|

|

Eyewitness to the 20th Century

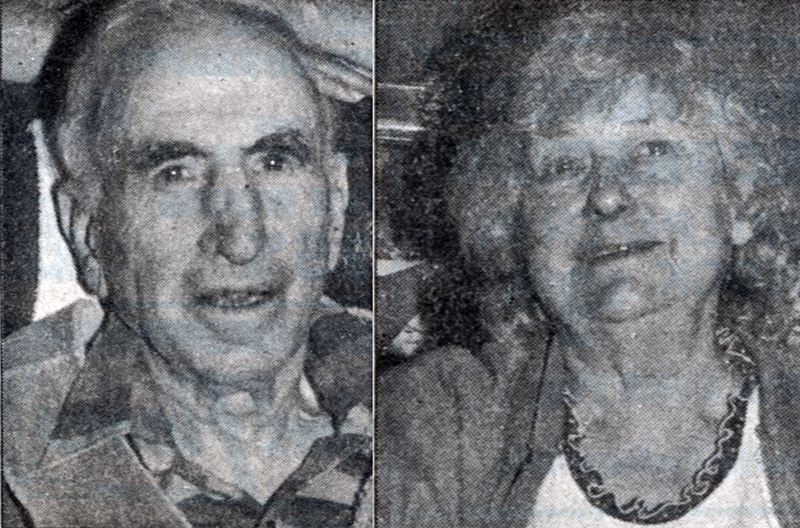

Andy and Camille Jauregui.

The Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise | Wednesday, December 19, 1984.

