|

|

|

Webmaster's note.

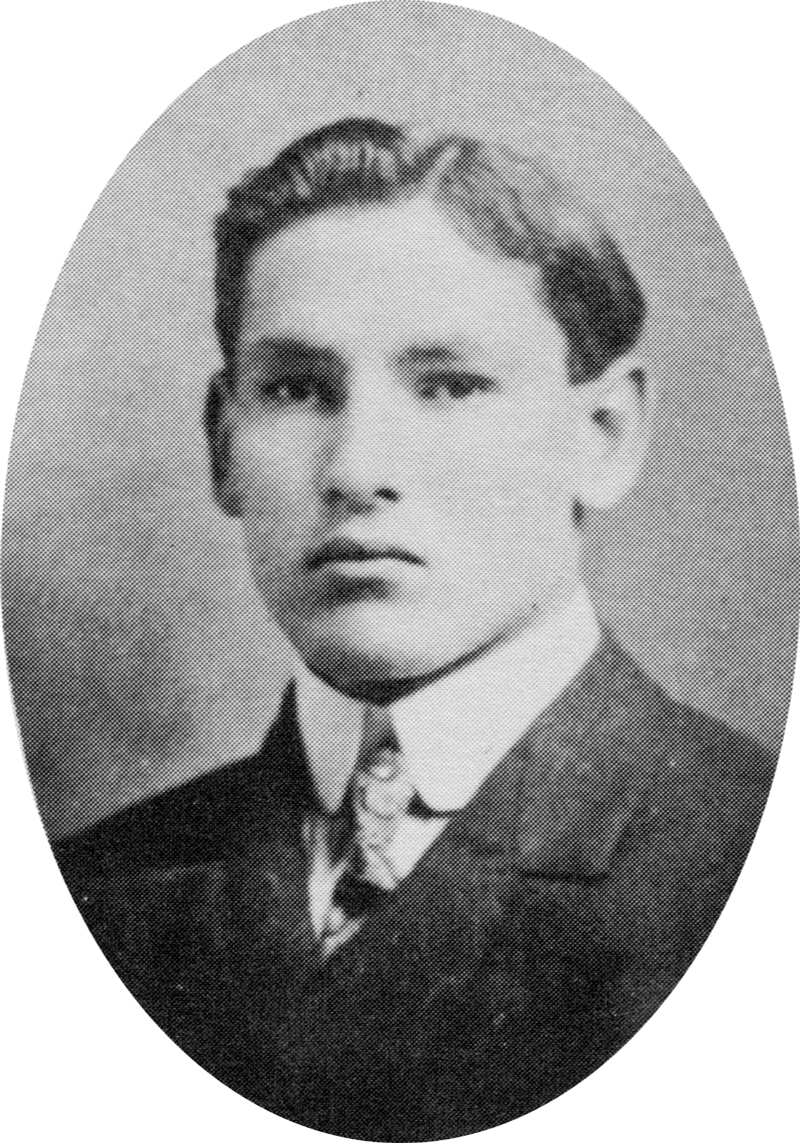

Alberta W. Platz Bell, 1915-2005, was raised on a ranch on Escondido Canyon Road (then outside of Ravenna, today considered Agua Dulce). Except for a stretch in the 1930s when she lived in Glendale, Alberta lived in the Acton-Ravenna area her whole life. She involved herself in social organizations and activities, even serving as Acton's county librarian from 1947 to 1949, and helped shape Acton into the community it is today. As much as R.E. Nickel was the "Father of Acton" in the 19th Century, Alberta Bell mothered it in the 20th. Her parents, Eugene John "Ed" Platz (May 19, 1887 - Oct. 26, 1950) and the former Nettie Gipp (April 7, 1895 - May 4, 1967), lived on the Heffner (ex-Gross) Ranch on Escondido — Nettie's family as leaseholders, Ed as a hired hand. They eloped in San Francisco in 1912. The young couple moved to Pasadena and returned to Agua Dulce in 1916 to take over the operations of the Heffner Ranch, where they remained until 1933 or 1934 when they bought the "Old Rayburn Place" in Acton. In addition to ranching, Ed Platz worked as a Southern Pacific Railroad pumper until his retirement in 1949 (see Meryl Adams 1988:204). On Dec. 2, 1988, Alberta dictated her childhood and young-adult memories. We don't know if it was done in one sitting, but we know the 1988 date because her monologue is interrupted with the announced liftoff of a space shuttle. As it appears here, information in (parentheses) is in the original transcription, while information in [brackets] has been added by the editor. Otherwise, it's unmodified except for the slightest of style corrections. For instance, whenever Alberta recited a list ("x, y and z"), she tended to omit the "and"; it's been added here for readability. Also, the original monologue/manuscript is text-only. Images, section headers and modified pull-quotes have been added for this version. It is complete so far as we know; toward the end, Alberta indicates her intent to discuss her life with James C. Bell (1917-1988), from whom she was widowed, but if she did so, we haven't seen it. Alberta and Jim Bell are buried together in the Acton Community Cemetery. Alberta's parents rest at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale.

"To All of the Family Whom This Concerns..." Once upon a time there were two sets of grandmothers, Emma Mae from Alsace-Lorraine and Mary Von Kannler from Germany; and two grandfathers, Ehrhardt Gipp from Prague and Henry Xavier Francis Joseph Platz, who was reared in a monastery by a monk-type uncle named Platz, somewhere in Germany (see Sandra Platz Yager for details or Al Klaner for location). Mary and Ehrhardt met in New York, married and went to Chicago for a honeymoon, got the "Westward ho" itch and landed in Los Angeles, bought property near First and Main streets which he later traded "even up" for property in the Acton area near Agua Dulce Road. Mary, coming from a titled, wealthy family, never saw her family again and led a hectic, submissive life. After bearing six daughters (Nettie, my mother) and one son, she died at age 45. (See Hall of Records for details.) Ehrhardt died at age 56 from indulging in too much fine food — which he withheld from his children, causing them to be malnourished near starvation at times.

Emma and Henry married in ? Germany, lived in New Jersey and reared 13 children. My dad, Eugene, was one of the five boys. At age 6, the boys were put to work in the silk mills, working 10 to 12 hours a day to contribute to the family support. Eugene, my Pa, had a sixth-grade education, which is the equivalent to the present twelfth grade. More about him later. Emma was a cook trained in France, and worked in wealthy homes. Several of the daughters learned the French cooking tricks. When I was 5 years old, Henry and Emma traveled west to see "Euch" via rail, seven nights and days of sitting in a Pullman coach. All I can recall is the boisterous after-meal conversations; the main subject was the Bolsheviks. Grandma Emma, then in her 70s, was a hiker. There are snapshots of her sitting on the rocks above Ravenna. She related her weekly treks from Patterson, N.J., to New York, a 10-mile walk each way.

