|

|

Great Flood of 1938: Skies Open Up with Deadly Force.

Heritage Junction Dispatch | July-August 2019.

|

We certainly had a wet winter this year. But it pales in comparison to a 50-year flood that pummeled Los Angeles and the Santa Clarita Valley in February-March of 1938. The damage from this epic storm led to the construction of the many flood control channels which we are familiar with today. The Five-Day Deluge. It all started February 27, 1938, when 1.42 inches of rain fell on the Los Angeles area. The Los Angeles Times reported: "The rain is only a forerunner of additional storms heading southeastward from the North Pacific." Another 2.25 inches of rain flooded the area the next day. Heavy runoff "brought debris-laden currents surging to doorsteps of many homes and stalled automobiles by the thousands on low-lying streets and highways." The Los Angeles area then received a 15-hour reprieve from the storm, only to be followed by another storm that hit the area on the evening of March 1. The new storm spread from Los Angeles to Burbank, Glendale, Beverly Hills, Sandberg, Saugus and Santa Monica. Many streets were said to be choked with debris with occasional broken or sunken pavement. One man died of a heart attack when he tried to extract his car from a mud-covered road in Colton. Police had warned him not to drive over the road to no avail. Venice was particularly hard hit as it received much of the drainage from areas of higher elevation. Residents were reported to be splashing along in streets that had become canals and several homes were flooded. The Los Angeles River overflowed its banks in downtown Los Angeles and carried away 30,000 board feet of lumber intended to be used to construct a Union Pacific bridge to the new Union Passenger Terminal. Residents in Topanga Canyon were isolated by numerous mud slides in the canyon.

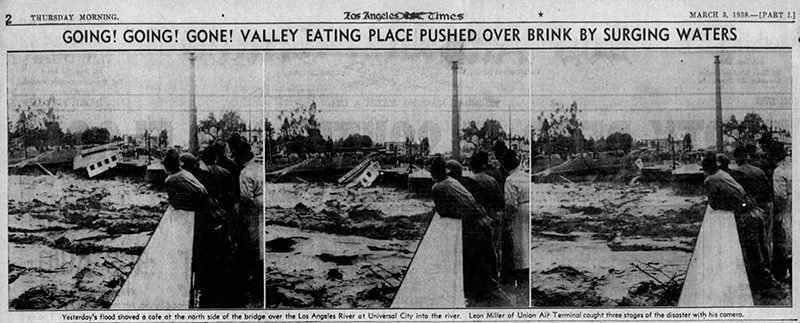

But the deluge wouldn't stop. The Los Angeles Times headline March 3 declared: "Thirty Dead in Southland Floods." Southern California's heaviest rainstorm in a quarter-century had entered its fifth day. Bridges in Long Beach and Universal City collapsed, sending 15 people to their deaths in the flood waters. The Times reported: "Property damage ran into the millions as bridges broke, highways sank, homes collapsed, commercial houses swam, and gardens and ranches were flooded." A pedestrian bridge in Long Beach collapsed, resulting in up to 12 people drowning in the Los Angeles River. Five people died when the 250-foot Lankershim Boulevard bridge collapsed into the Los Angeles River at Universal City. The dead included a 26-year-old woman along with her 1½-year-old son who were buried when a landslide hit their home in Beverly Glen. Her husband survived and was found in his bathtub several hundred yards down the canyon. In all, 6.29 destructive inches of rain fell on Los Angeles that day. Thousands of families had to be evacuated from their flooded homes in the San Fernando Valley, Compton and Venice. Los Angeles became isolated as three transcontinental railroads had to stop service due to bridge washouts and flooded lines. The Pacific Electric Railway service was crippled by the floods. Landslides in the Santa Monica Mountains killed at least six people. Scores of people were injured when their homes were crushed like match boxes when tons of rock and earth fell on them. More flooding occurred in the San Fernando Valley when the flood gates of the Big Tujunga Dam had to be opened to save the structure from collapsing. Van Nuys became isolated when all major bridges into the area were flooded or washed away. Homeowners had to be rescued from their flooded homes by a flotilla of boats. Even movie stars such as Leo Carrillo and Dolores Del Rio were evacuated from their homes. A broken levee on the Los Angeles River sent hundreds of residents between Glendale and Los Feliz Boulevards fleeing to higher ground. By the next day, the death toll had risen to 62. In all, a total of 11.06 inches of rain fell on the city during the five-day storm. Los Angeles was said to be a "lonesome metropolis," unable to communicate with the rest of the world by means of rail, bus, airplane, telephone or telegraph. Fifteen hundred homes were declared uninhabitable, resulting in 3,700 storm refugees. Due to a break in the main Hoover Dam power line, much of the city was without electricity. In addition, there were shortages of gas and ironically water. Yet, things could have been worse. The city's $50 million investment in a vast flood control system of dams was credited with the prevention of tremendous loss of property and life. However, there was extensive damage to roads and bridges throughout Southern California, requiring a massive repair effort. Damage in the Santa Clarita Valley.

