|

|

Final PEIR (Programmatic E.I.R.): Cultural Resources

|

North Los Angeles / Kern County Recycled Water Project Final PEIR (Programmatic Environmental Impact Report) Cultural Resources Section | 2008

Note: The entire Cultural Resources section appears in .pdf form above. Only an excerpt appears in text form below, including a discussion of the paleontology, (Tataviam and Kitanemuk) prehistory, and history of the project area. For a listing of previously recorded archaeological sites and certain other information, see the .pdf above.

3.4.1 Setting ArchaeoPaleo Resource Management, Inc. (APRMI) archaeologists Shannon L. Loftus and Robin D. Turner performed the Phase I Cultural Resource and Paleontologic Assessment (Phase I Assessment) of the proposed project APE. The results of the study are documented in a confidential archaeological technical report titled Cultural Resource and Paleontologic Assessment: North Los Angeles/Kern County Regional Recycled Water Master Plan, Los Angeles/East Kern Counties, California. This technical report serves as the primary reference source for the following summary discussion of the archaeological and paleontologic investigation of the proposed project. Prehistoric Context General scholarship notes the prehistoric occupation of southern California by various hunter-gatherer groups to at least 12,000 years before present (B.P.) (Moratto, 1984). Specifically, the Antelope Valley foothill region has been identified as an axis between coastal and desert populations, as well as northern populations of the Eastern Sierra and northern California (Loftus and Turner, 2008). Prehistoric human subsistence is believed to have involved the seasonal exploitation of natural resources by small groups, a strategy that was successfully employed until approximately 2,000 B.P. After that time changes in the cultural adaptations of these prehistoric communities occurred, changes believed to have been caused by an increase in population, among other potential catalysts. Other potential catalysts for this change include changes in the environment, social organization, technology, or perhaps a combination of all. Specific changes that have been identified include a shift towards more sedentary settlement pattern with the appearance of semi-permanent villages and an increase in small campsites associated with these larger villages (Loftus and Turner, 2008). Loftus and Turner (2008) identify a generally accepted chronology for dating the various cultural phases of the prehistoric populations that occupied the Mojave Desert and the Great Basin area, which can likewise be applied to the Antelope Valley. This chronology proposes seven specific cultural phases: Pre-projectile Point Period (20000 — 10000 B.P.), Paleo-Indian Period (ca. 10000 B.C. — 8000 B.C.), Lake Mojave Period (8000 B.C. - 5000 B.C.), Pinto Period (5000 B.C. — 2000 B.C.), Gypsum Period (2000 B.C. — A.D. 500), Rose Spring Period (A.D. 500 — 1000), and the Late Prehistoric Period (A.D. 1000 to contact). The Pre-projectile Point Period is a contentious cultural phase that is proponed by some researchers to place early lithic traditions such as Calico, Lake China, and Lake Manix. Specific references can be found in the Loftus and Turner archaeological report (2008). The Paleo-Indian Period is the period associated with Big Game Hunting Traditions that utilized fluted points for hunting late Pleistocene megafauna. A few of these Paleo-Indian fluted points have been found in the Mojave Desert. Examples of Paleo-Indian fluted projectile points include the Clovis and Dalton point types. During the Lake Mojave Period, a diversification of artifact and ecofact assemblages occurs, suggesting the adoption of broader adaptation strategies by prehistoric populations. Artifacts associated with this period include the long-stemmed Lake Mojave and shorter-stemmed Silver Lake projectile points, finds which are often associated with terminal Pleistocene lake shore locations. Relatively few millingstone artifacts have been found in Lake Mojave Period contexts, suggesting a subsistence pattern that emphasized hunting. The following Pinto Period is characterized by generalized hunter-gatherer populations that occupied seasonal camps in small numbers; it is most likely that the earliest occupants of the project area can be placed within this period. Artifacts of this period are exemplified by the Pinto projectile point type, probably evidence of atlatl use, and the appearance of settlement sites near to ephemeral lakes and now-dry springs or creeks. There is a noticeable lack of groundstone or millingstone artifacts at Pinto Period archaeological sites. Cultural adaptations occurred during the Gypsum Period to more arid desert conditions, adaptations that resulted in an increased emphasis on socioeconomic ties through trade, the development of new technologies and more complex ritual activities. Artifacts commonly associated with the Pinto Period include a wide variety of projectile point types including, but not limited to, the Humboldt Concave base, Gypsum cave, and Elko Eared or Elko Corner-notched, as well as the first appearance of trade artifacts made of shell. A continuation of these artifacts extends into the next period, the Rose Spring Period, as does an increased social complexity due to larger populations and extensive long distance trade contacts. Specific projectile point types