Webmaster's note.

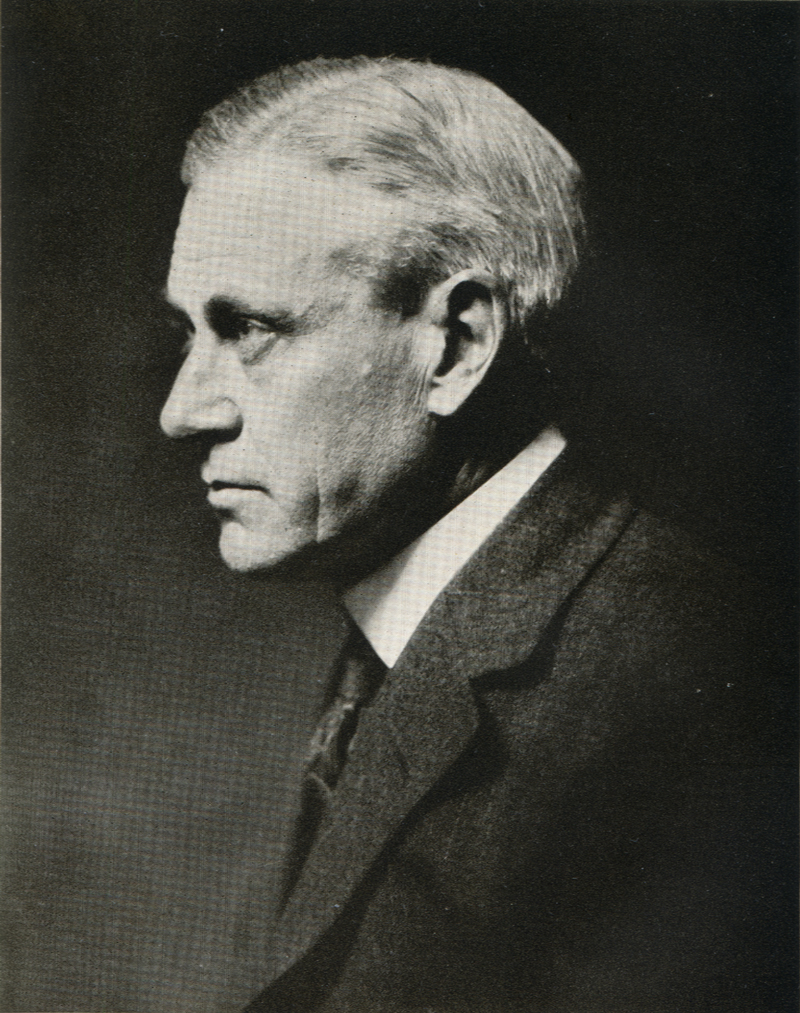

Stephen T. Mather in 1915, upon his appointment as Assistant to the Interior Secretary.

|

Stephen Tyng Mather, his biographer tells us, was 47 years old and restless. He needed a new challenge. A Chicagoan with a degree from the University of California at Berkeley, he'd made his first million off of the natural resources in Tick Canyon, in the eastern Santa Clarita Valley, where prospectors in 1906 had discovered colemanite, a form of borax. Mather invested his profits wisely and now, in 1914, could count himself among the idle rich. But Stephen Tyng Mather didn't know how to be idle. So he founded the National Park Service.

Congress was ever an obstacle, but otherwise America was ripe for it. The war in Europe had shut off the popular vacation spots where Americans could stay in good hotels and dine at fine restaurants while seeing the sights. The Western United States had none of that. It had the natural wonders, but instead of amenities it mostly had mud. Vacationers often had to pay tolls to logging and mining companies to access the country's few and far-flung national parks, and thanks to Henry Ford, there were far more vacationers now.

Woodrow Wilson needed another wealthy self-starter who could abide a paltry government salary while getting the parks in order. He had one inside Franklin K. Lane's Interior Department who'd been tasked with the job, but then Wilson pulled the man away to set up the Federal Reserve System. So when a letter lamenting the sorry state of the nation's parks landed on Lane's desk in late 1914, the secretary can't have been surprised. And then he saw who sent it. Stephen T. Mather, the big-time borax manufacturer from Chicago who hobnobbed with politicians as easily as he scaled 10,000 feet of Western peaks every summer. Lane recognized the name. "Dear Steve," he wrote back, "If you don't like the way the national parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself."

And so he did.

With Horace Albright at his side to handle bureaucratic matters — something Mather abhorred — "Steve" was sworn in as Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior on Jan. 21, 1915, and on Aug. 25, 1916, Wilson signed the National Park Service Organic Act into law. A Bull Moose (Teddy Roosevelt) Republican in the tradition of his abolitionist father — at a time when TR was racking up enemies left and right ‐ Stephen Mather was an anomaly. Under three presidents and five cabinet secretaries of different political stripes, he would organize and expand the park system, serving as the first and only Director of the National Park Service until a debilitating stroke forced him to retire in 1929.

