|

|

Click image to enlarge

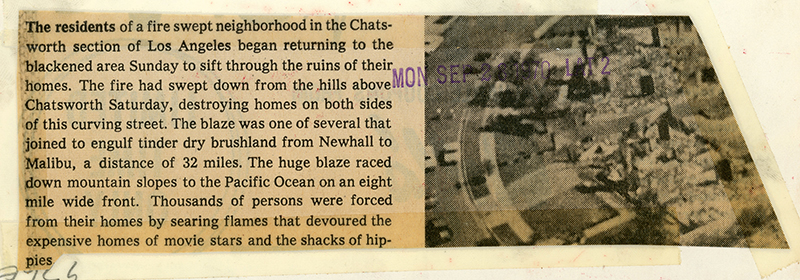

A Chatsworth neighborhood is destroyed in the Clampitt Fire, which started Sept. 25, 1970, in Newhall and burned through to the sea where it merged with another fire. 7x11-inch wire photo date-stamped Sept. 28, 1970, from an unknown newspaper archive, possibly Los Angeles Times. Cutline reads:

The residents of a fire swept neighborhood in the Chatsworth section of Los Angeles began returning to the blackened area on Sunday [Sept. 27, 1970] to sift through the ruins of their homes. The fire had swept down from the hills above Chatsworth Saturday, destroying homes on both sides of this curving street. The blaze was one of several that joined to engulf tinder dry brushland from Newhall to Malibu, a distance of 32 miles. The huge blaze raced down mountain slopes to the Pacific Ocean on an eight mile wide front. Thousands of persons were forced from their homes by searing flames that devoured the expensive homes of movie stars and the shacks of hippies.

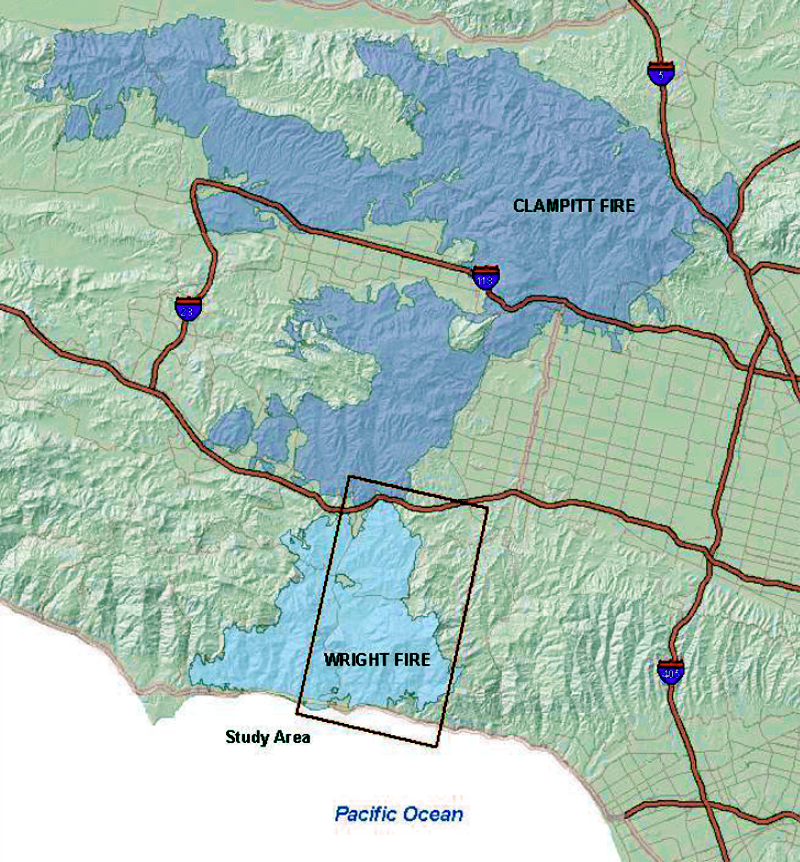

The Clampitt (Newhall) and Wright (Malibu) fires of Sept. 25, 1970, merged to become the largest and deadliest wildfire in modern Los Angeles County history, up to that point. The Clampitt fire broke out around 8 a.m. Friday, Sept. 25, near Clampitt Road in the Newhall Pass as a result of downed power lines. In Santa Ana winds clocked at 80 mph, it took less than a day for the fire to make a 20-mile run to the coast, tearing through Porter Ranch, the Simi Hills at Chatsworth, south to the 101 Freeway and on to Malibu Canyon. News reports initially called it the Chatsworth-Malibu Canyon fire because much of the destruction occurred there.

