|

|

Historic Headlines:

Remembering the St. Francis Dam DisasterBy Michele E. Buttelman

Signal Features EditorSunday, March 11, 2001

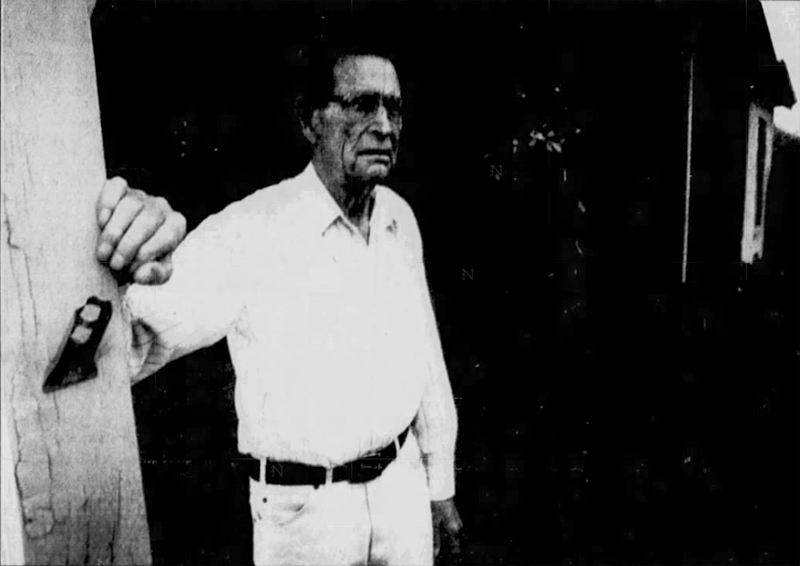

Bailey Haskell in 1995. Photo: Shaun Dyer/The Signal. Click to enlarge."Great St. Francis Dam Crumbles"

"Great Wall of Water Sweeps Sleeping Victims Into Eternity"

"Death Flood comes In Darkness"

"Dead May Number 400"

"Living Hunted in Debris!"

"Flood Death Toll Grows"The bold, black headlines echo down through the years, staring up from the fading, crumbling newspapers that carried the tale of death and destruction to their readers.

The second worst disaster in California history began on March 12, 1928, near midnight, in the remote San Francisquito Canyon area of Saugus. The St. Francis Dam failed at 11:57:30, a time pegged to the loss of electricity from the Southern California Edison transmission lines to Lancaster. The lines were located 90 feet above the dam's eastern abutment.

The dam's reservoir of 12.5 billion gallons of water poured down the narrow canyon, initially in a140-foot-high wall of water, and swept nearly 500 men, women and children to their deaths. In California history, only the 1906 San Francisco earthquake killed more people.

It was a disaster of epic proportions, one that remains largely unpublicized and unknown, today.

As the flood carved out a path to the sea, it lay waste to Castaic Junction, Piru, Fillmore, Santa Paula and Saticoy before emptying into the Pacific Ocean, more than 50 miles away, near Ventura."Death and Destruction Carried by Great Flood Wave When Big Dam Breaks"

"Many Bodies Remain Buried in Debris as Death Toll in Catastrophe Still Mounts"

"Fillmore Funeral Chapel Stacked With Bodies of Victims of the Flood"After the catastrophic failure of the dam, the newspapers, including The Signal, dispatched reporters and photographers to the scene of the tragedy. They filled their pages with photographs, interviews with survivors and lists of the dead.

Tales of horror and heroism were documented for days, and in some instances weeks, after the deadly dam collapse.

Remarkable tales of survival and tragic tales of loss were reported in the Fillmore American of March 15, 1928. "Shot his Way Out Thru Roof of House Saved by Sycamores" was one such headline.

"Frank Maier and his wife and three children, residing on (a) ranch below the Bardsdale bridge, had a remarkable escape. As the waters swirled in around them, they made their way to the attic. Here Frank shot a hole through the roof, through which he passed his wife and two of the children to the roof. As he was about to follow them with his son, the house began to move, it was caught in a little circle of sycamore trees, where it rocked from side to side, without turning over or being carried away. The house floated, like a leaky boat, the mark showing that there had never been more than eighteen inches of water in it, when it dropped back to the ground."

Another story in the same paper reported, "How Old Man Koffer Swept to Safety on Mattress of his Bed." Demonstrating how writing style and political correctness have advanced through the years, the story read:

"Old Man Koffer was saved. And the term old is not used lightly or slurringly, for he isseventy-four . He and his wife, also aged, lived on the Carter ranch above Fillmore. The waters caught them as they slept. And that is about all that Old Man Koffer remembers. For when he realized where he was, he was on his knees, clinging to the mattress, his old wife gone. A few awful moments and the mattress and its aged occupant swirled out to one side and landed in the Illharaguy lemon orchard, where help came to him."