associated with this period are the Rose Spring and Eastgate; research attests to the existence of several semi-permanent villages that made use of multiple ecological zones, as well as the establishment of extensive trade routes throughout Southern California. The final prehistoric period here mentioned is the Late Prehistoric Period; key indicators associated with this period include a broad diffusion of pottery west from the Colorado River area, an abundance of coastal shell beads, and two particular projectile points (Desert Side-notched and the Cottonwood). With the presence of well-established trade, complex socioeconomic and sociopolitical organization developed and by approximately 1,000 to 500 years before the present, social complexity had likely reached the chiefdom level. An increase in population resulted in the gradual intensification of much broader environments and food resources. By the mid 17th Century, occupation levels decreased in the Antelope Valley, effectively marginalizing the area as one of limited socio-cultural complexity. Most researchers consider the Late Prehistoric Period an extension of the ethnographic present, a claim that is supported by both recorded oral traditions as well as the archaeological record. Ethnographic Background The project area is located in the western portion of the Antelope Valley, a region in which the prehistoric cultural history is poorly documented and/or understood (Kroeber, 1925; Moratto, 1984; Sutton, 1996). Two primary ethnographic populations are known to have inhabited regions that are transected by the current project APE, the Tataviam and the Kitanemuk. Various Native American culture groups such as the Chumash, the Serrano/Vanyume, and the Tongva, are also known from areas surrounding the Antelope Valley. It is also noted by Sutton (1988; 1996) that existing archaeological evidence attests to regional trade actively occurred between local population groups and other Western Mojave culture groups (e.g. Mojave or the Chemehuevi), indicating that these desert groups may also have utilized or otherwise traveled through the Antelope Valley region. Geographically, the Tataviam occupied territory in the southern Antelope Valley, while the Kitanemuk occupied land to the north of the Tataviam, principally in the region around, and farther north of, the Tehachapi Mountains. During the period of European contact Tataviam territory may have ranged east of Piru, through the entire upper Santa Clara River region, northwards to Pastoria Creek and east to Mount Gleason (King and Blackburn, 1978). Likewise, the Kitanemuk territorial sphere covered the western Antelope Valley, which they may have contentiously shared with their southerly neighbors the Tataviam, north to include the Tehachapi Mountains and the eastern High Sierras. Kroeber (1925) and others recognize the Tataviam as part of the Fernandeño group, a generalization referring to all Native populations that were eventually assimilated by the San Fernando Mission. The subsistence strategy of the Tataviam was that of a complex hunter-gatherer society living in small villages and satellite camps that were established near reliable water sources such as streams or rivers sourcing from the local mountains and foothills or shoreline settlements around established lakes within the flat desert valley. At a more recent period, it is believed that a chiefdom-type societal structure was adopted, with a single chief overseeing the people inhabiting villages. Plant and animal varieties of particular importance for Tataviam subsistence include, but are not limited to, acorns, seeds, berries, yucca, cactus, and game such as deer and rabbit. Specific knowledge of cultural traits of the Tataviam is scarce, as little culturally significant information regarding traditions such as religious believes, oral histories, or folklore have been lost as a result of the forced subjugation of this population by European occupation and Missionization. Material culture types associated with the Tataviam are similar to those of their neighbors and include elaborate basketry, ornamental and functional items crafted from shell, steatite, stone and bone. The Kitanemuk are associated with the Serrano division of the Shoshonean group and as is the case with their neighbors the Tataviam, little archaeological or ethnographic data exists that details this obscure population (Blackburn and Bean, 1978; Kroeber, 1925). Blackburn and Bean (1978) described the Kitanemuk as mountain people who occasionally ventured to the lower desert valleys during cooler seasons. Similarly to the Tataviam, the Kitanemuk most likely practiced a seasonal hunter-gatherer subsistence strategy dictated by the seasons. Primary camps and villages were mostly situated in the Tehachapi Mountains and foothills, as well as farther to the north. Important plant and animal varieties include the acorn, pinon pine nuts, native tobacco, yucca, as well as the hunting of small and large game. Material culture types associated with the Kitanemuk are similar to those of the Tataviam, including the manufacture of lithic projectile points and tools, wooden vessels with shell inlay, as well as advanced basketry. It is noted that the Kitanemuk, unlike their surrounding neighbors' preference for cremation, appeared to have buried their dead (Kroeber, 1925). Historical Background Antelope Valley Historical Overview