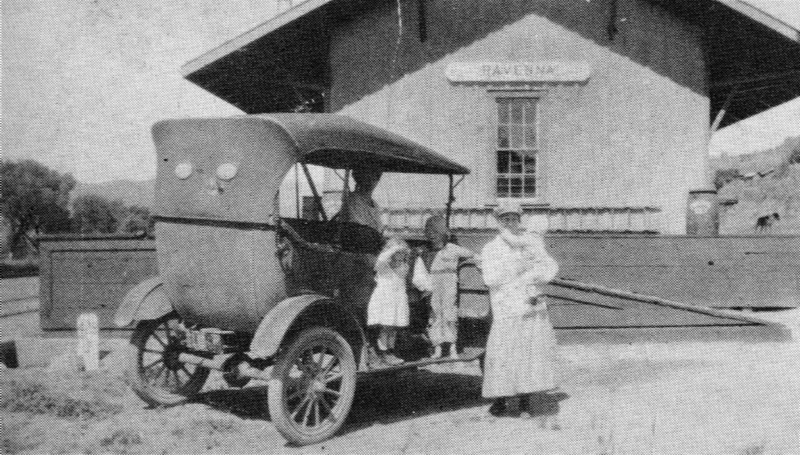

Coincidentally, both grandpas were shoe makers, New York being the central area for manufacturing shows at that time. E. Gipp made the classy type for wealthy people; also special dancing slippers. H. Platz made the sturdy type; it helped him to shod his own family. He taught Dad how to resole shoes. I can still see the shoe lasts piled in the closet behind the fireplace in the old Heffner house. When it became time to fix a shoe, out came the shoe-fixing equipment, mit der clankin' and der clinkin'. Dad had me hand him the shoe nails one at a time; otherwise he would take a mouthful of them and spit out one at a time as he needed it. He had large pieces of leather from which he shaped a sole, according to size. He used the standard "shoe tapping" hammer, a cute thing, I thought. That was only one of Dad's many talents. My mother, Nettie Gipp, left home at age 14 to live in and work for a family that lived behind the brick school on Cory Street. Later her brother, Emile, got her a job with a family who ran the Borax mine in Tick Canyon, Emile being a teamster who hauled ore from the mine to the Lang railroad station. Mom became a terrific cook. She followed her brother to cook for him when he switched jobs and farmed on the Heffner Ranch. Then it all began! A Growing Family Uncle Emile advertised for a helper on the farm. Guess who turned up? My dad from New "Joisy," who had spent his younger years working on all sorts of farms, working his way West. As he drove — riding with Uncle Emile, who met him at Ravenna a the train depot — up the heavily tree-shaded lane, a lovely 16-year-old, Nettie Gipp, opened the gate for them and he stated, "It was love at first sight." It really was and became a long-lasting kind of love that lasted forever. They exuded love for each other and us kids. They even demonstrated love for their neighbors in many ways.

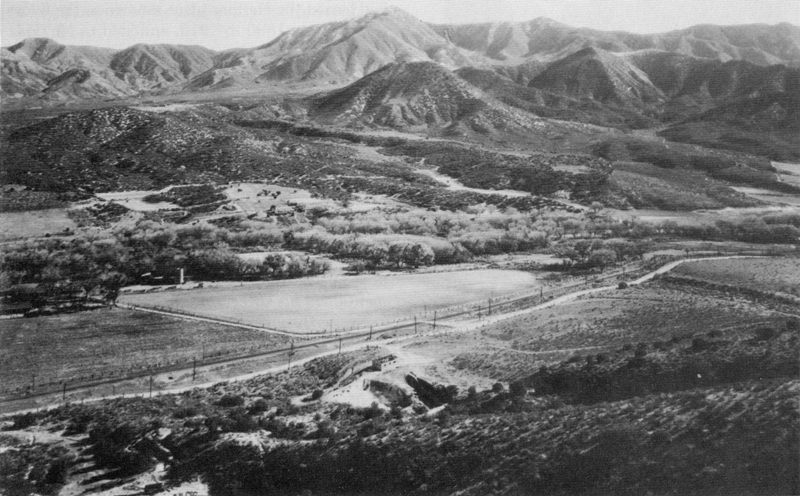

May 30, 1912, Eugene and Nettie married and honeymooned to Eureka, California. He went to work in a lumber camp near Dyerville (no longer there). They tried their hands at a small cafe, catering to the lumber workers, with Dad doing all the cooking and Mom being the waitress. Uncle Albert Platz, Dad's younger brother, coerced them to move to Pasadena, where he got Dad a job on the Red Car line that went to Los Angeles several times daily. Al was the motorman and Dad was the conductor. The lived on Villa Street, Pasadena, and became sorry that they left Eureka. Uncle Emile gave up the Heffner Ranch to farm a ranch inherited from his father and became a bee and honey raiser. So Dad, loving farming, took over the Heffner Ranch. In time, it became a very successful dairy farm. He raised all of his own animal feed by developing four alfalfa fields. He used horses to draw all of the hay making equipment. He had a special horse barn for never less than three teams. He built three dams on the "crick" (Santa Clara River) which ran through the farm, to irrigate the alfalfa fields. He used huge gasoline engines at each dam to pump the water to each field. All of this work required many hands, so he had several hired men who slept in the bunk house and ate with us at meal time. Most hirees were imported from Germany, Switzerland, Austria, etc., all knowledgeable dairymen. We kids were fascinated by their stories from their homelands and kept us spellbound on long winter evenings, sitting around our fireplace in our parlor. With all of the long work hours, Dad, being a fun person, always saw to it that we — including the hired help — had recreational time. I should insert that the family grew. Eugenia, No. 1 child, died at 2 years minus 4 days, July 17, 1915. I was 6 months old at the time, but I recall Mom pushing me in a carriage — a large-wheeled wicker thing — on long walks to try to relieve her devastation of losing Eugenia. Dad had taken the train to Los Angeles on business, a two-day trip at the time. When he alit from the train in Ravenna, the depot agent informed him that his baby had died, thinking it was me. The doctors attributed her death to pneumonia. I am No. 2 child, who was a trial to my parents in my early years because of my "redheaded" temper. At age 2 I could not be forced to pick up a doll I had thrown to the ground. Years later, I was reminded of "I-Won't-Pick-Dolly-Up!" Dad took my hand and laid it on the doll, but I wouldn't close my hand to grasp it. He gave me a few soft pats and gave up.

Virginia Alvina, whom we called "Sis" her entire life, was No. 3. She was a mild-tempered child, a beauty with long auburn curls and a peaches-and-cream complexion. A Pasadena dairyman named Delbridge offered my folks $1 million for her, but Dad told him that she was worth much more than that to him. She grew up to be calm and talented in music, art, needlework of all kinds, mother and homemaker; generous to the core, always giving and finding it hard to receive from others. We were fun companions up through our school years. She died of heart problems at age 62. And then there came Edward Hanford, better known as Buddy, No. 4 child. The first and only boy. I thought Dad would explode with joy. Buddy became an active, teasing-us-girls, cute, bug-eyed blonde with a Dutch bob until school years. He was the champion thumb sucker, after me. He loved his horses. At age 14, he contracted lobar polio — the first victim to have survived it. After returning home from the hospital, his first wish was to go to the horse barn to smell its aroma. He outgrew the paralyzed tongue which caused a speech defect for a few years. More about Buddy later. Then came Nettie Evelyn, No. 5, nicknamed Nonnie. She was the prettiest, redheaded, pink-cheeked baby. At the time I was 9 years old, so it was my job to change her diapers. Once after a change, she squirmed an unusual amount, and in redoing her diaper, I saw two safey pin holes. I had attached her to the diaper. Each afternoon I had to get her to take her nap, so I put her in that huge baby buggy and rolled her back and forth, at times with so much vigor that the whole house resounded because of wooden floors. Every evening, pre-bedtime, Mom sat herself beside the huge wood stove with one foot up on the lower protruding ledge to support "Baby," as she was called then, to give her a nightly massage with olive oil on her entire body. It made her "sleep better." Nonnie was also a thumb sucker up 'til school years, as [was] I and Buddy. Mom sprinkled every nasty tasting thing she could find to dip our thumbs in to stop us. I think cayenne pepper did it for me. Nonnie developed warts on her thumbs; one time I counted 59. At age 4 she composed cute pieces on the piano and being a Capricorn, developed perfect pitch and still has it. She, like Sis, is talented in various types of needlework; played organ, piano, accordion, ukulele and whatever else she is so inclined. At 18 she became a railroad telegraph operator, married, became a mother and Acton's famous bus driver and bus driver instructor. Due to a tragic auto accident, her Hal Chamberlain was killed, causing Nonnie to become a young widow. Hal was no slouch. He was a character who was a man of all trades. There was nothing he couldn't fix or at least try. He was loaded with quotes from his background, all pertinent and witty. He was a railroad switchman and worked his way to the top in the Masonic lodge. There was a time that I don't know what I and my family would have done without his help. His son Bob became a helicopter pilot and was shot down in Vietnam, leaving a wife and a daughter. Hal and Nonnie's daughter, Doris, became a nurse, wife, mother of Anne Marie and Charlotte Annette, a school bus driver. She's smart and is a nose-to-the-grindstone person who, after her second marriage, happily has learned to have some fun. One trip across country, we landed in Las Cruces for the night and tried to locate Nancy (Bob's family), but no luck. My most prominent memory of that stop was the raw chicken Jim was served in their best restaurant. With much apology, we didn't pay for our meals. No. 6 came Marion Jean, better known as Tincy, a sweet, brown-eyed blonde cutie. The apple of the family's eye. In my off-school hours, I was in charge of her. I was careful not to attack her to her diaper. We went through the same la-la procedure to put her to sleep and had the same olive oil massage, breast-fed until she was 2 years old. She was a fretful child and demanded a lot of attention. Being the last child, it was natural to become a little spoiled. She became semi-interested in music, tinkered at the piano and played violin in the high school orchestra. One memory of her was that she cried and cried; she was heartbroken when I married W.W. Roth. I think she thought she'd never see me again. I was her second mama, and I should have taken a cue from her reaction. The only good thing about my marriage was the four wonderful children we produced: Carole Hope, David Phillip, Katherine Janet and Leslie Robert. Tincy married Kit Carson and produced four children: Kathleen Jean, Kit Eugene, Charles Patrick and Steven Michael — who all married and have their own families. I sure love those kids. They all went through such trauma, as did we all when Tincy died so young at 31 of tetanus. What a needless loss. Gifts from Dad Back to Buddy. He was a bundle of nervous energy. He walked in his sleep, and one night he slept on the living room couch. Reason? I forgot. A kerosene lamp on the mantlepiece burned low, so from my bedroom I could see him. His jabber woke me, and I saw him standing on the couch in a diving position. He jumped off head first with hands together, as if diving, and hit the floor upside down, but on his descent his head clipped the corner of the square piano bench, cutting a gash above his eye and leaving a bloody cut that needed a doctor. I gave a whoop that awoke Mom and Dad. When Mom first saw him, out of her sound sleep, she fainted. Now we had two victims. She soon came out of it but was too weak to attend to Buddy. So Dad and I were chosen to drive him to the nearest doctor in Lancaster; in that time his name was Doctor Savage. I held a cold pack over his eye, and on the way there he fell asleep in my arms, but I didn't know why he did. We rode in the open milk truck — cold, windy — and the truck did its usual rattling, sputtering and clanking. The road at the time was narrow, rough, and full of ruts and oiled surface spots. After those 24 miles of misery getting there, it was close to midnight; we awoke the doctor and he let us in. The office was a tiny front room of his house, and all he did was apply a butterfly bandage. Poor Dad; he had to get up to do the milking at 3 a.m. to have milk ready to load on the 4 a.m. train at the Ravenna Depot. Buddy became the recipient of many fun toys. Every time Dad went anywhere on busniess, he brought some gifty thing to someone. He always surprised us. He bought Buddy a huge bear on rollers (steel reinforced), and he could ride it around the house. He bought him a live pet goat and cart with harness, etc. He learned to be pulled by Tsi-Tsi (the goat's name) all over the farm — all except the sandy ex-riverbed areas. He got stuck in the sand once.