|

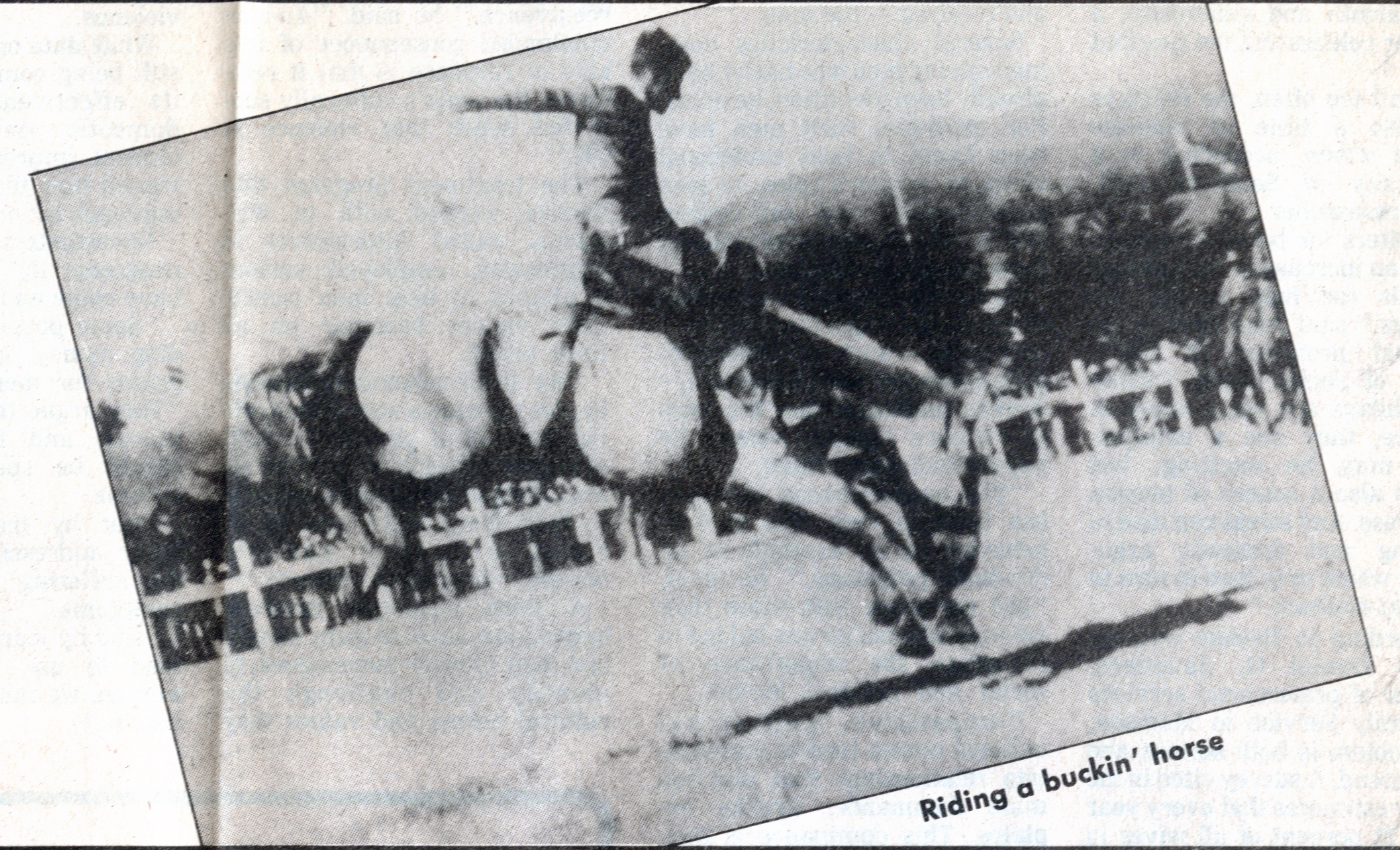

In a little red house off Placerita Canyon Road live Andy Jauregui — one of the greatest rodeo cowboys of all time — and his wife, Camille. The little house has been a drawing place for Western movie stars and young rodeo cowboys since the Jaureguis moved there in 1928, and was the site of the happy childhood days of the Jaureguis' four daughters. It is still a place of joy and laughter, especially when their daughters' families gather to dance on the patio and eat the Italian dishes Camille Jauregui learned from her mother. * * * Andy Jauregui is a polite man who says, "Oh, Jeeminy Cricket!" for an exclamation and "Ma'am?" if he misses a question. At 80, he has silver hair, dark eyebrows and sharp black eyes. His real name is Leandro, which is Basque for Andrew. Born in 1903, Jauregui wanted to be a rodeo cowboy as long as he can remember. He insisted on riding his horse the four miles to school rather than sitting in the horse-drawn buggy with his teacher, who boarded with them at the Jauregui ranch in Wheeler Canyon near Santa Paula. Jauregui wanted to be a cowboy, and cowboys did not ride in buggies. His first venture into public view came when he was 16. He rode in a makeshift rodeo put on in a ballpark by Jesse Stall, a black cowboy acknowledged to be one of the best cowboys in the business but prevented by racism from winning top prizes in rodeos. Years later, Jauregui would nominate Jesse Stall to the cowboy Hall of Fame, and the two were inducted in the same year. "That was the first guy I rode for, in a ballpark, was old Jesse Stall. He didn't have money enough to pay. I rode a little old buckin' horse, and when it was over he went around and passed his hat. I think he gave us $5 apiece. I was 16. "Of course, in them days there wasn't a lot of cowboys or rodeos like they do nowadays. A lot of shows travel all over the country. In the early days, when I was just a young fellow, it wasn't very easy to go. My dad, he'd complain about me — he didn't complain too much — that I'd ride at the rodeos, get on them old buckin' horses. "He'd sooner me do somethin' else, in a way, but he wasn't too much against something like that that we wanted to do. We were raised with livestock, breakin' horses." "I never got hurt from riding in a rodeo. The worst time I got hurt was when I hurt my neck when I was in the rodeo business, furnishing stock. I was riding this old car and run into the back of another car, and stuck my head in the windshield, and that arthritis set in. "One time I didn't have a car and I was going to go to a rodeo. I was about 18, 19 years old. It was a rodeo in Hemet. So, I got my dad to take me to the depot in Santa Paula. I went by train to Los Angeles and got on a bus in Los Angeles and went to Hemet in the bus, to the rodeo. "They wouldn't let me ride because I didn't have my own saddle. So, I got a job there on the ranch, an outfit I knew, and I worked there for, oh, maybe a month. Instead of being a cowboy, like I wanted, they sent me out there in the field cuttin' weeds with a hoe. I didn't think that was much of a cowboy's work." After a month of hoeing, Jauregui left to ride in a rodeo in a fair in Ventura. "I rode there, and I won some money there in bronc riding, and that got me started." From such inauspicious beginnings, Jauregui became one of the most successful cowboys in the rodeo and movie business. He worked in Western movies as a stunt man, doubling for stars such as Tom Mix and Richard Dix. "I was young and didn't know no better, I guess," said Jauregui about those days. In 1924, he got a job running the stables for a Western street in Newhall for Clarence (Fat) Jones. He and his new bride, Camille, moved to the Santa Clarita Valley, where they would remain. The street, known as the Western Hollywood, was located where the American Legion is now, on Walnut south of Lyons Avenue. The Jaureguis lived in a house they built on Arch Street. Camille Jauregui rode Fat Jones' horses all over the hills with