|

|

REVOLT OF THE BALKANS

The Move to Secede from Los Angeles County.

By Bob Simmons.

California Journal | April 1976.

|

Webmaster's note.

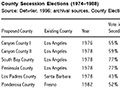

In a scathing rebuke of the mutinous Santa Clarita Valley residents who twice voted to break away from Los Angeles County (in 1976 and 1978), CBS affiliate KNXT-TV reporter Bob Simmons quotes county officials saying they could afford to lose us, but our new "Canyon County" would run in the red. The story ran in the April 1976 edition of a state government journal. By election day (Nov. 2), the county was making the opposite claim. County employees, particularly the firefighters union, spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to convince Angelenos they couldn't afford to lose the tax dollars that the SCV was overpaying the county for municipal services. SCV residents approved secession by a 55-45 percent vote in 1976 and an even greater margin (59-41) in 1978, but secession required the consent of the county being vacated. The rest of the county voted to keep us — by 68-32 percent in 1976 and 64-36 percent in 1978. After that, the Legislature changed the rules: Any new county must have a minimum population of 5 percent of the mother county. At the time, we were at 1 percent. (Forty years later, in 2017, the SCV is still only 3 percent — 300,000 of 10 million.) A decade after Canyon County, many of the same rebels would regroup and form a new city.

"For most of our citizens, local government is the first test by which our civilization is judged."

— Public Commission on County Government, Los Angeles, February 1976 In the rough and folksy bars of Saugus they argue about the new county. Between rounds of beer and eight ball, lean men in faded Levi's wonder if their taxes will go up, if fire and flood protection will go down. A few miles away, in the Sunset Magazine living rooms of Valencia, the questions are different but the issue is the same. Members of the League of Women Voters ponder the ethics of pulling a white, middle-class suburb out of a county which last year provided welfare assistance to 742,000 people and needs all the resources it can gather. The Canyon County Formation Committee wants to separate 66,000 people and 735 square miles from Los Angeles County. The northwest corner of the existing county would break off to become Canyon County, which would include the unincorporated communities of Saugus, Newhall, Valencia, Canyon Country, Acton and Gorman, plus thousands of acres of sparsely settled range- and prime-development land along the Santa Clara River. That corner of Los Angeles County is connected with the county seat by 50 miles of freeway and is separated by row on row of mountains and canyons, and years of mutual disinterest. "People downtown don't know where the Santa Clarita Valley is," says Don Hon, Newhall attorney and co-chairman of the Canyon County drive. "People in this valley don't give a damn what goes on downtown. Why should we be tied together? We're sick and tired of driving a hundred miles round trip to attend a Planning Commission hearing, to appeal an assessment or complete a building permit."

The budget blues

Los Angeles County's chief administrative officer, Harry Hufford, thinks Los Angeles County can get along without its northwest corner, but he doesn't see how the proposed new county can make it on its own. Canyon County would reduce L.A. County by only about one percent of its population and one percent of its tax base. Hufford says L.A. County expenditures would decrease by $23 million, but the new county's budget, he estimates, would have to exceed $33 million. "That's ridiculous," scoffs Hon. "He's assuming we would continue the same wasteful, inefficient, overspending ways L.A. County's famous for. They always buy a Cadillac when a Volkswagen will do." Until two years ago this would have been idle chatter. There had not been a new county formed since Imperial County in 1907. The barriers to secession were enormous. But new legislation in 1974 made new county formation much easier. When 25 percent of the voters in the proposed county have signed petitions to separate from their existing county, the formation is underway. The voters of the existing county can block it, but the supervisors cannot. The petition phase happened rapidly in northwest Los Angeles County, and similar actions are now threatened in the eastern, southern and western reaches of the county to split off more densely populated, higher-priced chunks. The Canyon County signatures have been certified and sent to Governor Brown. Now the Governor must appoint a County Formation Review Commission — two residents from the proposed new county, two from the remainder of Los Angeles County and one from another county. The commission would decide who would owe how much to whom for county property that would have to be exchanged. It would estimate the financial impact of the separation on the old as well as the new county and officially certify the boundaries. Once that's done the Los Angeles County Supervisors must call an election to decide the fate of the new county. If the separation is approved by a majority in the overall existing county as well as in the proposed new one, 91 days later Canyon will become California's 59th county. Canyon forces have been waiting impatiently for word from the Governor. He has until May 1 to appoint the commission and there has been no indication he will do it before that deadline.