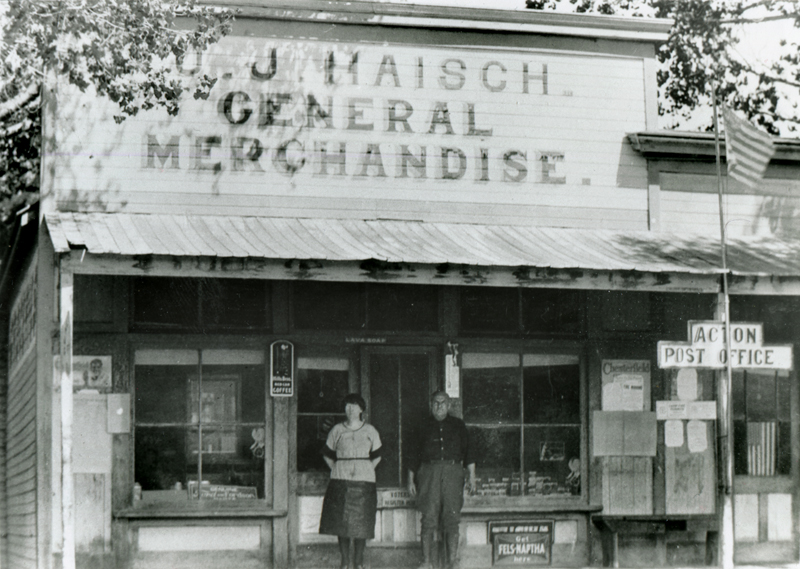

Dad surprised us all with an electric train which he hoped would stay hidden until Christmas. It ran off a huge storage battery. Dad sneaked all of this train stuff upstairs and set it up, but the little train on its track sent a suspicious sound down the stairway. Buddy's eyes popped out and he couldn't be held back. Dad bought him a mini-steam engine that ran on alcohol and gave out steam and whistled. One biggie was a full set of small carpenter tools. We heard lots of hammering, mostly on "no-no" areas. Then came the climax: He took the saw and sawed his mobile bear's head off. Sawdust spewed everywhere. Buddy loved his horse, Smoky. He learned to ride bareback and imitate Indians using bow and arrow. One day he rode Smoky to school (which we were allowed to do then). Dad and I happened to be in Acton, sitting on Captain Haisch's General Merchandise store's porch. They were chewing the fat — Dad was an interesting conversationalist — when Captain Haisch spotted movement at the railroad crossing. Riding through town to school was Bud on Smoky, followed by a foal, Tsi-Tsi the goat, Zip the German shepherd — and dragging up the rear was aging Carlo, Dad's traveling-companion mogrel dog, whenever another person wasn't available. It was a comical entourage. Bud went to school, and Dad and I herded the rest of the animals back home. I missed the high school bus that day. If only I had a camera to shoot that scene. It was very comical. Dad always brought us nice surprises from his business trips. One time he brought Sis and me gold birthstone rings. Sis was turquoise for December 23rd, which she later dropped from the favorite apple tree that we liked to climb. I lost mine between the cracks of the wooden front porch, and lost it for good. I later saw an identical ring on a girl in my class at Frank Wiggins Trade School, years later. Dad bought Mom nice dresses. I particularly remember her favorite. It was a sheer crepe in Old Rose, trimmed with much ecru lace. The skirt had millions of tiny pleats around it. She loved it. It cost a fortune to have it cleaned, but she wore it to the local social affairs for years. She even wore it to a picnic down at the river crossing. Another gift to Sis and me were gold bracelets engraved with flowers. Sis put on hers easily, but I couldn't manage the clasp and after a struggle, I threw it, and it landed under our four-legged bathtub across the hall. What a brat I was. Musically Inclined The ultimate surprise gift was loaded on a truck from the Ravenna railroad depot, ant it took several hired men to lift it into the house. A piano! However did the folks suspect that we would take to it like ducks to water? We were immediately signed up for formal lessons. I was 9 years old at that time; Sis was seven. Our first teachers gave us a bad time, expecting us to read music and find the proper keys right off. Mrs. Cozzine, my first music teacher, nursed her fourth baby as she tried to "deconstruct" me. We sswitched to Mrs. Satterwhite for lessons. She was a "pip": short, fat, no patience, and she cranked her neck like a turkey gobbler and whacked our hands when we hit a wrong note. It wasn't until [the hiring of] Ruth Fryer, a high school student friend and neighbor seven miles removed, that our lessons took hold. She gave us the best basics that became the foundation for lives revolving around music. Mom drove us down Soledad Canyon to the Fryer home every Saturday afternoon. After lessons, we were treated to Caroline's (Ruth's older sister) home-made goodies. She baked while we had lessons. I particularly remember "Sea Foam Bells" — a maple-flavored glob of air, but good. I often wondered how the folks put up with the constant piano practicing? Sis and I fought to practice. In two years, we advanced to the eighth grade in music, according to Etude magazine, and instruction music magazine. We learned solos and were commanded to play at every local entertainment. Our duets became a "must." At age 12, I was lucky enough to acquire a violin via a hired man. My first violin was recalled to New Jersey where Bertha Beckert found out it was a valuable "stainer." Lessons on it were taught by a Mr. Ahlers, who lived in Peru and was known as the "traveling preacher." He had many students scattered all over. He seemed to arrange his schedule so that when my lesson was late Saturday afternoon, he stayed over and became addicted to Mom's cooking. If there was any local entertainment that Saturday, we were part of it. After a second lesson we played a violin duet, "Juanita." This was an open-air affair and we stood on the porch of the old '49er Saloon. Lighting was furnished with many gasoline lanterns hanging about. This being a heavily wooded area surrounded by many old, huge cottonwood trees. The lanterns were attached to them in some way. Dad acquired a second violin by getting it out of hock via another hired man. Bud was then given violin lessons. They didn't take. After one year of lessons, Buddy couldn't do any more than draw the bow across the strings. I would take him out behind the barn to coach him, or we'd sit outside in the carcass of an old, defunct Ford — anywhere out of earshot from Mom. Our struggle was in vain. Bud's mind was elsewhere. One morning I accidentally went into the bathroom only to see our violin teacher roughing his cheeks, which shocked me. He needed to do anything he could to compensate for his buck teeth. Later, I played in the high school orchestra, Los Angeles Junior Symphony, Lancaster "Little Symphony," and other orchestras in Los Angeles. At that time, I was living with Beckerts to attend school, and other orchestras became available. Charlie and I were addicts to playing in any of them. That's another story. We must have come by music naturally. Dad loved it and was always making music. He played harmonica, plunked Bertha Gipp's Gibson mandolin, whanged on a Jew's harp, picked out tunes on my fiddle, carved flutes and whistles out of willows and was continually signing (he must have known every popular song of that era) while milking the cows, yodeling on and on. He also had a vast repertoire of poems, nursery rhymes and riddles. While he was milking he was entertaining us, but he'd be very slick about inserting an arithmetic problem or a spelling game or a "What's the capitol of...?" game. We didn't realize he was touching us and causing us to think. We thought it was great fun. I can't count the recordings we had. Each trip to Los Angeles, mostly by train, we'd head for the California Music Co. We'd sit in one of several soundproof booths and listen and choose a new record. Dad loved John McCormack, Alma Gluck, Enrico Caruso, Uncle Josh and the John Phillip Sousa band. He bought the first floor-model phonograph in Acton, which drew in neighbors. Then after hearing his first radio, a "cat's whisker," at the family's house when and where Nonnie was born, he was the first to buy a superhetrodyne radio. It was powered by running a cord through or living room window and clamping it to the Ford battery that he drove next to the house. This gave us entertainment evenings only, after the Ford finished for the day. Before that, though, all of Acton gathered each evening at Haisch's store to hear Amos and Andy. We'd sit on the porch summers, and crowd into his parlor in cooler weather. Life on the ranch

