|

|

[NEXT] [PREVIOUS] [CONTENTS] [SEARCH]

55. Fights and Feuds

|

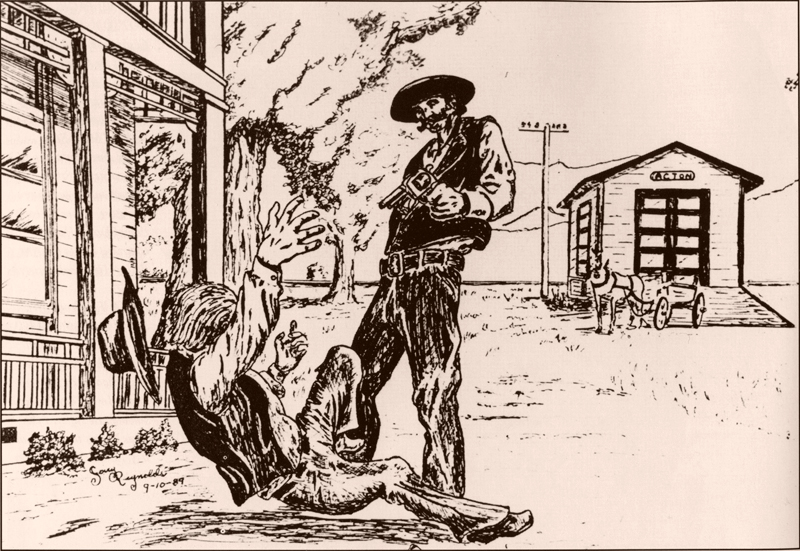

Long ago there stood a massive oak tree right on Railroad Avenue between George Campton's general store and the lofty Hardison and Stewart warehouse in downtown Newhall. Old timers such as Irene Ruiz McKibben recall with a certain gleam in their eyes that this was where the lives of rustlers, robbers and other anti-socials came to a sudden and abrupt end. Law-abiding citizens would awaken in the morning to find some ornery cuss swaying gently from a length of hemp rope after being visited by the neighborhood watch. The first resident watchman in this valley was William W. Jenkins, whom we have met. Jenkins, a California Ranger and later county undersheriff, went to his grave with seven slugs in his body (though he didn't die from his wounds). McCoy Pyle, who operated a cattle spread near Val Verde and found the fabulous Bowers Cave (Chapter 5), became a constable but got himself killed in a shootout near Castaic Junction just before the turn of the century. Other constables included Ed Pardee, who ran the livery stable and whose house has since been transplanted to Heritage Junction; and Carl Sischo, operator of the valley's first gas station. Ed Brown was perforated by twelve bullets while investigating a "domestic dispute" in Railroad Canyon. Curiously, Brown was buried by the Ku Klux Klan. John Samuel Pilcher broke up bootleg stills, raided illegal gambling establishments at Sandberg and survived a half-dozen gunfights, only to be brought down in June 1925 when his deputy accidentally dropped his revolver during a raid. The pistol discharged, sending a bullet right between the constable's eyes. He was dead before he hit the floor. During 1926 the Sheriff's Department opened Substation Number 6 at Sixth Street and Spruce (San Fernando Road), with six deputies commanded by Captain Jeb Stewart to patrol the far reaches of the Upper Santa Clara. Their territory initially stretched all the way from Chatsworth to the Antelope Valley. About the time the great Castaic feud was settling down, another battle erupted in Acton. This one had far-reaching implications that nearly cost a district attorney his job and brought the most famous criminal lawyer of the age, Earl Rogers, to the area. A great many of the early settlers of Acton were of German descent, from upstate New York. A leading citizen of this frugal, hard-working, well-behaved faction was William Broome[1] — farmer, church deacon, school board member and honorary mayor.

During the 1890s newcomers began to arrive, mostly from the south. Their leader was W.H. Melrose, called "Rosy" by his friends. Melrose was a big, fun-loving Kentuckian who was addicted to practical jokes, besides being quick on the draw and deadly accurate. He easily ingratiated himself with county officials, and on May 10, 1898, his wife, Flossie A. Melrose, became postmistress. The trouble seems to have started when Broome's snorting, snarling pit bull attacked Melrose's good-natured dog Llewellyn, prompting Rosy to shoot Broome's offending animal. Broome had Melrose arrested, but at the trial the local school teacher, Minnie Boucher, backed the Kentuckian. Naturally, the German element tried to get Boucher fired. Broome even branded her a "railroad whore." Acton became an armed camp and the schoolmarm was transferred. On January 20, 1903[2], Melrose and Broome faced each other on Acton's dusty main street. The guns roared and William Broome dropped with five well-placed bullets in his chest. The trial was a sensation, with the famous Rogers as counsel for the defense. Before it was over, district attorney Fredericks — a close friend of Melrose's — had been accused of corruption, and Broome's body had been exhumed with a news photographer on hand. Each of three trials ended in a hung jury. Ultimately the charges were dismissed. But the bad blood remained, and gunshots rang out in the night around Crown Valley for years to come.

1. Broome was actually a late-comer, moving to Acton from Arizona in 1900. 2. Reynolds erroneously said Feb. 28, 1905. See this. ©1998 SANTA CLARITA VALLEY HISTORICAL SOCIETY · RIGHTS RESERVED. |

William & Harriet Farmer Family Pre-1890

Wanted Poster for Hattie Farmer's Killer 1890

Farmer Murder Questioned 1903

Pollack: Harriet Farmer Murder

The Hunt for Harriet Farmer's Killer

Reynolds: Fights & Feuds

Pollack: Revisiting the 1903 Acton Feud

Graves of Hattie Farmer, Nancy Melrose

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.