|

|

Rewriting the West: Wyatt Earp and William S. Hart.

By Alan Pollack, M.D. | Heritage Junction Dispatch, Nov.-Dec. 2010

Graying frontier lawman calls on Hollywood luminary to shape his post-mortem legend.

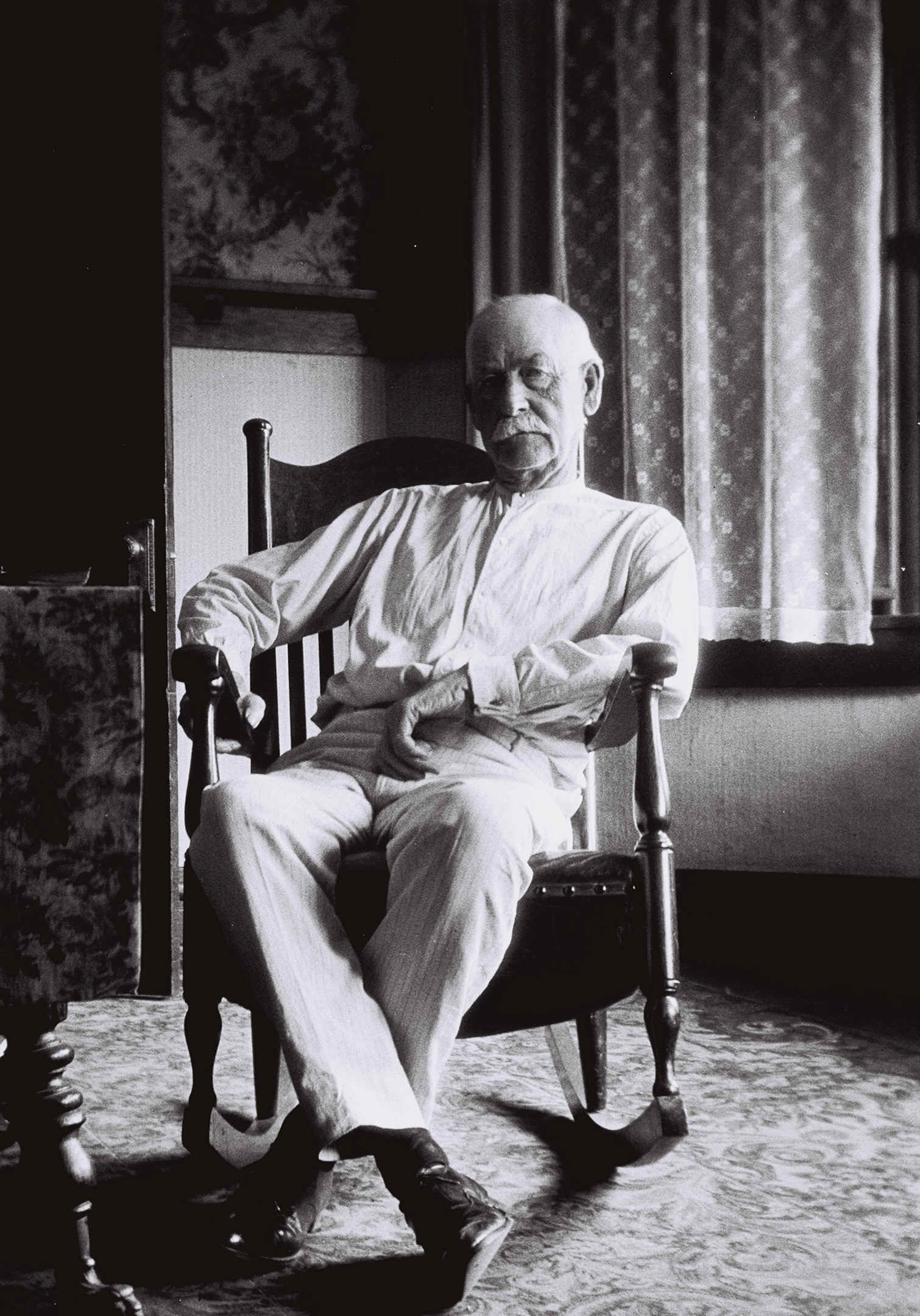

Aug. 9, 1923: Wyatt Earp, 75, at home in Los AngelesHe was best known for his exploits in Dodge City and Tombstone, including the most famous gunfight in the history of the West. But Old West lawman Wyatt Earp spent his last years in the Los Angeles area, and had a close friendship with the most famous citizen of Newhall.

It was late afternoon on the streets of Tombstone, Ariz. Tensions had been building for some time between the Earp brothers and a group of cowboys — a local term for cattle dealers or rustlers — from the Clanton and McLaury families. U.S. Deputy Marshal Virgil Earp requested assistance from his brothers Wyatt and Morgan and their friend Doc Holliday to confront the cowboys who were suspected of illegally carrying weapons in town. (At the time, carrying weapons was illegal within certain parts of Tombstone.)

The two factions had been spoiling for a fight. Today, Oct. 26, 1881, they were destined to have it.

The Earps and Holliday marched down Fremont Street and came to an alley one block from the entrance to the O.K. Corral, between Fly's Boarding House and the MacDonald House. There they confronted Ike and Billy Clanton, Frank and Tom McLaury, and Billy Claiborne.

About 30 shots rang out in 30 seconds. Three men — both of the McLaurys and Billy Clanton — were left dead.

The legend of Wyatt Earp was born that day when he escaped without injury from a shootout that would come to be known as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, a popular subject of later books and movies.