her friends, and she and her daughters acted as extras in Westerns. Meanwhile, Andy Jauregui broke horses and doubled "heavies," or bad guys. After a few years, Jauregui got into the stock business and produced some of the finest animals in rodeo history, including Red River — a horse who won the Best Bareback Bronc award in 1960 and 1963 — and Square Head — a lame bull not even the best cowboys could stay on. The horse Joel McCrea rode in the Wild Bill Hickock Show was trained by Jauregui. In 1928, the Jaureguis moved to the ranch in Placerita Canyon where they live today. Until the Antelope Valley Freeway cut through the property, the site was used for film locations. Along with the freeway, the traffic and telephone poles which came with development have spoiled the scenery the Jaureguis remember. "There were no telegraph poles, nothing," said Camille Jauregui. "It was pretty. If they could have them buried under the ground it would be nice. They sure do spoil the scenery. It used to be so much fun to ride, but now, you take your life in your hands." Clark Gable, Will Rogers, Bill Hart, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and Harry Carey were among the people who came to the Jauregui ranch. Once, shortly after the Jaureguis had moved to Placerita Canyon, Clark Gable came by. "This old house was in not too good a shape," recalled Andy Jauregui, "just kind of throwed together, you know. We were talking and I said, 'Not much of a house — the wind blows through it.' And Gable said, 'You get Standard to sell me this land up here, and I'll build you a house that the wind won't blow through.' Yeah, he was a fine guy." But Standard would not sell, and the Jaureguis still lease their land, at 1928 rent. The house long since ceased to let the wind through. Will Rogers was another longtime friend. "Will Rogers used to come out here to the ranch. He had a polo field, and I trained horses at that time. I sold him a couple of good horses. And he had a place in Santa Monica where he used to rope calves. He was a heck of a guy, you know? One of the best men that I've ever seen." Camille Jauregui recalled: "Andy used to furnish calves and then go down there and rope with him. He'd buy the calves and then give them back to him. He was that kind of person." In the days when Andy Jauregui was "operating kind of short," he went to a big rodeo in Chicago at the World's Fair. The day before he left, he happened to be at Will Rogers'. While he was loading his horse into the trailer, Rogers said, "Now, if you get in trouble back there, don't let them fellahs take this horse away from you." "He meant if I didn't make any money," that Rogers would wire him money so Jauregui wouldn't have to sell the horse to get back home. "He was that kind of guy, you know." Jauregui won the first day in Chicago. His friends called up Will Rogers to tell him, and Rogers announced from the stage of the Coliseum, where he was doing a show, that a prunepicker had gone back and won. "Prunepicker" was the derogatory name Easterners gave to Californians in those days. One day, Bill Hart and Andy Jauregui met in a blacksmith's shop in town. At the time, the Jaureguis owned only a pickup truck. Bill Hart's car was sitting outside, and Hart asked Jauregui if he had $5 on him. "I says, 'Yeah, I guess so.' He said, 'Let me have it.' And I gave it to him, and he says, 'You can have that car, if you want.' "Oh, the kids had fun with that car," said Camille Jauregui. Andy Jauregui was a champion steer roper in 1931 and world champion team roper in 1934. "My favorite was calf-ropin' and ropin' steers." Jauregui's rodeos traveled all over the country, from Madison Square Garden to Honolulu. He operated the rodeos in what is now the Saugus Speedway. Jauregui was inducted into the cowboy Hall of Fame in 1979, an unusual honor for a man still living. Joel McCrea, the Western movie star, nominated him. In 1983, Jauregui was named to the Western Walk of Fame [in Newhall], along with Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. He