I became my dad's "boy helper" in the dairying department. When all the hired help was busy making hay, I was elected to set up the sterilized milk equipment to prepare for the evening milking. I had to switch 10-gallon milk cans as each got full, cap it properly, tag it (special tags to Los Angeles Creamery with Platz stamped on them), and shove it close to the trough where 300-pound cakes of ice would keep it cold until the next morning's shipment. After the milking was finished, I had to wind up everything: Tear down the equipment, wash it, put it in the sterilizer (a huge, square vat perched on bricks so that a wood fire could be stoked under it). It got the equipment — with a certain amount of added water — boiling hot. Dad always got an A-plus report from the creamery for cream content and free of bacteria. After the milk house was ready for the next milking, I cleaned the barn. I had to hand-shovel the gutter stuff into a wheelbarrow and wheel it out of the south door to dump it down a hill where a pile accumulated. There were countless loads. After that, I took a stiff push broom and water hose and scrubbed the barn's cement floor. I'd always have wet feet; sometimes they got almost frozen. I wonder if that's where I contracted "cold feet syndrome"? This process was repeated again at 2 a.m. by the hired help. I only worked after school. After the morning milking, it was all loaded in the Ford pickup — Dad custom-made the truck bed for milk can carrying — and driven to the Ravenna railroad station for shipment to the Los Angeles Creamery. If Dad arrived late, the agent held the train until Dad arrived and loaded it. Two times he missed the train entirely, so he'd make a beeline to Saugus railroad station, hoping to get there first. One time Bud and I wanted to go with him, so we headed up to Mint Canyon Road to wind up our way there. It was a long, bumpy, curving road then. As we arrived at the first intersection — now Crown Valley and Sierra Highway — we had a collision with a speeding carload of Los Angeles city officials. Their car went out of control, turned over several times and raised so much dust, we couldn't see "the happening." When it settled, out crawled four elegantly clad men, not hurt but dusty, and we saw one of them toss a whiskey bottle into the weeds. All they did to us was clip off our front right wheel, and we slowly sank. We had this nice front-row seat to view this earthshaking event. At that time, the juniper trees were close in up to the road, so Dad couldn't get a good view of the oncoming traffic. Somewhere, Mom got word that we had a wreck, and after a short while, I saw her walking up the road (Crown Valley). She came from four miles away; I never found out how she got there so fast. Needless to say, she was greatly relieved to learn that only the truck got hurt. Dad, being a jack of all trades, fixed it after being towed home. He had a fully rigged blacksmith shop and could fix anything in wood, leather or metal. He was the neighborhood fixer upper. Neighbors came from far and near to have Ed Platz fix whatever needed fixing.. He made and mended harnesses, shod his own horses (making his own horse shoes; I turned the handle), kept all of his haying equipment in repair, and invented several things. Among them was an automatic toilet flusher, a gas-saving addition to a carburetor, a garden tool (I still have the applied-for patent papers on it); created necessary gadgets to assist him in assorted projects like retrieving a dropped pump from down a well, etc. Another talent of his was learning to be his own veterinarian, doctoring horses, cows, dog, etc. A neighbor's cow had trouble birthing her calf, so he was summoned. Inserting his hand and arm into the cow, he turned the calf around to its correct position, and all was well. One of our horses, while chasing around the corral, ripped off a foot-and-a-half-long splinter from the plank fence. The splinter went into its chest, barely missing the heart. Dad tethered the horse, removed the splinter with a hefty yank and stuffed the wound with a carbolic acid solution-soaked cloth. The horse got well, but it had left a huge, dimpled scar. In time, he went back to work — the horse, that is. When Dad was a young lad, he had visions of a heavyweight boxer. His training routine was running five miles each morning before going to work, then jumping into an ice-filled bathtub to toughen himself. He lifted heavy weights and dumbbells, did a fancy routine with Indian clubs and practiced boxing. He was practically ready to be accepted by the Golden Gloves when he was canceled out by the discovery that the sight in one eye was not normal (from an injury he had at age 4). He didn't realize his vision was impaired. When we were kids, I remember his challenging any likely opponent to "put the boxing gloves on" with him. He had a dozen pair of assorted sizes; he still did his dumbbell and Indian club bit. All of this equipment was in the closet behind the fireplace along with the shoe lasts. He was always performing for us; he walked a slack-rope that he tied between two cottonwood trees and showed his prowess by lifting heavy things. I saw him lift a horse, leaving its four feet dangling in the air. He used its soft belly on his shoulders to raise it. He lifted a tipped-over automobile off of a man who was under it; the man recovered and Dad was properly thanked for saving his life. He also entertained us with a cut tap dance that he called a "jig"; he'd put his hat on his foot and kick it up so that it landed right-side up on his head. He wanted us to be athletic, so he built adjustable bars for us to twirl on and hang by our knees and toes. Dad built a swing that was attached to the highest cottonwood tree branch. Only he could push us as high as its potential. We would ride it so high that we could look down on the roof of our two-story house. In teaching us to trust him, he would have us crawl up onto the porch roof, giving us a boost if we needed it, and tell us to stand up and jump off. He promised that he'd catch us, and he did. We thought this great fun, and we'd do it repeatedly.

