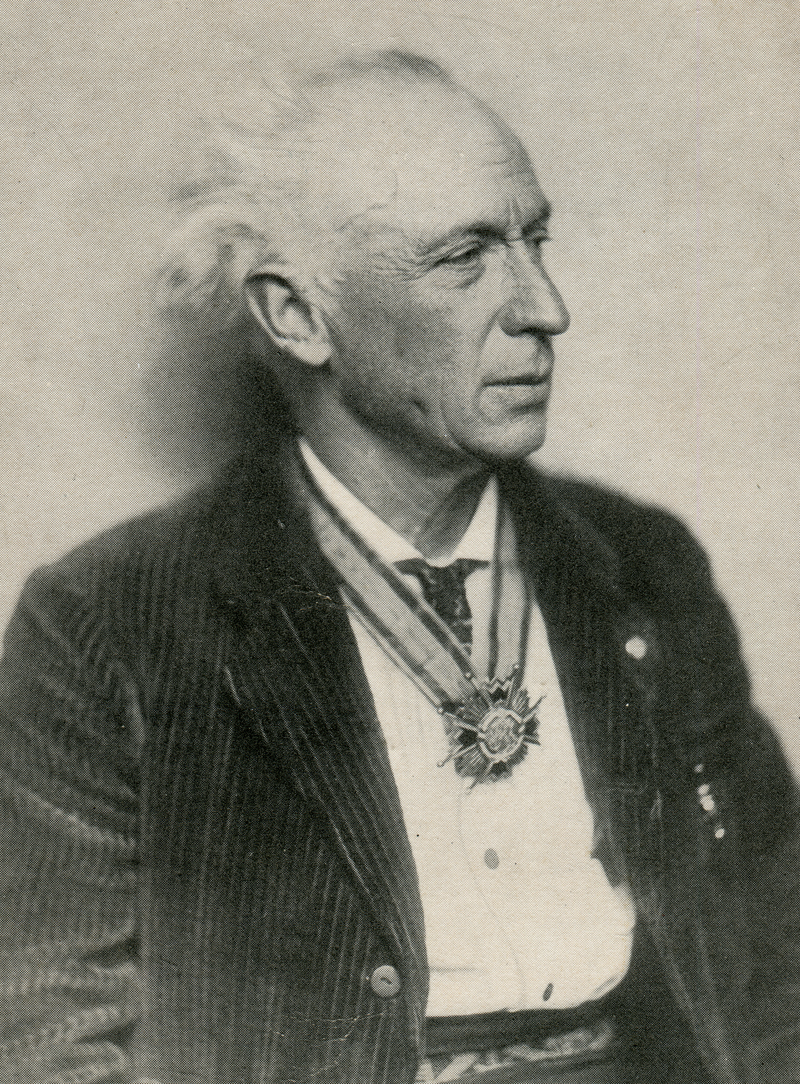

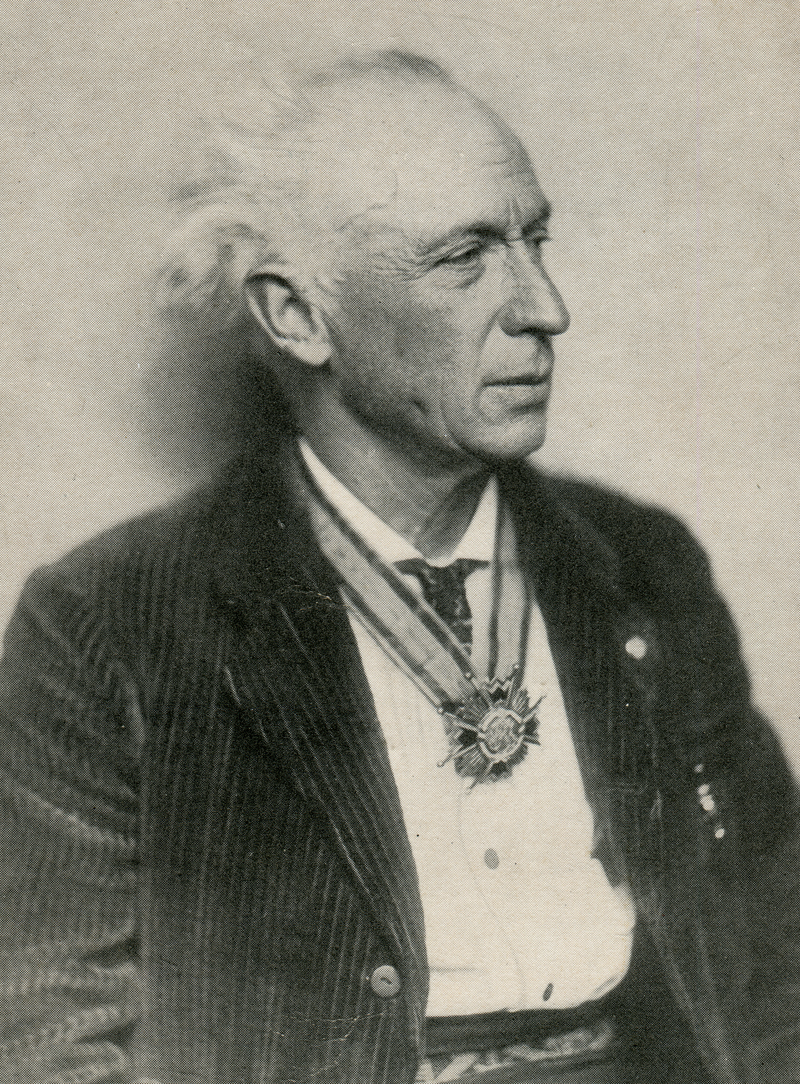

Mission San Fernando, sometime before it was restored in the 1940s.