By the time the smoke cleared, the Clampitt Fire had scorched 107,103 acres of brush and forest, destroyed 80 structures killed four civilians (source: University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources). It still stands as L.A. County's deadliest wildfire in modern history and was the largest until 2009 when the Station Fire, which claimed the lives of two firemen, passed it in acreage. (Giant fires of indeterminate size in the San Gabriel Mountains in 1896 and 1919 may have been bigger; see Robinson 1977.) The Wright Fire was credited with charring an additional 27,925 acres and destroying 103 more homes (source: UCANR). Together with a simultaneous blaze in Agua Dulce, the three fires burned 157,058 acres. Locally, the Clampitt Fire encroached on the historic buildings of Mentryville in Pico Canyon where an inmate camp crew and a single fire engine were on hand to save the barns and corrals while the resident Lagasse family helped keep the flames away from Alex Mentry's 1890s mansion and various outbuildings. Most of the structures made similarly narrow escapes in August 1962 and October 2003 (the Wolcott barn was lost in the 1962 fire). Meanwhile in Chatsworth, the fire leveled the old movie-set buildings of the Spahn Ranch, where Charles Manson and his "family" had been living in 1968 and 1969. The next day, Sept. 26, downed power lines sparked another fire in San Diego County. Dubbed the Laguna Fire, it consumed 175,425 acres, killed eight civilians and destroyed 382 homes. All told, the California wildfires of September to November 1970 blackened more than 600,000 and came to be called the "1970 California Fire Siege." Less than five months after the Clampitt fire, the Sylmar-San Fernando earthquake rocked much of the same area, prompting locals to adopt the term "shake 'n bake" from a popular food coating of that name. Excerpt from paper by Thomas R. Forrest, Department of Sociology, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, titled "Structural Differentiation in Emergent Groups" (March 1974), published by the Disaster Research Center, Columbus, Ohio 43201: This document is one of a series of publications prepared by the staff of the Disaster Research Center, The Ohio State University, on sociological aspects of community emergencies. The research reported here was done as part of a comparative study of responses in civil disturbances as well as natural disasters... Abetted by drought, arsonists and fierce Santa Ana winds, the worst fire in Southern California's history broke out on Friday, September 25, 1970. The next ten days saw twelve separate fires destroy 525,000 acres of brushland (an area more than half the size of Rhode Island), leaving 13 killed, 350 injured and an estimated 1,500 buildings destroyed and damaged. Damage totaled $200 million. These figures include destruction of 400 houses, leaving 450 families homeless. Most of the damage was contained within four national forests: Cleveland National Forest, San Bernardino National Forest, Angeles National Park and Los Padres National Forest. There were three major reasons this fire started, reasons that are inherent in Southern California life. First, the rolling hills of Southern California are covered with a dense brush called chaparral, a scrub ever- green. Chaparral was the fire's source of fuel, causing a heat energy out- put of 2,500 Hiroshimas. Second, the affected area is virtually a desert. At the time of the blaze it had not rained in almost 200 days (since March 4). This, coupled with a daytime humidity of 5 to 10 percent and tempera- tures of 100?F, made the dense chaparral extremely dry and subject to immediate explosion. Finally, the massive brush fires that erupted were aggravated by a dry, northeast wind from the Mohave Desert called the Santa Ana or "devil" winds. With gusts at times reaching 100 miles per hour, these winds not only contributed to the dry, arid conditions that precipitated the fire but were also the major factor preventing fire- fighters from early control of the blazes. In addition to the climatic conditions there were a number of reported instances of arson. Arson is believed to be the cause of the San Bernardino blaze and perhaps five other minor fires. The first ignition of the California fires began about 10:30 a.m. on Friday, September 25. Two major fires, in Malibu and Newhall, erupted about 25-30 miles from downtown Los Angeles along the Pacific Ocean. The Malibu fire started at a public dump, where embers from burning rubbish spread to the surrounding brush. Spreading across 50 acres in five minutes these flames moved toward the sea. Another fire broke out to the north near Newhall, in the dry foothills of the Santa Susana Mountains. Mean- while, a third and fourth blaze were starting in Ventura County. These four fires combined to create a massive fire wall that extended for 30 miles north of Los Angeles. An army of firefighters, aided by some 2,000 convicts, fought this combined blaze. This was one of the worst of all the Southern California fires, extending from the Pacific Ocean at Malibu to the Los Angeles National Forest near Newhall and burning approximately 120,000 acres of brushland. Another fire began to the south in Cleveland National Forest, 50 miles east of San Diego, when sparks from a power line spread to the brush. The blaze quickly moved westward to El Cajon and Spring Valley. As of Monday, September 28, the firefighters had stopped the westward progress of the fire, but it proceeded southward instead, burning 185,000 acres and destroying about 250 homes. In addition, between 50,000-60,000 people were forced to evacuate the outskirts of San Diego. As the fire took its toll, federal, state and local agencies and organizations began to mobilize their resources to provide relief and assistance. Teams of federal and state assessors swarmed into the stricken a rea. The Off ice of Emergence Preparedness announced that federal funds would be available to supplement state and local resources. This assistance took the form of long-term, low-interest loans for those who lost homes, businesses and farms; removal of debris at federal expense; special unemployment compensation for those displaced from their jobs because of the fire; use of money from the President's disaster fund for the repair or replacement of public property affected by the fire; and repair of flood control structures and cleaning of flood channels. Also the state Division of Forestry announded that a million pounds of seed would be made available for re-seeding burned lands. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors passed an emergency ordinance permitting persons whose homes had been destroyed to move trailers onto their property while they were rebuilding. Countless other agencies, organizations and volunteer associations assisted in restoration activities. While formally established organizations lent their assistance, individual citizens assisted their friends and neighbors in providing shelter, food, clothing, debris clearance, financial assistance and numerous other necessities. In many instances, this assistance blossomed into a fairly sophisticated organized group effort which persisted over several days and weeks.

LW2884: 9600 dpi jpeg from original photograph purchased 2017 by Leon Worden.

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.