Another skill that he shared with us was shooting at targets with a .22 rifle. We became quite accurate. He invented games like "shoot the lineup of pebbles from on the railroad track" and "shoot at marbles to make them jump from a starting line to the finish line." The one who shot the least number of times won. This usually took place while he was on the railroad duty, waiting for the tanks to fill for the steam locomotives, in both Ravenna and Lang. He later pumped at Cantil and Cameron, north of Mojave. Sis and I were introduced to gymnastics. We learned cartwheels, handsprings, bend backs, splits, high kicks, head stands, and to walk on our hands, etc. For a few years, no one could keep us right-side up. Even at school, we spent recess upside-down. The teacher told us it wasn't nice for boys to see our bloomers. We wore dresses only, in those days. The dress I best remember was an orange pongee that Mom made. I had worn it to light the Christmas tree candles; I bent over a lighted candle reaching to a higher one when the belly of this dress caught fire. I shrieked; Mom came running with a ladle in hand from cooking something, saw my belly aflame and knocked the breath out of me, slapping at the flames. She got them out, saw that I was breathing again and went searching for the ladle. I think it landed on the mantlepiece. Mom wasn't about to have me give up that dress after she worked so hard. I was then learning embroidery and had just finished outlining a duck in blue thread on a white background, and I basted it over the burnt hole and continued to wear it to school. Around the House

I remember Mom sewing pretty dresses for us. She sat at the treadle machine at night and sewed by lamp light. I overheard her getting many compliments about how pretty she dressed us. Sis and I would be dressed alike with colors being reversed. She made the patterns herself by holding a newspaper up to us and cutting it away. She had some creative ideas; she'd make trimmings of reversible ribbon and organdy roses, hand-gathered lace, etc. We were lucky having such doting parents. On one occasion I begged for a dress that was in the Sears Roebuck catalog. I wanted it for an upcoming program. It was black satin trimmed with ecru lace, rhinestones down the front. It cost $10, and in those days, and average store-bought dress was $1.98. I got the dress and thought I was one of the Astors. It was completely out of sync. The nearest sheriff's office was in Newhall. Dad was appointed the deputy sheriff in this area (as if he didn't have enough to do). He became good friends with the Los Angeles sheriffs and many lawyers. In fact he got so friendly that one night each year they were invited to one of Mom's chicken-fried dinners (as if SHE didn't have enough to do). The round dining room table was expanded so everyone could sit around it. We kids helped Mom with the serving. She raised and butchered her own chickens, cleaned them, cut them up and fried them, and served them along with every scrumptious thing she could muster. After they were well sated, Sis and I had to sing, recite poems, etc. After each number they threw handfuls of coins at us. After that, Mom served her delicious homegrown apple pie. On her last trip with a load of pies, she stepped on a roofing nail. She was off her feet for a few days; she deserved the rest, but [it was] an unfortunate way to earn it. She healed fine after much TLC from Dad and us. Dad did the cooking during her recovery, which he did several times when she was ailing. She nearly died from having the measles, and she often had migraine headaches. Mom certainly had plenty to do. Besides cooking three huge meals a day on the big, black Majestic wood-burning stove to feed the family plus all of the hired help, every weekend she had to cook extra amounts. Friends and relatives piled in on us every Sunday and always timed it to include mealtime. They thought that because we lived in the country, every food item was home-grown and thus cheaper. They didn't know about her weekly grocery shopping trips to San Fernando for groceries. I accompanied her most times to babysit the younger one or two who rode along. She'd buy 100-pound sacks of flour and sugar, for instance. In those days, a grocery clerk did the running around the store to fetch each item on her grocery list while she stood in one place and read from it.

Often, on the way, we'd have a flat tire or two. We'd just sit and wait for someone to come along and patch it for us — and pump it up, too. We had to travel the road through Soledad Canyon. I counted 28 creek bed crossings. We kids enjoyed the sloshing and splashing. One grocery item Mom read off of her list was cake decorations; she asked for mouse turds! [Ed. note: "Mouse droppings" was the vernacular for chocolate vermicelli used as decorations on cakes and buns.] Our home was the standard outpatient care recovery unit. Every relative who had a physical problem came to the ranch to recuperate. All of Mom's sisters took their turn. Ida, the oldest, was plagued with many problems and had several surgeries. But Nettie's food, fresh country air and fresh milk cured them all. In summer, Ida and I slept out on the porch. One moonlit night, she decided to walk to relive her misery. She'd mumble and curse; [it] awakened me, then I watched her trail off to the cow barn in her long, white nightgown. It gave me a spooky feeling. I was about 8 years old. Mom's No. 2 sister, Bertha, we later decided, was suffering from childhood malnutrition. She brought Sis and me the most pretty, feminine gifts each time she came. She became my second mama. She kept house for the family while Mom was away birthing one of the babies. She lived past 80 years old, as did Ida. I barely remember No. 3 sister Ruth, Dad's favorite. He said she had such a sweet disposition. She died at 22 years of age from having strep throat — quinsy — and having it lanced.

No. 4 sister Minnie, the baby, was very pampered, even as an adult. She had a mania for things "gunglina." She was very petite, beautiful and was asked to be in movies along with Mary Pickford and Clara Bow. She was Mom's only married sister at the time and lived with us while Ralph "Uncle Lang" Langley was away on location. He was a set designer and builder for Universal Studios. He walked me through many sets after working hours. He did in his 50s (?) of cancer. Minnie died at age 60 from heat [cq] problems. They had two sons. Ralph George, No. 1 son, was a hero bombardier during World War II; he later contracted multiple sclerosis. His wife, Kelly, was a brilliant secretary. Both contributed much to earn their space on this planet. No. 2 son, Walter Lambert, was an excellent carpenter finisher [finish carpenter]. He did delicate wood work. He is married to Linda. When I was 10-ish, I was privileged to spend a part of my summer vacation in the city. One I recall was a stay with Aunt Minnie and Uncle Lang, who lived in Lankershim (now North Hollywood) in a small rental court, as it was then called. Ralph Jr. was a baby and was teething. One night, a noisy, loud thunderstorm awakened Ralph Jr., plus he had developed a temperature. He cried, fussed and wailed unmercifully. So Mama and Papa decided it was time to consult a doctor. While they were frantically trying to find a phone number, the lights went out. The scene was mass confusion, looking for a candle, etc., and it struck me wrong. I cried — loudly — and wanted to go home right now. Incidentally, Ralph Jr. was born with the measles. Mom had an Uncle Lambert Heim, an alcoholic, politician, and inventor of the ironing board cover spring hooks that hooked the cover tightly. He spent several "drying out" sessions with us. One time he arrived very drunk, much to everyone's disgust. That night he vomited all over the floor of the upstairs bedroom, and the next morning he expected Mom or one of us to clean it up, but she just handed him a wash basin of water and some old rags and sent him up to clean it himself. Later when Uncle Emile sold his Bee Ranch, he was generous enough to give each of his sisters $500 — a fortune then —; this Uncle Lambert persuaded each of them to invest in Julian Oil. They followed his "sage" advice and they all lost it. Julian Oil went broke. It was interesting to watch the scurrying for the Los Angeles Examiner each day to watch the stock market fluctuate. The paper was delivered to our Rural Route mail box daily.

One day the paper had headlines four inches high that read, "Bullets Rain in Acton." This was during dad's sheriff days. He captured our ex-hired man Paul, who had run off and had broken into the Heffner house, a very swanky weekend type. He had cooked, slept and lived in it until one day Dad got suspicious of smoke coming from it mid-week. There was Paul, having a high old time for himself, pretending he was royalty. Dad, being a stickler for law and order, did his bidden duty and took Paul to headquarters, which was in Newhall. We later learned that Paul was sent to the insane asylum, but Dad, in capturing him, never fired a shot and never again trusted headlines. Back to ailing relatives. The most serious one was Uncle Albert Emile Platz, the younger brother of Dad, who had persuaded him to Pasadena from Eureka. He had been working on the Gates estate in Corcoran, irrigating huge acreages of hay makings, probably alfalfa. The water was assigned to each farm, and they had to use it when their time came, or do without. Many times Al's turn was at night, and he would open the flood gate from the canal and flood the fields, working long hours, sloshing around in knee-deep cold water. He caught pneumonia and was convinced that a cure for all ailments was to fast. He went days with nothing to eat, only drinking water. Then he acquired tuberculosis, so where did he turn to? Eugene and Nettie on the ranch. He became bedridden. Dad made him eat, put his cot outside in the sunshine, and provided him with snap-top sputum cups. We kids played closely around him and learned later it was highly contagious. The school nurse kept an eye on me since I was so skinning then, a sign of TB. Then dad remodeled the chick brooder house into a decent living quarters and sent for Al's family, Aunt Lois Shepherd and son Al Jr., better known as Boop-saly, a cute, blonde, curly headed 2-year-old. Dad completely supported his brother and family until Al succumbed. One day Dad was busy in the lower alfalfa field and when he arrived back at the house, Lois and son sneakily had made arrangements to go to her parents' in Petaluma. Dad was surprised, shocked and angry. She could have at least said thank-you and goodbye. Uncle Al was interred at Rose Cemetery between Burbank and Glendale. Mom and Dad even paid for that. Lois' mother contributed to a part of it. Green Eggs and Hooch On our ranch, the northeast corner was four acres of assorted grapes — a very productive vineyard. Each year at harvest time, the hired men would pick the ripe grapes — a mixture of five or six kinds —, load them onto the horse-drawn flatbed wagon and haul them to the huge, circular redwood vat in our front yard. Everyone would wash their feet and stomp the juice out of them; then the juice was drained off and stored in huge redwood barrels that were lined up next to the bunk house, under the same roof. I thought the stomping was great fun, even though I fell flat into it several times. It stained my clothes. I drove the team and wagon for Dad many times in the open fields, so I was assigned the job of driving a load of grapes to the vat. But havoc reigned. The road near the yard was lined with fence posts — old railroad ties and barbed wire. I was too short to the left, ripped up the wagon bed and tilted a fence post on a sharp bend in the road. I was about 10 years old at the time.

