavation strategy for the 13,000 acres of Angeles National Forest land within his mining claim.

"This is one of our country's treasures, possibly the largest titanium deposit in the world," the affable, one-legged Gillibrand says in the hilltop offices of the mining plant.

Because it is strong and light, titanium metal has long been used by defense and aerospace industries in constructing a variety of projects such as tanks, aircraft, and the space shuttle. And because it is rare — the only two other U.S. mining deposits are in Florida — it is expensive.

The metal is also used in the medical field in such procedures as hip replacements, teeth transplants and reparation surgery to joints and elbows because it is not rejected by the human body.

But today only about 10 percent of titanium used in the U.S. is devoted to metals. It is more often converted to titanium dioxide, a white compound used as an opaquing agent in high-quality white papers and white house paint.

"If you're wearing a white shirt, chances are there's titanium in it," says Gillibrand.

Gillibrand says U.S. and foreign companies are interested in his product. Just last month, 10,000 metric tons of ilmenite ore were shipped to a Finland company at $70 per ton, and other firms from Germany, Japan and Switzerland have contacted him.

He believes the Soledad Canyon Demonstration Project, as it is known, can help the U.S. compete in the world market with countries like Malaysia and Sierra Leone, which have become major suppliers.

"They pay their laborers $6 a day. I pay my people $33 an hour." Nevertheless, Gillibrand has visited mining sites at various countries in both global hemispheres, and he says his technology is more efficient.

"I can produce a low-cost, high quality titanium feed stock with virtually no waste," he says.

The future of titanium mining in the SCV hinges on Gillibrand's efforts to obtain a $6 million federal grant under the 1990 Defense Production Act, which appropriates monies for the excavation of strategic minerals.

From the office's hilltop vantage point, 48-foot-wide dirt roads can be seen winding into the hills to the three planned mining claim areas, which are about three miles from the processing facility on Lang Station Road. Gillibrand says the company has "borrowed to the limit of our assets" over the past decade to build the roads and conduct geological research on the mining plains.

The funds are needed to develop the operation to an annual capacity of 400,000 metric tons of ilmenite. He says that amount would make a sizeable dent in the roughly 1 million tons of titanium feedstock the U.S. imports annually, according to 1988 data from the U.S. Bureau of Mines. [Note: According to the EIS, 400,000 tons of ilmenite and 954,000 tons of sand and gravel would be extracted annually. The previously mentioned 40,000 tons related to an exploratory project.]

It is that bureau which will decide the fate of Gillibrand's funding request. To date he has been told his request does not qualify for the funds because there is no shortage of ilmenite, even though "the U.S. imports over 80 percent of its titanium feedstock needs" from countries like Australia, Canada, Sierra Leone and South Africa, he says.

A self-described "flag carrying patriot," Gillibrand, 52, was born and raised in Simi Valley and still lives on the 9-acre ranch his grandfather bought after immigrating from England in 1886.

He married his wife Celine at 18, with "67 dollars in my pocket." On top of that adversity, Gillibrand lost his right leg at age 27 when a Caterpillar tractor he was operating turned over on him. Today he employs 105 people, and says the company did $25 million worth of business last year.

Gillibrand says several congressmen and senators are working with the Bureau of Mines in his behalf to secure the federal grant, including Rep. Elton Gallegly (R-Simi Valley). In the meantime, he says he has been contacted by interested foreign investors.

"What we've asked for is a hand, not a handout," Gillibrand says, adding that he intends to pay the government back. "We're asking for some help to keep this thing for America." One way or another, he says, the project will come to fruition.

"If hell doesn't freeze or the creek don't rise, we'll get there."

|

Soledad Canyon Mining Proposal Study Released.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Thursday, January 10, 1991.

Click to enlarge.

|

Canyon Country — A proposal to convert the hills of Soledad Canyon into a mining operation rich in materials precious to the defense and aerospace industries is being considered by federal officials.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on P.W. Gillibrand Co.'s proposal to mine titanium ores and related minerals on 780 acres of Angeles National Forest land has been distributed for public review. If approved, the project could put the Santa Clarita Valley on the mineralogical map.

Phil Gillibrand, founder of the rock and gravel company, discovered in 1977 that the area was rich in ilmenite, a glittering black sand mineral that can be broken down into titanium, a valuable metal.

Gillibrand now seeks to expand his operations into three planned mining claim areas, located about three miles from his mineral-processing facility on Lang Station Road.

Charlie McDonald, an environmental coordinator with the forest service, said the project presents no significant environmental impacts and within two to three years, a Plan of Operation dictating how the plant will be run will likely be approved.

"We've identified several issues, but most can be mitigated. We don't see any major problems," McDonald said.