In another tragic report, a man was able to save his baby, but his wife and four other children "swept by, crying for help that could not come."

"Wastes Scarred by Fearful Hand of Death Stretch Under Leaden Skies in Land of Misery"

"Corpses Flung in Muddy Chaos by Tide of Doom"

"Desolation Stalks Where Fertile Fields Once Held Happy Homes, Now Hurled Into Oblivion"

"St. Francis Dam Disaster Most Appalling"Newspapers of the day were not shy about placing opinion on their front pages. The Fillmore American wrote one of the most scathing pieces on the disaster:

"Just as the ominous thirteenth of March, 1928, was being born, Death, mounted on a wave of swirling waters, seventy feet high, and beginning at a crumbling dam high up in San Francisquito canyon, rode in devastating wrath to the sea. Sweeping through the most fertile valley in the Southland. And in his wake he left death, and devastation, and ruin, where a short hour before his passing people slept in peace, security and happiness.

"The story of the breaking dam has greeted your eyes from scores of newspapers pages before this one reaches you. How the big $2,500,000 dam, built on the insecure foundation of a great city's greed for what did not belong to it, crumbled as the result of faulty designing and hasty construction. Engineer Grunsky was right. That great dam built in the center of the canyon, withlight-flung wings to the soft earth sides of the mountains, was an ‘old woman's apron.' And the strings broke and the result was a hell of swirling waters that took life after life, until its fury was stayed in the waters of the sea."

The St. Francis Dam was the brainchild of William Mulholland, the manager and chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Mulholland had designed the aqueduct from the Owens Valley that brought a reliable and steady supply of water to Los Angeles. Water politics between the city of Los Angeles and the farmers and ranchers of the Owens Valley were strained after many in the northern valley felt that Los Angeles had "stolen" their water. A group of ranchers had tried to dynamite portions of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, others had captured a spillway and shut off water to the aqueduct for a brief time. Mulholland wanted a local reservoir to hold an emergency water supply that could sustain Los Angeles for a year in the event that an earthquake, or other calamity, severed the aqueduct.

The Signal, a weekly paper in 1928, first reported the tragedy on Thursday, March 15.

"One of the worst calamities that ever happened in Southern California took place Tuesday morning at about 12:30 a.m. when the great San Francisquito Canyon dam broke and sent a wall of water crashing down the canyon, sweeping everything in its path to destruction. ... The loss of life was appalling, coming as it did, in the dead of night, without any chance of escape..."

In a Los Angeles area paper, the tragedy is reported in the dramatic style of the day: "Death and devastation continued last night to stare back from the sodden wastes of Santa Clara valley upon ahorror-stricken world, mute with the knowledge of appalling loss of life and property in the greatest disaster in the history of Southern California."

"Total Loss in Lives and Property Is Still Very Incomplete"

"Responsibility for Disaster Undoubtedly Up to Los Angeles"

"Flood Indictments Hinted"

"Dynamite Theory Now Advanced As Cause of Break"

"Blame Mulholland for Dam Structure"As the weeks passed and the list of missing dwindled, the ranks of the dead increased and the tally of property losses swelled, the search for the cause of the disaster — and the assigning of blame — played out in the area newspapers.

Everything from sabotage by Owens Valley farmers, to earthquake, to the eventual finding that the dam was built on a foundation of "slippery rock," was put forth in print in the days following the disaster.

Eventually, blame for the dam's failure was laid at the feet of the dam's builder, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power's Mulholland.

He was reportedly devastated by the disaster, and photos of him at the scene of the calamity on the morning of the tragedy show a shocked Mulholland as he surveyed the damage.

A Los Angeles newspaper dated March 14, 1928, was sympathetic to Mulholland.

"Mulholland's Heart Torn by First Disaster," the headline declares. "Chief Engineer Mulholland was a pitiable figure as he appeared before the Water and Power Commission yesterday afternoon to make his report on the visit to the scene of the disaster. His figure was bowed, his face lined with worry and suffering. As he told the commissioners of his trip, his voice was broken.

"Every commissioner had the deepest sympathy for the man who had spent his life for the service of the people of Los Angeles, administered the water department from village days to present and made the Los Angeles of today possible by building the Aqueduct and furnishing a supply of water for a city of 2,000,000 persons. In all his career of handling great projects he is facing the first disaster to any of his achievements. For his Irish heart is kind, tender, sympathetic and the tragedy for the people in the canyon and the Santa Clara Valley is the tragedy of William Mulholland."