After the grape juice fermented properly, our ranch became very popular. All visiting men were escorted to the "winery" and had their fill of wine. Occasionally, Dad would bring a water pitcher-full to the house for company. One day, after everyone went outside, there was some left in the pitcher on the dining room table. Buddy, age 5, decided to finish it off. Later, we looked for him and found him curled up half under the back porch. We called Dad and he carried him around and he was giggling all the while, trying to awaken him. He gave up and put him to bed to sleep it off. Bud never cared for alcoholic drinks his entire life. During Prohibition, Dad's friends and the proprietor of the Ravenna grocery store, Walter Couse, talked Dad into allowing him to brew whiskey on the ranch. So Walter moved into the second upstairs bedroom and slept alongside the still that they set up. It was a mystery to me: What was all of that paraphernalia that was toted upstairs? Hundred-pound sacks of grain were hauled up periodically. Then there were strange "shirring" sounds. I was never allowed to peek in. When a stranger drove into the yard, Mom got such a scared, frantic expression on her face. She'd hurriedly start to fry onions or burn sugar to influence the aroma from the upstairs odors. One fine day, Dad had taken a horse pulling a single plow into the chicken yard and plowed it up. He used a long metal rod to poke into assorted areas of the softened earth, hoping to find the several gallon containers of whiskey he had buried there. Our neighbor, Paul J. Otto, lawyer, on his weekend visits to his Shangri-La, always made a point of visiting us with the ulterior motive of getting a drink of Dad's 180-proof whiskey. I saw them trailing off into the wooded area beyond the chicken yard. I sneaked behind them, hiding behind trees. They came upon a two-story lug box arrangement; the top box had a hen sitting on a nest of eggs. Dad gently lifted the top box off, and the lower box had a fifth of whiskey hidden in the leaves. I think the setting hen enjoyed the ride. They saw me and swore me to secrecy until now. Dad's alcoholic sheriff friends complimented him on his fine whiskey and were his best customers, instead of slamming him in jail. Did I mention that Dad also had a railroad job besides dairying, farming and brewing? To that he added a chicken business. Mr. Good, former owner of the property that is now North Oaks in Santa Clarita valley, who was a carpenter, built a great, long chicken house and that brooder house that became Uncle Al's final home. They started out with 1,000 baby chicks. Mom was in charge of regulating the temperature. It was my job to go read the thermometer periodically and herd the chicks around to keep them from bunching up. It seemed that they wanted to stand on top of each other. Mom always scraped her shoes off as she left the brooder. One time, something felt funny; she'd stomped on a baby chick.

The Farm Bureau man came around monthly to advise us. One Saturday he urged us to attend a local meeting at the schoolhouse. We were late. First, Dad had to medicate and walk a horse that had a bellyache from eating green apples. I was the only one who went to the meeting with him. The highlight for me was the demo of the green-yolked eggs. We learned that egg yolks will turn any color according to the color you add to their feed. As the chicks grew older, we had some delicious young cockerels to eat. The hens grew into very productive layers. Gathering eggs was fun, but to scrape and clean their roosts was hard, dirty work. The eggs were carried to the milk house, the one where the milk separator and butter making — molding it into 1 pounds — was done. The eggs were candled, cleaned, weighed in a tiny scale to decide the grade, and crated and sold. Dad's sister, Bertha Beckert, somehow fell into the job of preparing them for shipment. I often helped her. She, like Dad, sang while she worked. Each afternoon she'd go upstairs to practice. She played her saxophone, guitar or mandolin for hours. She and Charlie, her son, were in demand to perform at our local entertainments. She acquired a boyfriend named Rollo Fryer. Every Saturday she'd roll her hair in kid curlers to frizz the hair around her face; she had a bun in the back. We had a lot of fun together. She gave me my very first music lesson on steel guitar, a cheapy the folks sent for from Sears, Roebuck & Co., then in Chicago, Ill. She was the only relative worth her weight, a hard worker. The ranch had a large orchard of apples. Dad boxed them and drove them to an outlet in Newhall. One trip I'll never forget. They were carefully graded and boxed; he loaded them into his open-air milk truck and drove down Mint Canyon. At the Oaks Garage — now Le Chene restaurant — an oncoming car made a sudden, unsignaled left turn in front of him. He slammed on his brakes to avoid a collision and the whole load of apples flew up and rained down on him, filled up the front seat and scattered all over the road. I can't remember how we arrived at the scene of the mishap, but I started gathering up the apples and Dad said, "Don't bother. To hell with it," and we all trundled back home. His back and head were thoroughly pelted with apples. He laughed about it later. Another annual crop was turkeys. They were raised strictly as Thanksgiving and Christmas gifts for our city friends and relatives. Butchering and dressing them was the hardest part. After de-feathering and cleaning them, we loaded them into the sedan, dressed in our best and go a-calling and presenting [sic]. WE were usually fed a meal of store-bought food, different for us and a treat. This was to a group of friends that we did not see but once a year. School Days When my cousin Al Klaner, Dad's oldest sister's only child, visited us, we learned a bit more about some distinguishing facts about our family tree, such as Dad's mother had an uncle who was a 6'7" guard in Napoleon's army; and Dad's father, Henry Xavier Francis Joseph, was part of the uniformed entourage at the original dedication of the Statue of Liberty in New York, representing France. His French uniform is being preserved by descendants (cousins) in New Jersey. The original road to Palmdale followed along the present Carson Mesa Road along the railroad track. When the Mint Canyon Road, now called Sierra Highway, was dug out of the mountains south of Vincent (then a major railroad point), the road building department rented two of our horse teams plus our dirt mover, called a Fresno [scraper]. It was so exciting to anticipate the shortcut to Palmdale. At the time, Palmdale was a major railroad town with a one-room school, Palmdale Inn hotel, tavern, café, a small grocery store, gas station and Fehrensen's Drug Store, with a few scattered small farms surrounding it. It soon gained a Doctor Brockett, preceding Doctors Senseman and Snook. The road between Palmdale and Lancaster was lined on both sides of the road with locust trees, which were manually watered via water hauling truck whose faucet extended from the truck to the trees. There were eight miles of alfalfa fields on the west side of the road. The trees were all removed to widen the road. A pity. Oops — December 2, 1988, 6:31 a.m.: Space shuttle Atlantis just blasted off. I haven't missed seeing one of the shuttle events — via television, that is.

School! On my very first day of school, Dad drove me to Ravenna to board the train with friends, get off at Acton and hike the trial to the red brick school house on Cory Street (1921). My mother, with her kin, also attended this school 15 to 20 years earlier. I wore a new dress with white hat and carried my lunch in a shiny, new lard pail. I loved school. While in the first grade I remember my teacher, Mrs. Alexander — a hefty, freckle-faced redhead — called on me to correct an eighth-grade boy in his reading. Again she used me to detect a funny odor in the schoolroom. She sent me outside and ordered me to take five deep breaths, step inside and announce the odor I detected. Proudly, I said, "cigarette smoke." I don't think I was very popular after that. The seventh- and eighth-grade boys were young men, some much taller than Mr. A. Her way of disciplining them was to approach them from the rear while they were studying, grab their two ears and give them a good shaking up. The element of surprise was her weapon. My way home from school each day was via horse and shay. Mom, after lunch, rested, then fixed herself up pretty — she wore ratted puffs over each ear — and after Dad harnessed the horse and hooked up the shay, she trotted to school to bring me home. The first hired school bus driver was Mrs. Long, who lived in our present Mayor Calloway's house [former Nickel home, 31823 Crown Valley Road, built 1891 — Ed.] He used his open Model "T" Ford. It was so high off the ground, I needed a stepping stool to get aboard. One afternoon, he arrived to pick us up to take us home; he pulled up to school and stopped, but the right front wheel went right on and rolled into the junipers and sagebrush. The Ford slowly sank. Mr. Long wore a funny tail hat; he reminded me of what Ichabod Crane might have looked like. We walked home.