"(Gillibrand) has claimed a large acreage, but the actual land that will be disturbed by this project is relatively small," McDonald said, adding that the project's effects will be similar to those of the existing sand and gravel mining.

A public meeting held last September was attended by representatives from three homeowners associations. According to the draft EIR, the closest homes to the project are in the Lost Canyon/Oak Creek community, about 3,300 feet west of a proposed truck road.

While the EIR states that "residents west and north of the project have expressed concern that the project will adversely affect local property values," McDonald and Gillibrand said no major objections were raised at the September meeting.

"We sent out about 300 notices, but only about 20 showed up," Gillibrand said. "There were no real objections, we were pleasantly surprised."

Because it is strong and light, titanium has long been used in the construction of tanks, aircraft and the space shuttle. Most titanium used in the United States, however, is converted to titanium dioxide, a white opaquing agent used in paints and papers.

"This is one of our country's greatest treasures, possibly the largest titanium deposit in the world," Gillibrand said of his mining claim.

At peak operation, the plant would produce up to 400,000 metric tons of ilmenite per year. Gillibrand said that would make a sizeable dent in the roughly 1 million tons of titanium feedstock the U.S. imports annually, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Mines.

The forest service plans to hold another public meeting in the area in late February, at which time public input will be sought for inclusion in the final version of the EIR.

|

|

Click to enlarge.

|

Mining Plan's Effects Debated.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | February 25, 1991.

Canyon Country — Water officials and a few residents warned Friday that the environmental effects of a proposed titanium ore mining operation in Soledad Canyon may have been underestimated.

The statements came at a forum held by the U.S. Forest Service to hear public input on P.W. Gillibrand Co.'s planned 700-acre mining claim, located on federal lands in the hills above Lang Station Road. The forest service is currently preparing a final Environmental Impact Statement to assess the project's effects on the area.

Newhall County Water District officials expressed concern over the need for more than 600,000 gallons of water per day to serve the project. NCWD pumps water from four nearby wells to serve its customers in the Pinetree area. Three of the wells have run dry, and water district officials questioned how the Gillibrand project might further affect the underground water table.

"NCWD is concerned that extraction of additional water from the local aquifer would impair our ability to provide domestic water for the health and safety of local consumers," said NCWD engineer Frank Steiner.

But project proponent Phil Gillibrand said the titanium mining operation will require no more water than his company now uses to mine rock and gravel. Gillibrand also said he discharges no waste water into the ground, which was another concern raised by the water district.

Gillibrand has been producing rock and gravel at his Soledad Canyon plant for 22 years. But in 1977, he discovered the area was rich in ilmenite, a glittering black sand mineral that can be broken down into titanium, a valuable metal.

He is now seeking federal approval to expand his operations into three planned mining claim areas, located about three miles from his mineral processing facility at Lang Station. His firm has a total of 735 mining claims over an area spanning 700 acres of forest land, he said.

Because it is strong and light, titanium has been used in the construction of tanks, aircraft, the space shuttle and missiles. About 90 percent of the titanium in the United States, however, is converted to titanium dioxide, a white opaquing agent used in paints and papers, Gillibrand said.

While the forest service and Gillibrand have said the mining proposal is environmentally sound, Oak Spring Canyon resident Ruth Kelley said at Friday's meeting there are still serious air and water quality concerns to be addressed, and protested the gravel company's long-term use of public lands.

Kelley questioned whether the project, coupled with the heavy car traffic on nearby Route 14, would aggravate air quality in the area. She also said trucks traveling through the hills to the claim areas on a network of planned roads would cause undue noise to nearby residents.

Kelley also disputed the claim that ores mined from the Gillibrand plant would be used in the defense and aerospace industries.

"I deeply regret losing parts of (the forest) to the mining of rock and gravel and ores for paint whiteners," she said.

Gillibrand admitted that once he begins the mining operation, most of his product will be sold to companies that will convert it to paint and related materials. Eventually, however, he expects to sell the ore to Dupont and other U.S. firms that will use it to manufacture metals, he said.

At peak operation, the plant would produce upwards of 400,000 metric tons of ilmenite per year. Gillibrand says he hopes to make a dent in the U.S. titanium market — which imports most of its titanium ore — but admits that for the first several years, his customers will likely be foreign companies.

The comments by Kelley, and of one other resident were among the first traces of opposition to a project that heretofore attracted little public interest. A similar meeting held last September reportedly attracted few interested persons. According to the draft EIS, the closest homes to the project are in the Oak Spring Canyon area, about 3,300 feet west of a proposed truck road.