Historic cultural resources are generally more than 45 years of age and range from the earliest time of contact with Europeans to around the year 1960. Numerous types of historical cultural resources can include trails and highways, homesteads and other structures or buildings, remnants of single or time based use activities such as trash deposits, and historically documented landscape sites such as the camp sites of Spanish explorers. Any cultural resource that may be evaluated as significant, important, or unique under current cultural resource protection laws and that can date to more than 45 years of age is considered to be an historic cultural resource. The historical setting for the current APE can be divided into three parts: The Spanish Period (ca. 1533 to 1821), the Mexican Period (1821 to 1848), and the American Period (1848 to Present). The Spanish were the first known Europeans to explore and colonize the land area of what is known today as California, territory known to them as Alta California (area known as the present-day State of California, U.S.A.) and Baja California (presently known as the Mexican states of Baja California Norte and Baja California Sur). This period of Spanish exploration of eventual colonization is now known as the Spanish Period. Early reconnaissance of California began in 1540 with Hernando de Alarcon's ocean expedition traveling northward up the Gulf of California and into the mouth of the Colorado River, thus making those travelers the first Europeans to enter California. From 1542 to 1543, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo led an ocean expedition to explore the coastal perimeter of California (Laylander, 2000). Cabrillo and his crew first stepped ashore at the present day harbor of San Diego, claiming California for the King of Spain. In addition, the expedition visited most of the Channel Islands and the land near the City of Ventura, and sailed as far north as Monterey Bay, maybe as far north as Point Reyes while failing to site San Francisco Bay. By the 1560s established sea-trade routes controlled by the Spanish ferried goods from Asian commercial outposts to territories in present-day Mexico by way of the California Coast. The long and arduous trip resulted in many galleons stopping along the coast looking for food and water, thus bringing Europeans into contact with the local Native Californians. With this elevated traffic of goods across the Pacific, raids against Spanish galleons, particularly by Sir Francis Drake, motivated the Spanish to better map California with the intent of establishing ports along its coastline to protect and refurbish the Manila galleons. It took several years after these early explorations of California before official Spanish colonization occurred. In 1769 Franciscan administrator Junípero Serra and the Spanish military under the command of Gaspar de Portolá arrived in San Diego. Thus began the eventual establishment of twenty-one California Missions and Spanish Missionization efforts, the purpose of which was to "convert" the Native Californians to Catholicism within a ten year period and then return the Mission lands to the Indians. The first documented Europeans in the Antelope Valley were the Spanish explorers Captain Pedro Fages in 1772 and Father Francisco Garcés in the late 1770's. At this time, the Tataviam and Kitanemuk culture and life ways were being heavily disrupted as the process of Spanish Missionization had commenced. The founding of the San Fernando Mission in 1797 instituted a direct impact on the region's native inhabitants. Within a few generations, most of the knowledge regarding the language and culture of these local groups had vanished. At the time of the Spanish arrival, population estimates of California Indians are placed at about 310,000 individuals. By the end of the Spanish reign, through unhygienic Spanish population centers (essential labor camps), European disease, incarceration of Indians, excessive manual labor demands and poor nutrition, the population declined as a result of over 100,000 fatalities, nearly 1/3 of the California Indians (Castillo, 1998). Between the first founding of the Spanish Mission, increased migration and settlement occurred in the territories of Alta California until unrest among these new residents impacted Spanish control of the area. The Mexican Period is marked as beginning in 1821 and is synonymous with Mexico's independence from Spain. Mexico becomes California's new ruling government and at first, little changed for the California Indians. The Franciscan missions continued to enjoy the free unpaid labor the natives provided, despite the Mexican Republic's 1924 Constitution that declared the Indians to be Mexican citizens. This monopoly of Indian labor by a system which accounted for nearly 1/6 of the land in the state angered the newly land-granted colonial citizens. This led to an uprising of the Indian population against the Mexican government and the eventual secularization and collapse of the mission system by 1834. After the fall of the missions, return of the land to the California Indians was mandated by the government, though little land was. Other European countries increased their presence in California during the Mexican Period, among them the Russians and the Americans. American ships from Boston traded with the towns and Missions mostly for tallow and hides. In addition, trappers