Mr. Long's bus route was to the Fryer home in Soledad Canyon, now Cypress Park [approx. 7601 Soledad Canyon Rd. — Ed.]. By the time we reached the Petner Ranch — Paul Otto's place, north end of Thousand Trails — we kids were double-decked, hanging onto running boards, etc. One time, W.W. Roth was sitting on the door, hanging onto the top, when the door flew open. He was grabbed and saved by Caroline Fryer. For a while, Jim Fryer Sr. drove us all to school — no mishaps. Mr. Williams, Jane's father, developed a rig to haul us. It was similar to a jail on wheels. It was a big, black box with a row of benches along the side, no windows, with a latticed metal gate in the back, the kind I've seen on animal cages. If his paycheck was late, he'd refuse to stop at the railroad crossings. Big, brave me! I tattled on him and he was fired. Mom got into the bus driving business using our Woody station wagon. That developed into regulation buses, but at first she had to purchase her own, and Dad's railroad job furnished the gas. She became one of the state of California-recognized drivers with her 23 years, no-mishap term of driving. A broken ankle forced her to retire. I recall one stormy day, she couldn't reach the school for the p.m. run. The river crossings were too high. So she hiked along the railroad track to reach the school to inform them. No phones then. There were soft places in the railroad bed, and she sank to her knees in one hole. Imagine — walking another mile in the rain with all of that heavy mud plastered on her legs. Several times she lost her shoes in the suction. More later about her being a fun traveling companion. While in the second grade, Miss Gerchicoff was an art major. I did a water color of a branch of apple blossoms against a pale blue sky. When the annual Los Angeles County art exhibit took place, she represented our school with that painting. I never saw it again. In the fifth grade, I struggled with fractions until one day, like a flash of light, I finally understood them.

From the third through the eighth grade, I had the same teacher, Miss McClaflin. I can't say enough good things about her. She had ultimate discipline. Along with teaching all subjects to eight grades, she developed a showmanship quality in us. All holidays, she put on programs that included us all. She coached us in plays, drills, singing and reciting poems. We each had to learn long poems throughout each school year. She totaled the most students who, when in high school, made the honor society. She should have been awarded a gold medal. Instead, when she was forced to retire, the school board gave her an insulting sendoff, all because one member in particular didn't like her looks. She was tall and very thin, had toothpick legs and buck teeth. She even bothered to replace her teeth for the school board. It still didn't help her. We had to real warped people on the school board at that time. Earlier, Dad was on the school board; he helped make good things happen. He insisted the teachers' wages be increased from $25 per month to $35 per month. If a married teacher became pregnant, he was for it, instead of being fired. A lot of students were the children of the Mexican, low-paid rail workers. At that time, there was a row of houses along the railroad track, south of the depot, that housed many of the families. Some would come to school with no lunch. Dad and Captain Haisch put a stop to that. Each before-noon, Jane Williams and I walked to Captain Haisch's General Merchandising store and received sandwich makin's, took it back to the girls' anteroom and built sandwiches for the lunch-less ones. Dad sold some milk locally; in fact, he had quite a long milk route to deliver to on his way to his railroad job daily, a 10-quart. I bottled it occasionally. Anyway, he furnished as much milk as needed for the school lunches. At that time, he used glass, one-quart bottles with "Platz" etched on them, capped with unlabeled cardboard, snap-in caps. King of the Road Long before Uncle Al died, Dad and I took a train trip to Corcoran to visit him. I was 4 years old then. Al met us at the Corcoran depot in his topless flivver and drove us to his bunk house where there was room for us to sleep. We all ate in the mess hall. There were several long tables that seated dozens of the harvesters, and we were served by Chinese cooks and waiters. On our last meal there, the baker presented me with a pumpkin pie with my name written across it in the cake icing. On our trip home, Dad dressed me in my best dress, an off-white wool sailor dress with a box-pleated skirt. On the train, I fell asleep and had a "piddle" accident. The red plush seats transferred color to my white skirt. Dad did his best to remove the stain. He never went anywhere without taking one of us along. When we grew up, he would take a grandchild. My No. 2, David, had several unique experiences while riding with him. His railroad job had him on the road at all hours. All of the local residents were aware of this, so they drove cautiously, expecting Ed Platz on every curve in the road. He gained a reputation of owning the road. When he heard the train whistles from Ravenna, that signaled him as to the train filling up with water; thus he had to make a beeline to start the pump. He was on alert 24 hours a day for 33 years. The pump that he first used to fill the water tanks was on the north end of the Heffner ranch. He was asked to keep the Santa Clara River free of debris, as this was the stream that flowed to the railroad water tanks. He earned $25 per month, and with his knowledge of gasoline engines, this developed into a full-time job. In the later years, when other railroad pumpers along the Southern Pacific line ran into mechanical problems, when all else failed, they summoned Ed Platz to solve their problems. He always did. He had a psychic rapport with engines. On one occasion, he was sent near Bakersfield to solve a problem. All he did was look the engine over, then announce, "There's water in the fuel." He was right. Later, the railroad drilled a private-owned well near Ravenna and installed a larger engine. After that was when Dad became the No. 1 traveler on the road from home to Ravenna. All local residents soon became aware of Ed Platz racing up and down the road day or night, depending on whether he heard the train whistle that meant "stopping to take water." While he was still using the pump on the Heffner ranch, one of us kids usually went with him to clean out the ditch. While he waited for the pump to warm up, we'd scout the stream, and I became intrigued with small species of assorted water life such as frogs, toads (there is a difference), water bugs that skittered on top of the water, a big flat one that lived under the water, minnows — later known as the endangered species of three-spine stickleback —, all kinds of water grasses, reeds, cattails, and small plants that bloomed in assorted colors. The moss was the biggest culprit; we fished it out so that it wouldn't clog up the water system. While we would wait for a small reservoir to fill, we sat on rough benches in a Chinese-built log cabin and played cards, mostly solitaire, on a makeshift table. Dad was a dead shot with his one good eye. He hunted for deer every year on Mount Gleason. He often saw mountain lion, several kinds of cats — lions, cougars, fox, etc.; I still have a fox neck piece, popular in the '20s — that he trapped along the "crick." One hunting trip, his friends and he arranged a hunt to the mountain. A heavy fog set down and totally confused the direction back to the ranch house. Luckily he made it home OK, but he was worried about the other hunters being lost, so he took his gun and fired three shots into the air, and this gave the others direction. Later, there was much conversation over the three shots bringing them back. I felt that he was a hero.

The basis for our schooling was to be patriotic. We saluted the flag each morning after lining up for calisthenics, followed by singing patriotic songs, then on with lessons. Strict discipline was a natural state of being; never gave a thought to being prankish. If anyone gave an inclination of being unruly, they had not only to deal with the teacher and parents, but with the other students who would shun them. One adventure that stands out in my memory was an offer from Mr. Lebo, who invited the entire school to his home to hear Calvin Coolidge's acceptance address. He lived on the acreage my folks bought later, at the end of Platz Road. All of us students walked to his home, about one mile. The family squeezed us all into his small living room. We practically sat on top of each other while the Lebos assumed their easy chairs and he fiddled with that monstrous radio set to tune the correct station in. The set had many dials to synchronize to get the squealing out. The voice came over the air very thin and tiny, but we could distinguish each word. After returning to school, there was much discussion and we were made to feel that we had been part of a historic event. Out in the World In our growing, older years, high school age, the Christian Endeavor of the Presbyterian Church became the center of our activities. Aside from the Sunday evening gatherings, we had bunco parties and progressive parties; [the latter] consisted of walking from house to house receiving part of a meal at each home. We started up Crown Valley Road and ended up two miles down Soledad Canyon Road — of which I walked backwards the entire two miles. We organized camp-outs in lovers' lane, usually the starting point of a hike to the top of Mt. Gleason. I was with the group that hiked to the top two times in one month. At the very peak was a 60-foot watchtower, which we all took turns climbing so as to get our first view of Catalina Island. The forest ranger and his wife resided in a small cabin near the tower. He related interesting stories of his experiences, including being on the lookout for mountain lions, whose tracks were plainly visible. He had us sign a guest book and appeared to be appreciative of the "visitors." Also, we looked forward to Friday-night choir practice at the home of the Carter family, led by Ruth, usually. She taught us good harmony. W.W. Roth was my boyfriend, so he and I were paired off to sing duets as "special music" for church. In fact, a C.E. convention was held in Palmdale; all of the San Fernando Valley bigwigs attended. Guess what the special music was! W.W. and I sang "Ivory Palaces" again (and again, etc.). One Saturday a.m., our group was to meet in front of the Newton home (now Taylor Land real estate) [subsequently razed; it stood at 32003 Crown Valley Road, where the Acton Market Country Store was built in 2013 — Ed.]. While the crowd gathered, Wesley Newton dared me to climb inside of the Bradford bread box — a huge box where they bakery stored the bread for the shopkeeper, Mrs. Newton. I did it! I had to double up so he could close the lid. I started to panic and he decided to let me out, only to discover the lid was locked. I could hear them scrambling around to locate the key. It took a while. I could have suffocated except for my using the keyhole to breathe through. After marring W.W., we lived in an upstairs apartment in Glendale. I had hours to entertain myself, so I walked all over the town by myself. I found the most enjoyment in strolling through Forest Lawn, studying up on copies of famous art works. We also attended the night classes at Biola for a short time. I had to walk there daily to seek out a few cents to buy something for the evening meal. Nausea from my first pregnancy was my constant companion the first four months. We originally met Mr. Stonier through his Christian work at Monte Christo prisoners camp. We held Sunday evening services there once a month. We transported a pump organ to accompany the singing.

