|

|

Standard Oil Co. of California: The First Fifty Years

The Standard Oil Co. of California | September 1929

|

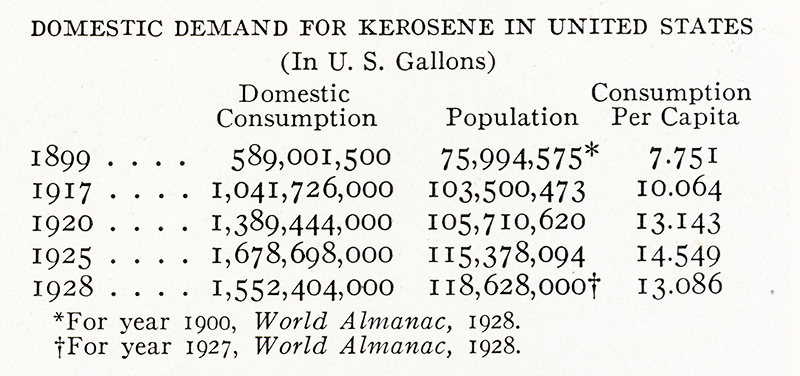

THE FIRST FIFTY YEARS. As the sun appeared to sink in the Pacific Ocean out from the Golden Gate on the tenth day of the current month, this Company rounded out its first half-century of existence. For this September 10th was the fiftieth anniversary of its birth, counting as its natal day the date of incorporation of the erstwhile Pacific Coast Oil Company, the bud which opened into a handsome blossom — the Standard Oil Company of California — if we may speak in such flowery terms of ourselves. Brief details of this metamorphosis will afford enlightenment that may be desired: The Pacific Coast Oil Company was formed in 1879. The old Standard Oil Company, which in the early eighties began establishing agencies on the Pacific Coast, purchased the stock of the Pacific Coast Oil Company in 1900. The latter company retained its corporate name until 1906, when it was changed to Standard Oil Company, identifying it with the New Jersey company, of which it had become a subsidiary. Then, in 1911, in compliance with the United States Supreme Court decision generally referred to as the "Dissolution Decree," it became the Standard Oil Company (California). As such it operated until January, 1926, when, merging with the Pacific Oil Company, it became the present Standard Oil Company of California. In the beginning the Pacific Coast representation of the old Standard Oil Company was exclusively a marketing organization; the agencies engaged solely in the distribution of Eastern refinery products, principally kerosene. The Pacific Coast Oil Company pioneered in petroleum-producing activities in California, and in refining. About the year 1890, the Pacific Coast Oil Company entered into an arrangement to sell its refined product to the Standard Oil Company. The next outstanding development was the aforementioned purchase of the company itself by the Standard Oil Company, which was immediately followed by a campaign of expansion in every phase of the oil industry. That campaign has been a continuous performance, and today, thirty years later, finds it still in progress. These columns have dealt with it from time to time in accounts of the Company's development activities in its va rious departments. As noted, new oil-sands have been discovered by it, refineries and pipe-lines constructed, tank steamships and motorships launched, and in virtually every phase of the petroleum industry new procedures have been initiated and put into practice by the Company. The Standard Oil Company of California, through its more than five hundred products, its personnel and service, speaks for itself as to the part it plays in this vastly changed world of today. All that might be written of its activities could at best be but a faint echo of the actual performances whose beneficial effects are realized wherever the Company serves. So instead of discussing them, on this occasion — the Company's fiftieth anniversary — it seems more fitting that our narrative hark back to beginnings — back to the days of the horse-drawn vehicle, back to the days when some of our special agents rode forth on bicycles to interview prospective customers, back to the days of kerosene, Eureka Harness Oil, and Mica Axle Grease. Facts bearing on these times may prove entertaining and, affording data for comparison with what is now existent, will make most evident the growth of the Company, and in addition set forth the tremendous changes in life and habits that came to the Pacific Coast with the advent of the internal-combustion engine and electrical development. An attempt to reflect this evolution pictorially is submitted in the old-time photographs accompanying these notes, augmented by the front-cover drawing. Necessarily meager (as our text also must be) because of space limitations, it is a sketchy presentation of kerosene-lamp and horse-and-wagon days, leading up to the advent of the automobile, which is