Santa Clarita City Councilwoman Jo Anne Darcy was also present at the meeting, and said the City Council has given the Gillibrand project its blessing. "They've worked it out so well, 1 don't see how there could be much opposition," Darcy said.

|

Forest Service Approves Titanium Mining Proposal.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Monday, November 18, 1991.

Click to enlarge.

|

Santa Clarita — The U.S. Forest Service has approved P.W. Gillibrand Co.'s titanium ore mining proposal, but the sluggish economy may keep the firm from starting the Soledad Canyon operation as soon as it would like.

"We're not going to be moving ahead very promptly because of the economy," said Phil Gillibrand, owner of the company that has mined rock and gravel in the area for more than 22 years.

"We would like to start it now, because we feel we're in for two flat years. It's going to take a long time to get some of this stuff going," Gillibrand said. "We would like to start sometime next year, but it depends on whether we can raise the capital."

Currently, he said, that appears to be a difficult task.

The Forest Service this week released the final environmental impact report for the project and the ruling by Angeles National Forest Supervisor Michael Rogers, who determined the proposal "will not have a significant impact on the environment."

Although the project site covers 700 acres, Gillibrand said only about 100 acres will actually be mined and the mine site will not be visible to nearby residents or motorists. "Nobody can see it. The only way you can see it is to fly over."

The approval allows Gillibrand to expand into three mining claim areas on Forest Service land, about three miles from his mineral processing plant at Lang Station. In 1977, Gillibrand discovered the hills above Lang Station Road are rich in ilmenite, a glittering, black, sandy mineral that can be broken down into titanium.

Titanium is light and strong, so it is used in construction of tanks, aircraft, the space shuttle and missiles. Gillibrand says about 90 percent of the titanium mined in the United States is converted into titanium dioxide, a white opaquing agent used in paints and papers. The Soledad Canyon mine could produce 400,000 metric tons of ilmenite per year.

Gillibrand first sought the approval from the Forest Service about four years ago. "We're glad to have it done."

Charlie McDonald, environmental coordinator for the Forest Service, said concerns raised during public hearings this year were addressed by Gillibrand. For example, the Newhall County Water District was concerned that the operation would increase the amount of water used by the mining operation, but Gillibrand assured water and forest officials that the new project would not increase water use.

McDonald said an 1872 federal mining law allows Gillibrand to mine the forest property without paying the federal government. Just like in the old West, Gillibrand can stake his claim and, if no significant environmental damage is expected, remove die ilmenite from the site.

"We did not find any major significant impact," McDonald said. "That's the law of the West, if you will — it's still in effect and it's still valid."

|

About Soledad Canyon Mining.

Ever since Francisco Lopez unearthed his famous gold nuggets in Placerita Canyon in 1842, Santa Clarita Valley residents had a history of scouring the local hills for any exploitable natural resource, be it gold, oil, copper, uranium or myriad other materials. While oil flowed throughout the south side of the valley from Pico on the west to Placerita on the east, the Soledad corridor was rich in minerals that lent themselves either to surface or hard-rock mining — from shallow borates in Tick Canyon to deep gold-bearing quartz veins in Acton and even green moss agate gemstones at Ravenna in between. As noted in a report from the federal Bureau of Land Management, "Most of the historic activity in the San Gabriel Mountains has been related to mining. Placerita Canyon, the site of a gold strike in 1842, is located about 8 miles southwest of [the Lang area in Soledad Canyon]. Since that strike, gold, copper, iron, quartz and titanium have been periodically mined from Soledad Canyon." Mining sites tend to yeild more than one usable material; for instance, it is not uncommon for traces of gold and silver to occur among signifiant copper deposits.

Situated along the Santa Clara River, the area of Soledad Canyon where the Southern Pacific Railroad erected Lang Station in 1876 is particularly rich in the types of sand and gravel used in road and home construction — although other materials are extracted there, as well. Iron and titanium are mined as secondary commodities, while tertiary commodities include phosphorus and phosphates. Among the minerals present are apatite, a phosphate; ilmenite, a titanium-iron oxide; and magnetite, a highly magnetic iron oxide.

Sand and gravel may already have been mined from the site by 1921 when Sierra Highway was completed. Contemporary references indicate mining activity was under way in the 1930s, and various state mining reports record activity from at least 1948 onward. Throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, one of the major operators at Lang — roughly one-quarter mile east of the present-day 14 Freeway exit at Shadow Pines — was P.W. Gillibrand Co. The company was founded in 1957 by Philip Walton Gillibrand, an ex-construction worker from Tapo Canyon in Simi Valley. At Tapo Canyon, he began by mining and processing rock, sand and gravel to supply the construction trade and added high-quality industrial sand to the company's product line in the late 1970s. Gillibrand (pronounced JILL-a-brand) has mined not only sand and gravel in the Lang area, but also iron, titanium and phosphates.