One special evening I remember was taking Raymond Debauch and Howard ? along, who rode in the back of the pickup truck. At that time, the road was very narrow and curvy. It seems that Howard and Raymond were sitting on the truck bed sides, across from each other, when Howard withdrew a live snake from his pocket and pointed it at Raymond, who let go and fell overboard backwards. The yelling from them was constant, so when Howard yelled to stop, we ignored him until we had traveled on for several curves. Howard finally got our attention when he tapped on the window to stop. Seeing no Raymond, it shook us up, not knowing what to expect. Turning and driving back, we found him dusting himself off in the middle of the road. He landed in soft dirt and was thrust overboard by our taking the proper curve too swiftly. W.W. could never stay with anything, so we soon moved into Palmdale to live and work for Fred (Grandpa) Roth in his lumber yard. My one piece of furniture was stored in the lumber yard, where a leaky roof allowed my cedar chest to fade, bubble and blister. I still have it. My folks presented it to me when I became engaged. We shared the one-room apartment by my sleeping on a lumpy sofa and he slept on the floor. I had only one smock for Sunday wear. One Saturday I laundered it and hung it to dry in their backyard, and in the morning it was gone. The nine years we were married, he worked a new menial job every few months, and we moved 11 times from one old, miserable shack to another. We divorced April 12, 1945, the day FDR died. Then I and the four kids were alone for 10 years. Among the several odd jobs I took were laundress for Joe Scaroni; mail messenger from Acton Post Office to the Acton Depot; part-time librarian; substitute bus driver for my mother; accompanied a male quartet; played in the Melody Four dance band; sewing for Mrs. Newton (she had two levels of hip bones); and chauffeured Mrs. Haisch to have her shopping sprees and nails done. My most fun that 10-year period besides enjoying my children was belonging to Fad of the Month Club, making assorted craft items; and driving to Lancaster one night a week to play violin in the Lancaster Little Symphony Orchestra. Then I was offered by the Dahlenburgs to be a waitress trainee. I fell right into it and started to bring home real money. My $88-a-month child support didn't buy breakfast. On the four weeks' vacation from working the Crest Café, I switched to Wilson's [13136 Sierra Highway, later the Alamo Church — Ed.]. Then my life really began. An Artful Life Before I start on my wonderful life with Jim, I'll describe my two years before I first married W.W. I flunked history my senior year at A.V. High School, so my folks had me transfer to Franklin High near my cousins, the Beckerts, to repeat my senior year. Best thing I ever did, being exposed to many new courses like millinery, pattern making, costume designing, fashion art, etc., which led me to enrolling into costume designing and dress making classes at Frank Wiggins Trade School on 16th and Hill Street, 7th floor (now called Los Angeles Trade Tech). My goal was to get a job in the costuming department at Universal Studios, where my Uncle Ralph Langley was opening doors for me. This was Depression time, and there were no jobs available, so I ended up packing pears in the Martin shed at Littlerock. I camped in the orchard with the Roth family. Our cook stove was homemade, a 5-gallon can with the handle end removed and a hole in the other end for a chimney. Evenings were spent by sitting around a campfire singing hymns and slapping mosquitoes. I worked for a month at 35 cents an hour. On my last paycheck, I was cheated out of one-half of my earnings, with no recourse. Every Monday at 4 a.m., Dad took me to the Acton Depot to board the early passenger train to Los Angeles. I rode, no charge, because I had a railroad pass of Dad's. I arrived in time to go to school and stayed midweek with the Beckerts. Friday evenings, Charlie and I always went to the top floor of the P.E. building, 6th and Los Angeles streets, to the auditorium to rehearse with the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra; Bronenburg conducted. After rehearsal, I took the 5 [cq] car back to the Los Angeles Depot and re-boarded the late train ride back to Acton. Dad met me at 11:30-ish p.m. I tried to be helpful to Ma over the weekend. I'll never forget that huge stack of ironing that was waiting for me. One time I clocked my ironing time. A 7-hour stretch, using a gasoline-heated iron that needed pumping up to build up the heat. I loved to iron men's shirts. I graduated from Ben Franklin H.S. June 1933, sixty in the class. We girls wore formals for the ceremony. Mine was a two-piece, blue organza that I bought in May Co. — the only May Co. at the time, on 8th and Broadway. Midweek, Charlie and I sought out many other night school orchestras. Charlie's driving the brown Model "A" across town gave me scares and thrills. He cared to squeeze between the street car and the boarding zone full of passengers waiting to climb aboard, among other daredevil exhibitions. One rainy night, in crossing town, he slammed on the brakes suddenly, and we pivoted on the spot and were heading the wrong direction when we stopped. Our orchestra (L.A. Symphony) gave a yearly concert and played for many special occasions. On those occasions I always felt sorry for the drummer, transporting his instrument. Several performances were transported on the P.E. [Pacific Electric] Red Car for free. I remember going to Covina for a concert especially. Fun! We had monthly parties in various homes. One I especially recall was at an old-fashioned house having small rooms with gingerbread trim everywhere. We always west up our instruments and played fun music. Being squeezed throughout the house, the violin and I occupied the kitchen. The owner was an elderly horn player who was a movie extra and had hair dyed brilliant blue, so as to photograph white. Another party was another home east of L.A. and they served jiggers of port wine. Being very thirsty, I chugged it down like water and nearly choked to death. Another party was at the home of a college professor who lived in Burbank. His home was loaded with art objects. It's the first time I saw an actual fresco painting, high on walls in each bedroom. My classes at Frank Wiggins were 8 a.m. to 12 noon, so my girlfriend Beatrice Land and I, who lived near each other and had the two years of classes together, spent the early afternoon going to matinees. On Wednesday we could see four pictures for one price, 25 cents admission. We'd get a street car transfer, dismount on Broadway near our choice of movie house (a choice of many), see our pictures, re-board the 5 car and go home. One extremely eventful time was the Long Beach earthquake. Mary Beckert was on the second floor of the French Hospital on College Street, having birthed Jimmy two days earlier. Her bed rolled across the room. She was so frightened that she got up and out of bed — strictly forbidden in those days. Flat on your back for 10 days was enforced. She insisted on going home, so an ambulance was hired to bring her home. As the earth quaked, I was standing in a doorway, looking out to the backyard, and saw the fruit tree bend to the ground, back and forth. Charlie happened to be flat on his back on the ground under a car and didn't feel a thing. Mary's mother, Mrs. Betty, was keeping house at the time. So we all shook, rattled and rolled for days after. A few days later, we took a ride to see the major damage. Unbelievable. Houses had shaken off of their foundations and two-story apartment houses' walls fell away, leaving bedrooms, etc., exposed. Frank Wiggins School was closed until the buildings were inspected. It had developed a multistory crack.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.