This was its "good side" at the time; the other walls were crumbled.

Mexico's Secularization Act of 1833 completely dismantled what was left of the mission system after 12 years of independence from Spain. Lands previously owned by the Spanish crown and controlled by mission friars — most of the land in Alta and Baja California — were assigned to commissioners who were supposed to apportion them into town plots, communal pastures, and individual sections for local Indian families.

Many Indian families who were assigned such tracts of land, which weren't particularly well delineated, were relieved of them through swindles not unlike the proverbial sale of Manhattan Island for the equivalent of $24.

Meanwhile, the mission priests were left only with the church buildings, their own living quarters and a kitchen plot, while the commissioners sold off the mission property (livestock, orchards, etc.), frequently to the enrichment of friends and political allies. A few of the mission buildings themselves, including San Fernando, fell into private hands.

While only about 30 ranchos had been set aside for private use under Spanish rule, now the number exploded to more than 800. Lands under the prior jurisdiction of the Mission San Fernando became Mexican land grants in 1839 when Mexico's governor for Alta California, Juan B. Alvarado, awarded the 48,000-acre Rancho San Francisco in the Santa Clarita Valley to Army Lt. Antonio del Valle; and again in 1846 when Gov. Pio Pico granted the Rancho San Fernando to Eulogio de Celis.

After American conquest in 1848, the U.S. government upheld many of the Mexican land grants, including the ranchos San Francisco and San Fernando, but many Mexicans, Indians and foreign immigrants were dispossessed of their real estate when they couldn't produce documentation of clear title or, in the case of many Indian populations, were not informed of the requirement to do so by Act of Congress in 1851 (not that they necessarily could, had they been told).

Lands where no clear title could be established, including the prehistoric range of Indians between the ranchos San Fernando and San Francisco and in upper San Francisquito Canyon, became U.S. government property and were assigned in 160-acre chunks to homesteaders, who had to establish residency and start farming or ranching within five years. Under the first-come, first-served U.S. patent system, homesteads typically went to the first person to file a patent, regardless of whether the land had been, or still was, occupied by indigenous peoples. Thence came the infamous Indian evictions from Temecula, Warner's Ranch in San Diego County, and elsewhere.

Along the way, with neither Mexican nor later American political support for the mission system and no more Indian subjugates to maintain the mission properties, the old mission buildings fell into disrepair.

In 1845, Pio Pico declared the Mission San Fernando for sale and leased it to his brother, Mexican Army Gen. Andres Pico. After the war, in 1853, Andres obtained a one-half interest in De Celis' Rancho San Fernando, and it was divided in half. (The mission, where Andres continued to live, was physically located on De Celis' half.)

From the no-man's-land between the ranchos San Francisco and San Fernando, in the canyon that now bears his name, Andres extracted asphaltum - just as Indians had done centuries earlier - and used it to patch the roof of his crumbling mission home.

In 1862 Andres was in debt (which might explain why he couldn't complete the road he was hired by the county to cut through the pass between the ranchos; Ned Beale had to finish it). Andres sold his half of the Rancho San Fernando to his brother Pio, who subsequently sold it to Isaac Lankershim.

In 1874, the heirs of De Celis sold his half to state Sen. Charles Maclay and his partners, George and Benjamin Porter.

Although the Mission San Fernando reverted to the Catholic Church when Andres Pico sold out, the buildings weren't restored at that time. Part of the property — a section that's beneath the current Van Norman Reservoir — became the site of Lopez Station, an 1850s-60s stagecoach stop; in 1896, the area surrounding the mission became a hog farm (read: old-fashioned waste disposal method). At one point, the mission itself was used as a warehouse for the Porter Land and Water Co.

Interest in preserving Alta California's 21 missions as historical relics slowly started to gain traction in the 1890s and early 1900s thanks in large part to Los Angeles journalist and Indian rights activist Charles Fletcher Lummis, who used his successive "Land of Sunshine" and "Out West" magazines to advance his causes. Lummis took the helm of the Landmarks Club of Southern California, which purpose was to prevent the adobe-walled mission buildings from returning to the earth from whence they sprang.

Interest in preserving Alta California's 21 missions as historical relics slowly started to gain traction in the 1890s and early 1900s thanks in large part to Los Angeles journalist and Indian rights activist Charles Fletcher Lummis, who used his successive "Land of Sunshine" and "Out West" magazines to advance his causes. Lummis took the helm of the Landmarks Club of Southern California, which purpose was to prevent the adobe-walled mission buildings from returning to the earth from whence they sprang.

Lummis, who founded the Southwest Museum of the American Indian in 1907 (now part of the Autry National Center) had a well-heeled ally in Phoebe Apperson Hearst (1842-1919), wife of U.S. Sen. George Hearst and mother of San Francisco newspaper magnate William Randoph Hearst. Keenly interested in archeology, Phoebe founded the Museum of Anthropology at U.C. Berkeley in 1901 and funded Lummis' endeavors with the Landmarks Club.

Phoebe's philanthropic tendencies passed down to future generations. Mission San Fernando became an active church again in 1923, but it took funding from the Hearst Foundation in the 1940s, during her son's lifetime, to restore the buildings to their former glory.

Today they're in even better shape, structurally. The mission was heavily damaged in the Sylmar-San Fernando earthquake of Feb. 9, 1971, and was completely rebuilt. It reopened in 1974 and continues to serve as a museum and chapel, a level below a parish church.

— Leon Worden 2013