South Bay, San Gabriel and Las Virgenes

Meanwhile, separation petitions are circulating m Torrance and the beach cities of El Segundo, Redondo Beach, Manhattan Beach, Hermosa Beach, Rolling Hills and Palos Verdes for a new entity to be called South Bay County. It would take about six percent of the population and six percent of the tax base from Los Angeles County. A committee of San Gabriel Valley officials headed by Mayor Louis Gilbertson of Temple City is pondering the potential of a new County of San Gabriel. The loss of its 27 cities would remove about 13 percent of the existing Los Angeles County tax base. Dissidents in the western end of Los Angeles County keep raising the possibility of a Las Virgenes County. One version would include the beach community of Malibu, the Santa Monica Mountain country to the north, the Ventura Freeway communities of Agoura and Calabasas, and the burgeoning Ventura County suburb of Thousand Oaks. (Plans are also afoot to create city-county governments in central Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley.) Whatever the outcome, there's a certain irony in the threatened balkanization of Los Angeles County. For years the county Regional Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors have approved subdivisions virtually on demand, even when bitterly opposed by those constituents who already had made the move to suburbia. Now, of the seven million who live in Los Angeles County, only a bit more than two million live in the City of Los Angeles. The rest are spread along the freeways to the outer fringes, and the outermost are turning against the county, demanding to be let out. "The county is a monster," roars the Newhall Signal, "that nourishes itself on the life blood of the people of the Santa Clarita Valley."

Too many Newhalls?

A lot of things about the proposed new county would be named Newhall — too many to suit some opponents of the plan. Scott Newhall, former editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, is publisher — his wife, Ruth, is editor — of the Newhall Signal, published in the town of Newhall. The Newhall Land and Farming Company would be the largest taxpayer in the county. It owns hundreds of acres of flat land in the Santa Clara flood plain. Supervisor Baxter Ward does not mention the Newhalls by name but makes it clear whom he's talking about when he warns, "The interests are, I think, interests that want control of zoning or development, that kind of thing ... and they are utilizing the people's concerns about the tax dollars as a means of gaining the control they selfishly seek." On the other hand, secession leaders claim the existing Regional Planning Commission has done such a terrible job of shaping the Santa Clarita Valley that the development pattern is a major factor in the residents' determination to get out. They'll show you the hilltop subdivision in high-hazard fire and earthquake country, with only one narrow street in and out to be shared by rescue equipment and fleeing residents in the event of disaster. Bouquet Canyon Road stretches out into a straight, 55-mile-an-hour highway, suddenly takes a 25 mile-an-hour bend for no apparent reason, then returns to its former alignment. The county road department says it was put there according to a community plan provided by the county planning department. Discussion during a recent planning commission meeting revealed something of the insularity in which land-use decisions are made. Residents from the proposed Canyon County area had driven 50 miles to argue for and against a proposed new subdivision, only to have the commission postpone the hearing. Commissioner Carolyn Lewellyn, (the only one of the five with no connections in real estate, land development or the escrow business) worried about inconveniencing those who had driven all that way. She suggested that when the public arguments were rescheduled, they be heard in the community itself, for the convenience of those affected. Commission Chairman Howard Martin was dead set against it. "It doesn't make sense," he said, " to drive all the way to the Santa Clarita Valley when it's so much easier to meet right here."

