|

|

William S. Hart

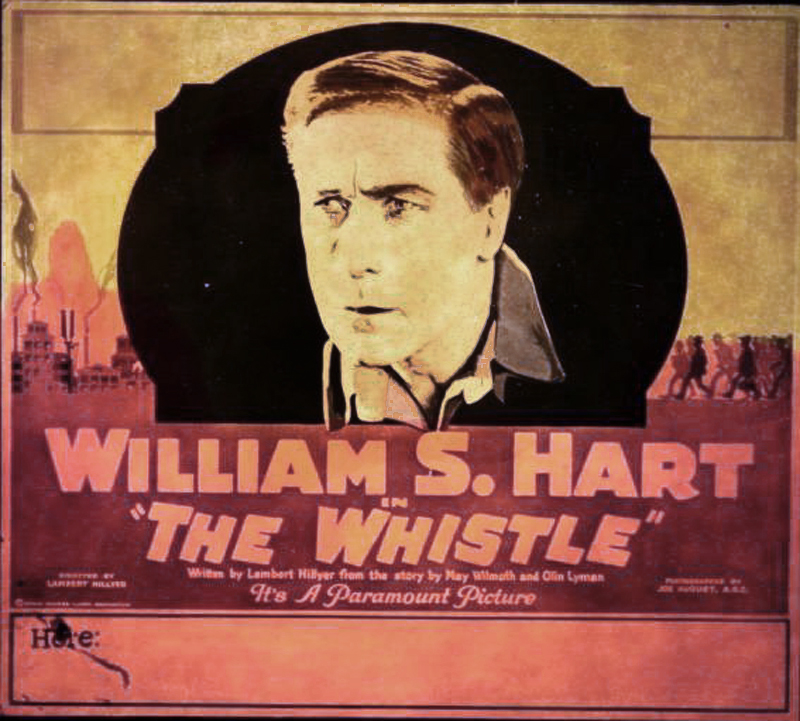

Magic lantern slide for the 1921 Lambert Hillyer film, "The Whistle," produced by its star, William S. Hart.

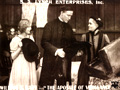

Just as his earlier stage career took him from Shakespeare to the American West, William S. Hart's film career wasn't limited to portrayals of cowboys. Labor unrest was capturing national headlines after World War I as more and more workers organized, and Hart jumped into the fray feet-first with "The Whistle" (as in a factory whistle). Hart portrays an industrial laborer in New England who avenges his son's death in a workplace accident that resulted from a greedy factory owner's refusal to implement costly safety measures. Despite critical acclaim (see below), "The Whistle" wasn't the sort of fare Hart's fans were used to, and the picture failed at the box office (Davis 2003:150). It was even banned in some states because of the controversial subject matter (Koszarski (1980:131). About "The Whistle." From Koszarski (1980:131): Produced by the William S. Hart Company; distributed by Paramount-Artcraft; New York premiere March 27, 1921; released April 23, 1921; ©February 4, 1921; six reels (5,359 feet). Directed by Lambert Hillyer; screenplay by Lambert Hillyer from a story by May Wilmoth and Olin Lyman; photographed by Joe August; art director, J.C. Hoffner; art titles by Harry Barndollar. Print sources: LC; Blackhawk; Em Gee. CAST: William S. Hart (Robert Evans); Myrtle Stedman (Mrs. Chapple); Frank Brownlee (Harry Chapple); George Stone (George Chapple); Will Jim Hatton (Danny Evans); Richard Headrick (Baby Chapple); Robert Kortman (Scardon). SYNOPSIS: "The Whistle" is a story of capital and labor. Robert Evans and Danny, father and son, are workers in the shop of Henry Chapple, a hard-headed business man. Evans as foreman of the shop urges Chapple to make repairs necessary to avoid accidents. Chapple talks of contracts to be filled and refuses. That day Danny is caught in a defective belt and killed. Evans is walking by a river, in an emotional frenzy over his son's death, when Chapple's automobile plunges into the water. He rescues Chapple's infant son, who was in the car with the chauffeur and, bitter at having lost his boy, kidnaps the infant, leading the Chapples to believe their child dead. (He and the boy wander far from New England, seeking work in the West.) Chapple befriends Evans, and when the working man sees that Mrs. Chapple's life is dependent upon having the boy he claims as his adopted son, and when Chapple reforms, he confesses his deed and returns the child. (Moving Picture World, April 9, 1921.) REVIEWS: This should stand out as one of the finest contributions William S. Hart has given the screen. The story is rather tragic, that of a plain, middle-aged millhand who seeks to avenge the death of his son, and the love theme is entirely one of parent love. Such a plot would not make for success in a photoplay, were it not for careful direction, and with the dignity and repression with which Mr. Hart enacts his role: a drab picture, painted with brilliant touch. (Photoplay, July 1921.) From start to finish the picture grips its audience ... Hart dominates whenever a display of emotion is called for, and that is often. The story is sensible in that it does not attempt to solve the age-old problem of capital and labor. It begins with a series of accidents that hit the nerves rather hard, and turns into a man's struggle with his conscience. The accidents are entirely essential to the development of the plot, but it was unnecessary to hold the close-up so long on the mangled body of the dying boy. ... The picture will please all Hart fans (though the star does not wear chaps) and ninety-nine out of every hundred others who appreciate good drama and excellent emotional acting. (Sumner Smith, Moving Picture World, April 9, 1921.) |

WATCH FULL MOVIES

Biography

(Mitchell 1955)

Narrated Biopic 1960

Biography (Conlon/ McCallum 1960)

Biography (Child, NHMLA 1987)

Essay: The Good Bad Man (Griffith & Mayer 1957)

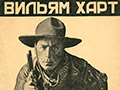

Film Bio, Russia 1926

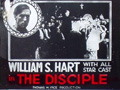

The Disciple 1915/1923

The Captive God 1916 x2

The Aryan 1916 x2

The Primal Lure 1916

The Apostle of Vengeance (Mult.)

Return of Draw Egan 1916 x2

Truthful Tulliver 1917

The Gun Fighter 1917 (mult.)

Wolf Lowry 1917

The Narrow Trail 1917 (mult.)

Wolves of the Rail 1918

Riddle Gawne 1918 (mult.)

"A Bullet for Berlin" 1918 (4th Series)

The Border Wireless 1918 (Mult.)

Branding Broadway 1918 x2

Breed of Men 2-2-1919 Rivoli Premiere

The Poppy Girl's Husband 3-23-1919 Rivoli Premiere

The Money Corral 4-20-1919 Rialto Premiere

Square Deal Sanderson 1919

Wagon Tracks 1919 x3

Sand 1920 Lantern Slide Image

The Toll Gate 1920 (Mult.)

The Cradle of Courage 1920

The Testing Block 1920:

Slides, Lobby Cards, Photos (Mult.)

O'Malley/Mounted 1921 (Mult.)

The Whistle 1921 (Mult.)

White Oak 1921 (Mult.)

Travelin' On 1921/22 (Mult.)

Three Word Brand 1921

Wild Bill Hickok 1923 x2

Singer Jim McKee 1924 (Mult.)

"Tumbleweeds" 1925/1939

Hart Speaks: Fox Newsreel Outtakes 1930

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.