Early Days

Wyatt Earp first came to California on a wagon train with his family in 1864. He subsequently found work in the Imperial Valley as a driver for Phineas Banning's stagecoach line. He also worked as a teamster on routes between Wilmington, Calif., and Prescott, Ariz., and between San Bernardino and Salt Lake City.

By the 1870s Earp had moved on to Kansas, where he got his first job as a lawman in 1875 in the cow town of Wichita. His career as an officer in Wichita ended the next year when he got into a fistfight with a former marshal who questioned his motives during the election for city marshal.

Earp lost his job and moved on to the next cow town, Dodge City, where he served stints as assistant city marshal in 1876 and 1878.

He first met gambler and dentist Doc Holliday at Fort Griffin, Tex., in 1877. Holliday followed Earp back to Dodge City the next year and saved his life when a cowboy drew a gun on Earp as Earp attempted to break up a barroom brawl. Earp and Holliday would become lifelong friends.

Tombstone

In December 1879, Earp moved to Tombstone with his brothers Jim and Virgil. Virgil had been appointed a deputy U.S. marshal, while Wyatt took employment with Wells, Fargo & Co., riding shotgun for its stagecoach lines. He also served for a short time as a deputy sheriff in Pima County.

Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday arrived in Tombstone in the summer of 1880. After the famous gunfight in Tombstone, the Earps and Holliday faced murder charges, which were subsequently dismissed.

Virgil Earp lost the use of his left arm after being shot on Allen Street in Tombstone in December 1881. Ike Clanton was suspected of shooting Virgil but was later acquitted.

A few months later in March 1882, Morgan Earp was gunned down and killed in a Tombstone pool hall. Wyatt Earp spent the next three weeks leading a federal posse to avenge the killing of his brother. In what became known as the Earp Vendetta Ride, four men suspected of involvement in Morgan's assassination were killed by the Earp posse.

The Earps next headed for Colorado, settling for a short time outside of Gunnison. They split up with Holliday, who moved on to Pueblo and Denver. Later in 1882, Wyatt and Virgil ended up in San Francisco, where Wyatt rekindled a romance with Josie Marcus, the woman with whom he would spend the remaining 46 years of his life.

Over the next two decades, Wyatt and Josie roamed the West, making stops along the way in Gunnison (where Earp ran a faro bank), Dodge City, various boom towns in Colorado, Idaho, and Washington; and San Diego and San Francisco. The lure of gold brought Earp to Nome, Alaska in 1897, where he ran saloons and gambling halls for a few years.

Wyatt Earp and William S. Hart

Earp and Josie returned to California in 1906. They eventually moved to Hollywood, where Earp served as a consultant on movie sets. There he met several famous actors including silent Western film star William S. Hart.

Earp had become increasingly frustrated with the inaccuracies and untruths about his life as portrayed in the media. He began a correspondence with Hart in 1920, inquiring about making a movie with a more realistic depiction of his life and career in the West.

Earp wrote in 1923: "During the past few years, many wrong impressions of the early days of Tombstone and myself have been created by writers who are not informed correctly, and this has caused me a concern which I feel deeply. ... I realize that I am not going to live to the age of Methuselah, and any wrong impression I want made right before I go away. The screen could do all this, I know, with yourself as the master mind."

The correspondence developed into a close friendship between the two men. Earp and Hart continued a frequent correspondence in the ensuing years, until Earp's death in 1929.

During these years, Hart attempted to help the now elderly Earp get his true story told. Earp again wrote to Hart in 1925: "I wonder whether you still would be inclined to film the production. If it goes on the screen at all, I would not want anyone but you to play the role and to put it there. ... I am sure that if the story were exploited on the screen by you, it would do much toward setting me right before a public which has always been fed ... lies about me."

Hart and the Biography of Wyatt Earp

Hart never did a film production on the life of Wyatt Earp, but he did continue to help Earp in his quest to find an author to write his life story.

Earp approached Hart again in 1926 about a manuscript on his life, written by Earp's personal secretary John H. Flood. Hart sent the manuscript to the Saturday Evening Post for possible serialization but received a rejection which stated that the book had "a trifle too much gunplay in it for the average reader. ... There is too much straining for effect. ... We are reluctantly declining the book."

In January 1928, Earp was approached by San Diego author Stuart N. Lake, who expressed interest in writing his story. Earp asked for Hart's advice about Lake, but Hart replied that he had never heard of him. After a personal visit with Lake in June 1928, Earp agreed to allow Lake to write his biography. After Earp's death the following year, Hart approached Houghton Mifflin to help Lake get the biography published. Over the next two years, Hart and Lake struggled with Earp's widow, Josephine, who repeatedly demanded revisions to the book.

Further Reading

Wyatt Earp's Letters to Bill HartLake would write to Hart: "Her interest is not historical accuracy; she wishes to make sure that I tell what she calls Ďa nice clean story.' ... I have tried to explain to Mrs. Earp that the saloons were merely incidental spots in the landscape, gambling was in the relationship of latter-day golf, but God knows I lack the temerity to try to gloss over the shooting."

Finally in late 1931, Lake successfully published "Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal." Still considered one of the definitive books on Earp, Lake's tome unfortunately suffered somewhat in accuracy due to the demands Josephine Earp placed upon him.

Frontier legend Wyatt Earp died at age 80 in Los Angeles on Jan. 13, 1929. Actors William S. Hart and Tom Mix served as pallbearers at the funeral. Earp's ashes were buried in the plot of his wife's family at the Hills of Eternity Cemetery in Colma, Calif.

Upon his return to Newhall, William S. Hart wrote: "I have just returned from the funeral services of a very dear friend of mine, who has crossed the Big Divide — Wyatt Earp, the last of the really great gunmen-peace officers of the frontier."

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.