represented by specimens of the Company's early acquisitions in the way of motor equipment. The use of horses and mules continued long after the automobile had ceased to be a curiosity, and until automotive equipment came into general use, the principal products marketed by the Company were kerosene, axle grease, and harness oil — and certain lubricants. Our sales reports of 1887 give evidence that machinery was beginning to afford a profitable sales outlet at that time, for among the items one finds mention of Capital Cylinder Oil, Magnet Valve Oil, Eldorado Castor Machine Oil, and more than half a dozen engine oils, of which Re nown, Atlantic Red, and Solar Red are the best known. There was, however, even at that early date, some market for gasoline: the Company sold a "deodorized" stove gasoline and a higher-proof product for illuminating purposes. Also, benzine was marketed to cleaners and dyers. But until the motor car was well headed toward coming into its own, the product that bulked largest and was most widely used was kerosene — "water white." With this product (among the well known brands of the day were Pearl Oil, Pratt's Astral and Elaine Oil) the Company pioneered on the Pacific Coast, in Alaska, and in the Hawaiian Islands. Kerosene was virtually synonymous with Standard Oil to a scant population, comparatively speaking, scattered over a vast area notable for its wealth of undeveloped natural resources. The kerosene lamp has almost become a museum piece; it is a symbol of what used to be. "Kerosene has been electrocuted," someone with a flair for fancy phrasing has observed. Unquestionably the oil-lamp has been displaced by electric lighting, but this famous product of petroleum, which we of the Company have ample reason to regard sentimentally and with affection, is not dead by any means. Strange as it may seem, in the thirty years since 1899 the domestic demand for kerosene in the United States has increased about 163 per cent, while the percapita consumption has gained from 7.751 gallons to 13.086 gallons in 1928. The peak was reached in 1925, when 14.549 gallons per person were used. Those figures are excerpted from the following tabulation, compiled by the Company's Department of Economics: The many new uses for kerosene that have come with the invention of oil-burning devices — and here should be included tractors that use kerosene as fuel-are in part explanatory of these figures. Further explanation may lie in the fact that kerosene continues to factor as an illuminant, even in the larger cities. Who cannot recall having encountered an array of red lanterns, with but a few yards between units, extending for blocks along streets where excavations for sewer or gas lines, underground electric transmissicm systems, or pavement replacements were under way? Such present-day demonstrations of the use of kerosene are always more or less in evidence in big cities and in fast-growing suburban districts. Those lanterns do not burn for an hour or so after sundown, but all night long. One such job in a week may call for burning hours and volume of light equaling the month's requirements of a fair-sized village, with many farms thrown in, as light was used in the kerosene-lamp days. Of immeasurably greater significance than the kerosene statistics already cited is the following fact: in 1880 more than 75 per cent of the average refinery yield from crude oil was kerosene, while today kerosene accounts for but 6 per cent. The difference in the percentages directly reflects the progress that has been achieved since those days when kerosene was the most and the best we had to offer; it speaks not only for this Company's progress, but for that of the petroleum industry and of the entire civilized world. Deduct the 6 per cent of kerosene, and the remaining refinery yield is made up of the many products of petroleum that are inseparable from the functioning of the modern world.

|

CSOW Time Book

1887-1889

CSOW Stock Certificate 1901

SCV History Moment

Early Oil & Gas Production in Calif. (Video 1985)