Gillibrand wasn't alone. In the late 1960s, the family of Placerita Canyon resident Ben Curtis — veterans of the construction aggregate business since the 1930s in Spokane, Wash. — moved to Southern California to build a batch plant for a client. In time, the Curtis family acquired a 185-acre property at Lang where sand and gravel had been mined since 1955. Included was a crushing, washing and screening plant built in 1969. As of 2012, Curtis Sand & Gravel extracts 300,000 to 450,000 tons of material per year from the Santa Clara River bed at its Lang Station Aggregate Plant, where it processes the sand and gravel into Portland cement concrete aggregates.

In addition to Curtis and Gillibrand, operators in the area as of 2002 included CalMat/Vulcan, National Redimix (a concrete batch plant), Industrial Asphalt (asphalt plant), Lubrication Company of America (a former oil recycling facility) and a small topsoil supplier.

Mining activity is performed under contract with the federal government, which owns the area's subsurface minerals. In 1990, the Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management awarded two consecutive 10-year leases which, if executed, would increase production levels in Soledad Canyon by roughly a factor of 10. The twin permits allow the lessor, Transit Mixed Concrete (which was subsequently acquired by Southdown Corp., then by Cemex), to extract 78 million tons of material to produce 56 million tons of concrete aggregates over 20 years. Curtis, who owned the surface rights to the 460-acre property (i.e., the land), had bid the federal contracts but was unsuccessful and now would have to watch another company mine that parcel. Curtis stymied Transit Mixed's efforts to commence mining. In 1998 the U.S. District Court affirmed the authority of Transit Mixed and the BLM to access Curtis' property, and the U.S. Court of Appeal upheld the ruling in 2000.

The city of Santa Clarita entered the fray in 1999 when then-Mayor Jo Anne Darcy questioned the validity of Transit Mixed's contracts, as Curtis had done. The city waged a publicity campaign, filed an environmental lawsuit and pursued federal legislation to cancel the new mining contracts on grounds that the increased mining activity would harm air quality, clog roads and freeways with more gravel trucks, and threaten endangered fish and wildlife species. Along the way, in hopes of strengthening its legal standing, the city purchased the surface rights to the land from Curtis. "The size and scope of the mining project Cemex wants to locate in Soledad Canyon is far too large to be near more than 500,000 residents in the north Los Angeles County region," a city official said. Cemex chastized the city for "spending taxpayer dollars on a campaign of myths and nonfactual information." As of mid-2012, more than two decades after Transit Mixed received the go-ahead from the federal government, the increased mining hasn't happened — but neither has judicial or legislative relief. The fight continues.

About the photographer: Photojournalist Gary Thornhill chronicled the history of the Santa Clarita Valley as it unfolded in the 1970s, '80s and '90s. From car races in Saugus to fatal car wrecks in Valencia; from topless beauty contests in Canyon Country to fires and floods in the various canyons; from city formation in 1987 to the Northridge earthquake in 1994 — Thornhill's photographs were published in The Los Angeles Times, The Newhall Signal, The Santa Clarita Valley Citizen newspaper, California Highway Patrolman magazine and elsewhere. He penned the occasional breaking news story for Signal and Citizen editors Scott and Ruth Newhall under the pseudonym of Victor Valencia, and he was the Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff Station's very first volunteer — and only the second in the entire LASD. Thornhill retained the rights to the images he created; in 2012, he donated his SCV photographs to two nonprofit organizations — SCVTV and the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society — so that his work might continue to educate and inform the public.

About the photographer: Photojournalist Gary Thornhill chronicled the history of the Santa Clarita Valley as it unfolded in the 1970s, '80s and '90s. From car races in Saugus to fatal car wrecks in Valencia; from topless beauty contests in Canyon Country to fires and floods in the various canyons; from city formation in 1987 to the Northridge earthquake in 1994 — Thornhill's photographs were published in The Los Angeles Times, The Newhall Signal, The Santa Clarita Valley Citizen newspaper, California Highway Patrolman magazine and elsewhere. He penned the occasional breaking news story for Signal and Citizen editors Scott and Ruth Newhall under the pseudonym of Victor Valencia, and he was the Santa Clarita Valley Sheriff Station's very first volunteer — and only the second in the entire LASD. Thornhill retained the rights to the images he created; in 2012, he donated his SCV photographs to two nonprofit organizations — SCVTV and the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society — so that his work might continue to educate and inform the public.

GT8703: Download larger images and archival scans here.

|

|

P.W. GILLIBRAND

SCV Mining Operations

|

Titanium Mine: Photos & News Reports

Titanium Mine: EIS 1991

|

|