was known to be generous. Noureen Baer, one of Jauregui's daughters, remembered that when Jauregui lent a cowboy money, he signed a blank check and told him to be honest and honorable and not to worry about it. The Depression did not affect the Jaureguis severely. As Camille Jauregui recalled: "Living on a ranch, you know, we had our own milk cows, we had chickens, we had everything we needed. And plenty of animals to butcher so we could have our own meat. It's the same with all ranchers or farmers. So far as the Depression goes, the only thing that affected was the rodeo business, and there weren't as many rodeos. He (Andy) was doing stunt work for pictures then." During World War II, soldiers camped in the Jaureguis' fields with a searchlight to spot airplanes. "We'd invite them over to have dinner with us," said Camille Jauregui, "and the Catholic boys would go to church with us." "We had a blackout once. Andy happened to be gone." Mysterious noises outside kept Camille Jauregui and her daughters up all night. "I'll never forget it. We might have had flashlights, but they told us not to use them." They discussed calling the soldiers "to see what the heck was going on." When day broke, Camille said, "I'm going to look." She stepped outside and saw their dog in the rocking chair on the porch. "Every time the dog would move, it would hit the side of the house." The soldiers were well-behaved. Jauregui had told them to come to him if they needed help but to show respect for his daughters by staying away from the house. The girls made fudge and cookies and handed them to the young soldiers through the window, though. "Some wrote to us after the war was over," said Camille Jauregui. "One from San Francisco kept writing to us until just a few years ago." The Jaureguis' four daughters, Julain, Noureen, Joann and Andreena, all grew up on the ranch. Camille Jauregui recalled they used to roll up the Jaureguis' big rag rug to dance. She always supervised. "One moonlit night," Camille said, "a fellow that was working here, a good friend of Andy's, hooked up the team, put some hay on the wagon, and they went around the field singing away, just singing. They really had a good life then. "But things have changed now. Nothing's the same anymore. Maybe in other states it's not so crowded." Jauregui sold his rodeo business 10 years ago, when his health no longer permitted him to continue. He will turn 81 on February 10. "It's a long time to be pounding a body, I guess," he said. "Oh, it's not been bad. I look back at people that I worked with in the business, and now there's not many of them left." * * * Camille Jauregui was born in the wine country of Northern Italy, in the little town of Barone in the foothills of the Alps. When she was 4, her father went to California. After six years, he came back, thinking he would stay. "He stayed there eight months and then he couldn't stand it anymore. He said, 'We're going to get away from here. There's going to be a big war. We're all going to go to California!'" So, the family left just before World War I broke out. They took a train across the Alps and sailed from Isle de France to Ellis Island, then boarded a train for California. Camille Jauregui remembers the train trip. "That was before they had the bridges across the Mississippi and Missouri, so the trains would be put on ferries. They allowed us to get out and watch, and it was quite thrilling, this great big river. Coming across, they got their signals mixed up, the train going west and one going east. And it was at night. Oh boy, all of a sudden — the trains didn't hit, they stopped in time, but everybody fell down. I remember skinning my legs and hurting myself a little bit. No one was hurt badly." Camille felt sad to leave Italy, but she missed her older brother, who had gone to California three years before. She would miss the old country. "I missed a lot of things, especially the seasons. In the wintertime, when we had snow, in those days there were no skis or