Years after Mulholland's death, geologists discovered that the dam had been built in the area of an ancient landslide, something unknown to Mulholland and the geologists and engineers of the time. However, that may or may not have contributed to the dam's failure.

To find the true cause of the disaster, it may be necessary to return to the very beginning — the building of the dam.* * *Construction of the "concrete gravity dam with an arch" began in 1924 and ended in 1926. The St. Francis was originally built to stand 185 feet tall; however, in an effort to increase the capacity of the reservoir, the dam's height was increased to a towering 205 feet. A wing dike, 588 feet long and nearly 15 feet high, along the western embankment, further added to the reservoir's capacity.

Life-long Santa Clarita Valley resident Bailey Haskell, now 91, worked on the dam as a young man. His job was to help transport gravel from the creekbed. He criticized the materials used in the construction.

"They didn't use washed gravel," he said. "They were using gravel directly from the creekbed that had clay in it. I could see these great chunks of clay going right into the dam."

J. David Rogers, whose list of credentials is extensive and includes certified professional geologist, certified engineering geologist, certified hydrogeologist and member of the American Institute of Professional Geologists, has conducted numerous engineering studies of the dam site over the last 20 years. He now thinks he knows what caused the failure.

In hisyet-to-be-published paper, "Man Made Disaster at an Old Landslide Dam Site: A Day in the Field with Thomas Dibblee and J. David Rogers, St. Francis Dam area, May 17, 1997," Rogers reports a laundry list of 13 design deficiencies. Many of the failings are couched in technical and engineering terms: "Lack of hydraulic uplift theory being incorporated into the dam's design; lack of uplift relief wells on the sloping abutment sections of the dam; failure to batter the upstream face of the dam to reduce tensile forces via cantilever action; failure to analyze arch stresses of the main dam; failure to remove high water content cement paste (laitence layer) between concrete lifts; failure to account for the mass concreteheat-of-hydration ; failure to recognize tendency of the Vasquez formation to slake upon submersion and failure to provide the dam with grouted contraction joints."

However, other items on Rogers' list are more easily understood by the layman, including: "Failing to recognize that the dam concrete would eventually become saturated; failure to wash concrete aggregate before incorporation in the dam's concrete; failure to recognize the paleomegalandslide structure of the Pelona Schist comprising the dam's left abutment (the site of the ancient landslide); and failure to adequately account for changes in cantilever and arch loads caused by raising the dam 11 percent of its original design height (from 185 to 205 feet)."

His report states that despite the design deficiencies, the dam might have endured.

"Given the fact that so many other dams of that era were also built without a proper appreciation of uplift, and that more than 115 dams have now been identified as having been unknowingly built against paleolandslides, these factors, in themselves, cannot strictly account for the dam's untimely demise."

The report concludes, "Probably the greatest single factor that could be pointed to was the decision to heighten the dam a second time. Aside from the geologic shortcomings, all of the structural analyses predicted overstressed conditions when the reservoir pool rose within seven to 10 feet of crest. Had the dam not been heightened that last 10 feet, it might have survived."

What may have signaled the death knell for the dam was the final heightening that created an unstable structure. As the reservoir filled to the brim, just six days before the collapse, the massive force of the water behind the dam caused it to lift from its foundation, twist and crumble.* * *The official death toll of the St. Francis stands at 495. The true toll is probably higher when undocumented farm laborers are added to the rolls of the dead. No one knows exactly how many perished at their camps in the fields along the floodpath. It is known that more than 60 inhabitants of Power House No. 2, located 7,300 feet downstream from the dam, were killed when the

110-foot-high wall of water wiped the power house, and the family living quarters, from the face of the earth.

At a Southern California Edison construction camp located along state Route 126 at the LosAngeles-Ventura county line, 84 of the 150 workers encamped there perished. The power of the flood is hard to comprehend, but after traveling more than 50 miles down the Santa Clara River Valley, an AT&T lineman reported the wall of water was still 15 feet deep andthree-quarters of a mile wide when it reached the ocean at Ventura.

Lost in the mists of time is an exact accounting of the monetary cost of the disaster. Charles Outland, in hisout-of-print book, "Man-Made Disaster," tallies losses in excess of $13 million — in 1928 dollars.

The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society will hold a St. Francis Dam disaster talk and tour today starting at 1 p.m. at the Saugus Train Station in William S. Hart Park in Newhall. Society member Frank Rock will conduct a lecture and lead a bus tour to the dam site. The lecture is free; the tour is $25 per person.Keith Buttelman of Canyon Country contributed to this story.

©2001, THE SIGNAL · USED BY PERMISSION · ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.