Standard Oil Co. History to 1929

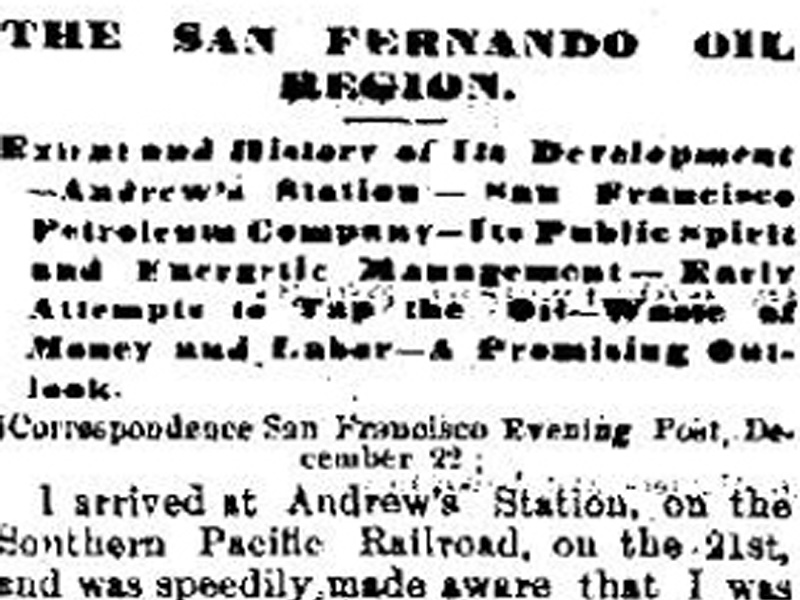

Description Jan. 1877

Description May 1877

Description 9-26-1882

Oil Tank Const. & Death 1883

Mentryville 1885-1891

CSO Hill 1883

Oil Works ~1885

The Pico Field 1890

PCO Hill ~1890s

CSO Jackline Plant

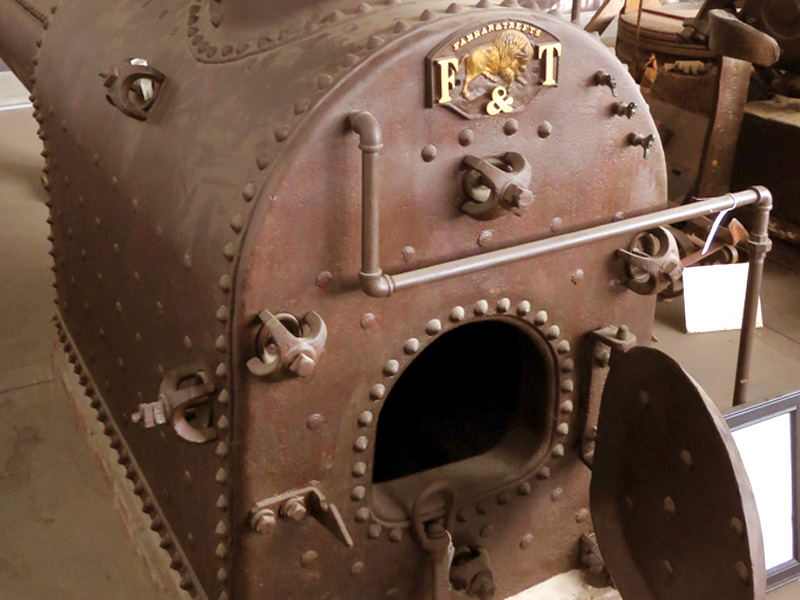

Farrar & Trefts Boiler

New Boiler 1893?

Mentryville 1890s-1900s

Reamer Patent 1900

Machine Shop 1910

Machine Shop 1910s

Natural Gas-to-Gasoline 1913/14

Mentryville ~1920

Pico No. 4, 1931

CSO Jackline Plant

PCO Jackline Plant Remnants

Darryl Manzer at Firehouse ~1961

Darryl Manzer at Field Office ~1961

Pico No. 4, 1961

Darryl Manzer, L.A. Times Story 1962

National Survey 1963

PCO Jackline Plant Removal 1974-75

CSO Jackline Plant 1974-75

A.C. Mentry Blacksmith Forge

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.