anything like that, but we had toboggans. We had a lot of fun in the wintertime. Our town was on a hill, and we'd go way up to the top so we could just slide all through the town. "North Italy was wine country, and of course everyone makes their own wine. Some of them that have plenty, they sell the wine. When they stomp the grapes in the big troughs, oh, that was when we used to have fun." Her family settled in Moorpark. Her father found work with a large farmer and grew beans and hay. "Before we'd go to school, my father and my oldest brother both had teams and we had to clean the barns and fix the bedding. If we didn't do it then, we did it after we came home from school. And we had our own chickens and rabbits and pigs. My dad made his own sausage. It was real good sausage. "When you're ten years old and you don't know the language and all, it's a little bit hard. The teachers were real good. The kids didn't like foreigners, as they called us." The family stayed three years in Moorpark and then moved further out into the countryside, where many of the people were Italian and Portuguese. Camille Jauregui remembers the big celebrations the Portuguese would put on, with "plenty of food and dancing and singing." "Everybody seemed to have a horse. We went to school in a horse and buggy. "I loved school. I hear the neighbors here complain: 'It's so boring.' But I say, 'You'll look back on these days and say, "Why didn't I enjoy it?"'" She wanted to be a teacher and had the chance to stay in town and continue her schooling, but her old-fashioned mother would not allow it. "She was afraid something would happen to me." She was 16 when the family got their first car, but she hated to drive. Her oldest brother, Charles, was drafted in World War I but was never sent overseas. "But we sure missed him. Those were hard times. We all were farmers, you know, and there was a lot of work on the farm. All the neighbors pitched in and helped each other. I had to help. My schoolmates had to help." She first saw Andy Jauregui when she was standing in line at a Ferris wheel. "I saw him go by, and I asked my younger brother's friend — I knew that he knew many people around there — 'Hey, who's that?' He said, 'Oh, that's one of the Jauregui boys.'" They met at a dance in a garage in Saticoy, and flirtation developed into courtship. They married when Camille was 20 and moved to Newhall. The Jaureguis will have been married 60 years in June, and Camille Jauregui has advice for young couples: "Try to get along. It's a give and take thing. If you really and truly love each other, you have to work at it. "It's not easy. Some people just don't want to work at it. When it gets a little bit tough, they divorce. Sometimes there's no other way. "To me, it depends on how much you love each other and how much respect you have for one another. "Live within your means. We've both been very good about that, not going overboard about buying things. But a number of them, oh, they make a little money, get a big car and all this stuff. Some of them can make it, some of them can't. We've never been like that. We've saved our money for our old age, so we could have something. "To see him ride, that was my pleasure. To watch him ride and watch him rope horses."

This is the final biographical profile of The Signal's series of "Eyewitness to the 20th Century."

Download individual pages here. Clipping courtesy of Cynthia Neal-Harris, 2019.

|

Story by Andy Jauregui 1935

Andy Jauregui & Wm. S. Hart 1938

Andy Jauregui Bio by Noureen Baer 1978

Profile: Andy & Camille 1984

Jauregui's 1934 Saugus Rodeo Ribbon

Branded Pitcher

Tim McCoy in The Man from Guntown 1935

The Ivory-Handled Gun 1935 (Mult.)

FULL MOVIE: The Gunman from Bodie 1941

Gene Autry in The Singing Hill 1941

Forbidden Trail 1941

Eddie Dean in Tumbleweed Trail 1946

Randolph Scott in Trail Street 1947

Gene Autry in Strawberry Roan 1948 x3

Alias Jesse James 1959 (Mult.)

Canadian Club Ad 1969

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.