The commission report

While the rebels of Canyon, San Gabriel, South Bay and Las Virgenes look for a way out, a prestigious Public Commission on County Government has spent a year looking for a way to bring everybody in. "Public knowledge of and confidence in county government are low," warns the commission's final report. "Its remoteness and low visibility are important elements underlying the four major movements now working to secede from the county. Citizens participate very little in decision-making, and the structure is not built to respond when citizen opinion is formed and presented." While there are more than 100 advisory boards, commissions and committees to counsel Los Angeles County officials, those who serve on the panels often find they're wanted only as window dressing — meeting the requirements for state and federal grants but having no access to the decision-making process. One such group was appointed to develop affirmative action plans to aid the county in hiring and promoting more minorities and women. "It spent two years producing a report and then watched it filed and forgotten," the Public Commission says, "without even the courtesy of an explanation of the reasons for which it was being ignored." A Citizen's Advisory Planning Council tried to warn the Planning Director, Planning Commission and Supervisors that the general land-use plan they were developing in 1973 was illegal. But council members were totally cut off from all the officials involved. Last July, a Superior Court judge threw out the general plan and told the county to start over. The Public Commission believes these and other frailties of the existing county government are the product of faulty structure. It proposes an elected county mayor to take over management of the fifty-plus county departments, an expanded board of supervisors to be known as the County Legislature, an independent auditor-controller appointed for a 10-year term, and other innovations. While the Canyon separationists complain of being alienated from Los Angeles, those of San Gabriel concentrate their fire on the cost and inefficiency of the existing county government. Mayor Gilbertson points to the Los Angeles County general tax rate — the highest of any California county in 1975 — as reason enough to try something smaller. He refers to a University of Southern California study which indicate s that services don 't get any cheaper as government gets bigger. (The 1970 study of metropolitan governments concludes that the cost per capita never levels off once you pass a governmental unit size of 100,000.) Los Angeles County's experience seems to support the finding. In the past 25 years, the county's population has grown less than 70 percent, but the number of employees has increased by more than 200 percent (now numbering more than 84,000, about the size of the city of Burbank). And the annual cost of running the county has gone up more than 900 per cent, with total expenditures in 1975 of more than $3 billion. CAO Hufford warns, however, that if the smaller counties try to do the things Los Angeles County does for its citizens, the cost will be exorbitant. His analysis of the proposed Canyon County predicts that "in order for the new county to continue to provide services at the level now provided, a real property tax of $8.95 per $100 ... would have to be levied, compared to the 1974-75 Los Angeles County tax rate of $4.68."

Where are the buildings?

"So we'll do without a few things," he says. "Maybe we'll get by without a $14 million crime computer that doesn't work (a reference to L.A. County's ill- fated Oracle project). Maybe we won't need a whole big department to find out where the county buildings are." (Los Angeles County's Facilities Department is just concluding the first-ever inventory of approximately 4,000 county-owned structures.) County officials are quick to point out that a great deal of the 900 percent increase in expenditures since 1950 has gone for social welfare programs mandated by the state and federal governments. And some believe the separationists are trying to escape helping the poor, elderly and disabled of the urban center. The percentage of public assistance recipients in either Canyon County or South Bay County would be considerably smaller than the percentage in the existing county, where one out of eight residents is either on relief or on the county payroll (742,000 on welfare plus 84,000 county employees). But Connie Worden, co-chairperson of the Canyon County Formation Committee, says the move is not a continuation of the "white flight" to shed social responsibility. "If I thought we were hurting Los Angeles County's ability to deal with its social problems I'd drop the project right now. I don't think the loss of our little corner is going to affect the rest of the county one way or another. I do think that enough breaking away could leave behind a ghetto county, and we would not want to be responsible for doing that."

The outlook

Temple City's Mayor Gilbertson points out that the proposed San Gabriel County would have its share of Blacks and Spanish-speaking poor. "You just can 't run away from the need to care for the disadvantaged," he says. "For one thing, the rest of the county would not allow it. If they did, it 'd be the wrong thing to do." Nevertheless the rash of county formation campaigns raises the spectre of an under-financed, overburdened Los Angele s Count y, struggling to handle its social pressures with a drastically reduced tax base. That prospect, coupled with the job concerns of militant county employees, would seem to diminish the new counties' chances of getting the majorities they need. But Connie Worden thinks Canyon County has a good chance, partly because of its remoteness. "I felt we'd won," she said, "when the clerk at the Registrar of Voters' office looked over our petitions and asked, 'Where in the heck is Saugus?'"

Bob Simmons (pronounced Simons) was a reporter for KNXT-TV. At the time, KNXT was the Los Angeles affiliate of CBS Inc., formerly known as the Columbia Broadcasting System.

LW3104: pdf of original program book purchased 2017 by Leon Worden. Download individual pages here.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.