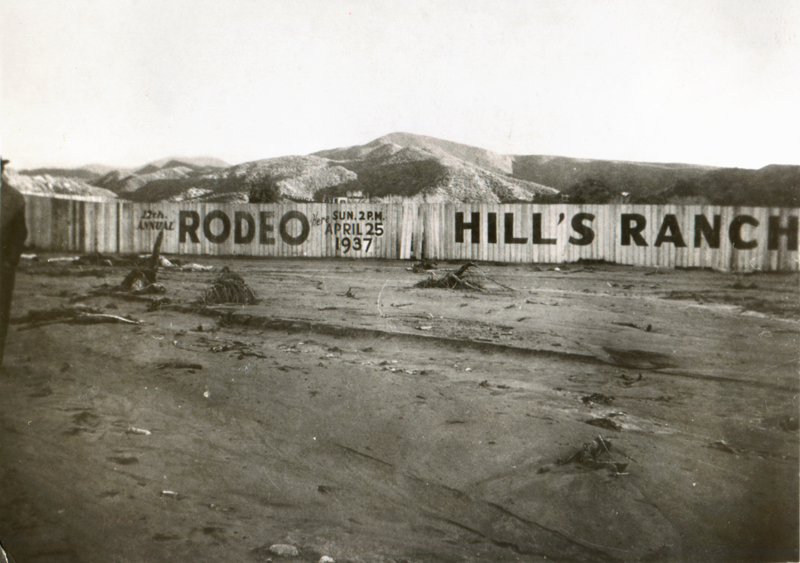

Also falling victim to the great flood of 1938 was the Santa Clarita Valley. Roads were damaged all across the valley as water roared down from the surrounding canyons. The tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad suffered extensive damage. Several bridges were out in the Saugus area, as well as the Pico Bridge west of Newhall. Multiple cave ins occurred in the Newhall Auto Tunnel causing several closures to auto traffic. The entire valley was illuminated by a fire occurring at the Edison Saugus substation when a gas main broke. Much of the town of Castaic was reported to be flooded. A major traffic artery through the valley was blocked when the bridge over Castaic Creek was washed out just west of Castaic Junction. The home of the James Fryer family was washed away by the flood waters of the Santa Clara River in Soledad Canyon. The school at Honby lost all of its outbuildings. Two big bridges on Soledad Canyon road were washed out. Most of the buildings at the Nadeau Deer Farm in today's Canyon Country were destroyed. The flood severely damaged the grounds of the Saugus Rodeo in Soledad Canyon. Shortly thereafter, Paul Hill, owner of the rodeo at that time, lost the property to bank repossession. Ownership passed to William Bonelli in 1939. He eventually transformed the rodeo arena into the Saugus Speedway. Aftermath. Approximately 115 people perished in the floods of 1938 in Los Angeles. Damage was estimated at $78 million. 5,600 homes and businesses were lost in the floods. Afterward, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers channelized many of the local streams in concrete, thus creating the flood control channels that we see throughout Los Angeles today. Sources for this article: Los Angeles Times, February 28 - March 5, 1938; Newhall Signal, March 3, 1938. Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.

Download individual pages here.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.