Introduction

By Gilbert Grosvenor, President, National Geographic Society

From "Steve Mather of the National Parks" by Robert Shankland. New York: Alfred A. Knopf 1951.

More than thirty-two million people visited our National Park system in 1950. By broad, well-paved highways, they gained ready access to the scenic grandeur thus preserved for them. Within the confines of our twenty-eight National Parks and many National Monuments, at suitable intervals they found comfortable lodges, restaurants, camp sites, and picnicking areas to make their stay pleasant and to enable them to enjoy nature's revelations.

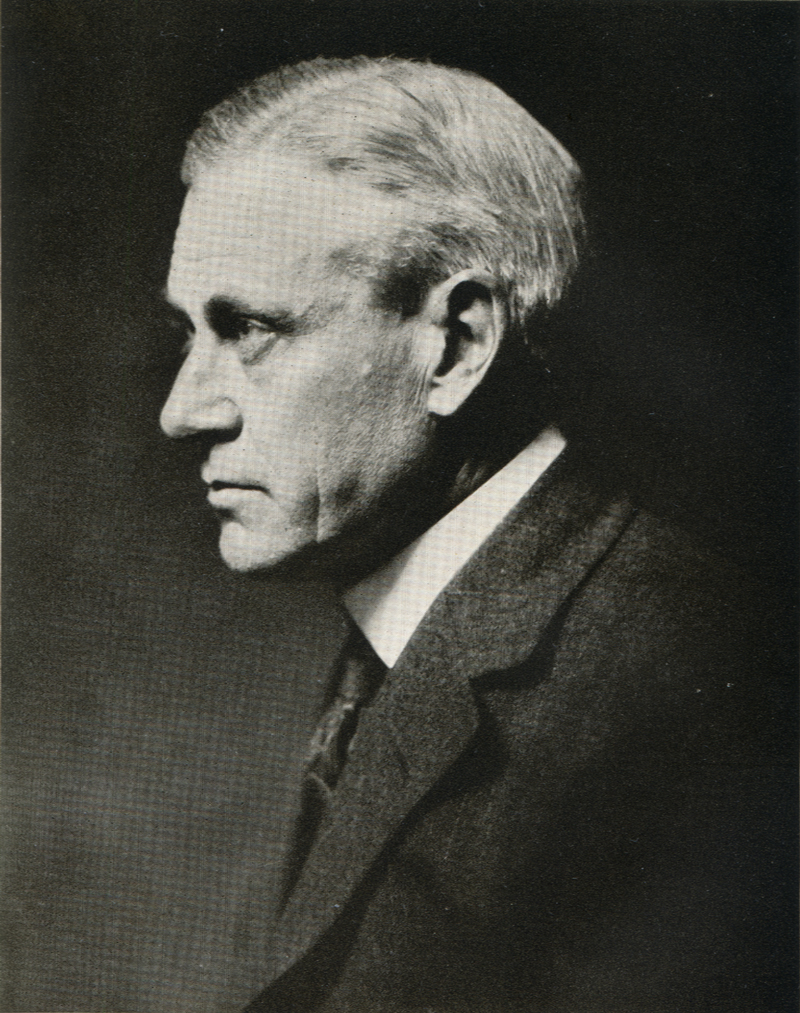

On what would have been Stephen T. Mather's 65th birthday, July 4, 1932, identical bronze tablets were dedicated at several national parks to commemorate the man

who founded the National Park Service. The tablets, which include a bas-relief sculpture of Mather, were sculpted by artist Bryant Baker in 1931

and fabricated by Gorham Manufacturing Co.'s Bronze Division. The inscription reads: "Stephen Tyng Mather / July 4, 1867 / Jan. 22, 1930 /

He laid the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas shall be developed and conserved

unimpaired for future generations. There will never come an end to the good that he has done."

|

Many hands have joined in the common effort to build up our unparalleled National Parks system. But the untrammeled vision, steady purpose, and indefatigable labor of one man stand out above all else. To Stephen Tyng Mather, father of our National Park Service, the people of the United States owe a lasting debt of deep gratitude.

In 1914 Mr. Mather, an influential and wealthy Chicago industrial leader, visited some of our National Parks in the West. He was dissatisfied with the manner in which they were conducted, and he wrote a letter of protest to Washington. Soon he received a reply from Franklin K. Lane, Secretary of the Interior, and an old college chum at the University of California, urging him to come to the Capital, take charge of the parks, and "run them yourself."

Mr. Mather accepted the challenge. With the rank of Assistant to the Secretary, and the salary of a present-day stenographer, he went to work on January 21, 1915. Two years later the National Park Service was founded, with Mr. Mather as its director.

In 1915 we had only a few National Parks, and they were poorly managed — without central authority, without adequate appropriations, without sufficient accommodations for visitors, without efficient personnel, without almost everything (except, of course, the natural wonders themselves) that makes a trip to the National Parks the delight it is today.

Congress lagged far behind the new director's plans in appropriating funds cto carry out his progressive ideas. So Mr. Mather dipped into his own pocket to advance the National Parks.

Scenic Tioga Road, for example, was the only entrance across the Sierra Nevada into Yosemite National Park. It was a toll road owned by a mining company. Aided by some California friends, but contributing most of the money himself, Mr. Mather bought the road and gave it to the government. Today tens of thousands of visitors to Yosemite enjoy this spectacular approach.

Mr. Mather gathered many groups of men and women — journalists, businessmen, and those prominent in public life — often giving dinner parties in Washington and in the different states, at his own expense for four or five hundred people, to arouse interest in the National Park program.

His guests heard addresses and saw amusing skits based on the preservation of our scenic wonderlands. By his genius for friendship and his astonishing energy and enthusiasm he fired their interest in the movement and put the parks on the solid ground they occupy today. He took a leading part in adding many new National Parks — Grand Canyon, Bryce, Zion, Acadia, Lassen, Hawaii, and Mount McKinley — and through enabling legislation made certain the future creation of Great Smoky Mountains, Shenandoah, and Mammoth Cave.

The National Parks system that Mather brought about is an American innovation. No other country, not even Switzerland despite its world-renowned scenic splendor, had attempted to develop areas for public use along such lines. Many other countries have in recent years copied the American plan for National Park reservations.

On Mather's arrival in Washington, Secretary Lane invited me to lunch to meet him.

Mather's first words to me were: "I'm getting up a party to spend two weeks in the Sierra Nevada and I want you to join us."

Before I could answer Lane added: "You have sailed me in your small yawl many hundred miles around Cape Breton and Prince Edward Islands and have shown me some of the best scenery and people of the East. Now I want Steve to show you what we have in California."

Stephen T. Mather's mountain party of 1915. At head of table: Stephen T. Mather. On his left: Gilbert Grosvenor; Mark Daniels; Clyde L. Seavey;

W.F. McClure; Horace M. Albright; Ty Sing, cook; Henry Floy; unidentified ranger; Peter Clark Macfarlane; Frank Ewinsg; Ben M. Maddox; unidentified ranger.

On Mather's right: E.O. McCormick; Frederick H. Gillett; Burton Holmes; Henry Fairfield Osborn; Emerson Hough; George W. Stewart; Bruce Johnstone;

Dr. S.E. Simmons; Ranger Carl Keller; Frank Depew, assistant to Burton Holmes. Identifications by Gilbert Grosvenor.

|

There were fifteen in Mather's party the next July: Congressman Gillett, later Speaker of the House and United States Senator; Emerson Hough, author of "The Covered Wagon"; Henry Fairfield Osborn, President of the American Museum of Natural History; and others who had been selected for their ability to help his park plans. We had a glorious two weeks in the mountains; every night we camped on a new site, and slept in the open, no tents being necessary. The birds were as beautiful and sang as sweetly as in the East; the flowers were as fragrant and colorful; the mountains much higher; and the superb white-granite canyons and domes of the King and Kern and Yosemite unlike anything I had seen in the East. We made the thrilling ascent of 14,496-foot Mount Whitney, the highest point in the United States.

Two of the party amused us by wearing heavy veils suspended from their hats from sunrise to sunset, explaining they were sensitive to black flies and mosquitoes, of which we saw none.

Whenever we passed a waterfall, Mather shouted: "Here we get a free shower." He and the hardier members of the party leaped off their sweating horses, stripped, and in a few seconds were shouting and slapping under the icy water from snowfields just above.

Mather enjoyed this "treat" four and five times daily. His vitality was amazing. He seemed immune to fatigue. His solicitude for the comfort and pleasure of every guest endeared him to all.

I am proud to say that the first donation of funds by a national organization to aid Mather's program was the twenty thousand dollars subscribed by the then young National Geographic Society in 1916 to help preserve the great red trees of the Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park. Later, the society contributed again to the saving of the Big Trees. These contributions (and, of course, Mather's own, which were large and frequent) started a considerable flow. Those, for instance, of Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ran into many millions, not including the more than twenty millions devoted to the restoration of colonial Williamsburg, now within the boundaries of the Colonial National Historical Park.

In this volume Robert Shankland not only chronicles Mr. Mather's achievements but offers penetrating insight into the man's love of nature and his deep-seated desire to preserve its more spectacular and awe-inspiring phases for the delight of future generations of Americans.

Mr. Mather's daughter, Mrs. Edward R. McPherson, Jr., made available to the author a rich store of material that had been preserved in the attic of the old family home in Darien, Connecticut. There he examined vast quantities of old letters, scrapbooks, photograph albums, and documents, which threw new and detailed light on Mr. Mather's varied activities.

Mr. Shankland is to be congratulated on a conscientious and workmanlike accomplishment. He has written an inspiring narrative that also has great historic interest. The National Park Service is Stephen Mather's chief monument, but this book is another, and it is worthy of the man — which is saying a great deal.