and hunters begin to operate in the state entering by land from the east. William Manley and John Rogers, American explorers, were among the first non-Native Americans to traverse the antelope Valley in 1850. Prior to Manley and Roger's arrival in the Antelope Valley came Jedidiah Smith, Kit Carson, Ewing Young, among others, who entered the area in the late 1820s and 1830s. During the Mexican Period, occupation of the Antelope Valley was virtually non-existent. Occasionally, hunting parties concerned with the rounding up of runaway Indians ventured into the valley and the surrounding areas. At this time, it is estimated that very few California Indians peopled the Antelope Valley on a regular basis. In 1846, armed conflict erupted between Mexico and American forces, resulting in the increased presence of American military forces within California. Rapidly, Mexican resistance deteriorated and the United States occupied Mexico City in 1848, marking the beginning of the American Period. California becomes a U.S. holding with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February 1848, thereby ending the Mexican-American War and ceding much of the southwest territories to the United States. Just prior to the signing of the Treaty, gold was discovered along the American River near Sacramento, sparking the major influx of American adventurers into California. In 1850, California was formally admitted into the Union as the 31st state. At the beginning of the American Period, little notice was paid to colonizing the Antelope Valley. In fact, most of the late 19th Century can be described as a time when people were mostly passing through to other destinations. However, sparsely dispersed ranches were established in the Antelope Valley during the 1860s. The Homestead Act of 1862 and the Desert Land Act of 1877 greatly contributed to the settlement of the Antelope Valley. The Homestead Act opened up public lands to citizens for settlement, based on very minimal requirements. The Desert Land Act intended to "encourage and promote the economic development of arid and semi-arid public lands of the western United States. Through this Act, individuals may apply for a desert-land entry to reclaim, irrigate, and cultivate arid and semi-arid public lands." Agriculture, gas and mining endeavors, and settlement stimulus endeavors such as the Homestead Act and the Desert Land Act contributed to the increased population of the Antelope Valley during the later stages of the 1800s. It was also during the late 1800s that established transportation routes were formed between Los Angeles and the Antelope Valley, including the Butterfield Stage Overland Mail route (1858), the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad, Southern Pacific Railroad (1876), Antelope Valley Line, Union Pacific Lone Pine Branch, the Santa Fe Railroad Branch, among many others. The early 1900s was a period of innovation, which included mechanical irrigation and electricity. Also during this period, an avid pursuit of alfalfa cultivation occurred, quickly elevating this as the Antelope Valley's major crop. Lancaster The city of Lancaster was settled by an influx of people associated with the railroad, mining, oil prospecting, and agriculture. Mr. B.F. Morris purchased 6,000 acres of land in and around what would become Lancaster from the Southern Pacific Railroad, including ground that had previously been laid out as the townsite by M. L. Wicks. The construction of railroad related maintenance buildings and staff housing, as well as the increased interest in agriculture and mining activities contributed to the firm establishment of Lancaster as an Antelope Valley city, status that has been re-affirmed in modern times thanks to the establishment of the Muroc Army Airfield (later, Edwards Air force base) and other aerospace industry related endeavors. Rosamond and the Tropico Gold Mine The city of Rosamond was another depot on the Southern Pacific Rail Line in 1876 and a trading post for local mines. First known as Bayle Station or Baylesville after postmaster David Bayles (1885), the town was later renamed Rosamond (Rosamond County Library vertical file, n.d.). Rosamond town site lots were obtained from the Southern Pacific by an E.H. Seymour in 1904 and sold to a C.C. Calking three years later (Settle, 1967), who then "sold the mortgage to Charles M. Stinson, who in turn presented [deeded] it to the Union Rescue Mission of Los Angeles who foreclosed the mortgage in 1916. In 1935, the Rescue Mission began selling lots in the townsite, later presenting the remaining property to the community" (Darling, 2003). Prior to the settling and eventual development of Rosamond, Tropico Hill was being mined for clay by Dr. L.A. Crandall who purchased the mine in 1882. Hamilton renamed the mine "Hamilton Hill" and during the course of the clay-mining activities, gold was discovered. Having changed names again, the then known "Lida Mine" was sold to the Antelope Mining Company in 1908 and again to the Tropico Mining and Milling Company in 1909. Eventually the mine was acquired by the Burton brothers in 1912, who were former employees of the Tropico Mining and Milling Company. For a brief period between 1942 and 1946, in support of World War II wartime mining efforts, the mine closed. Once the war was past, the mine reopened and remained in operation until 1956. The Tropic Gold Mine was "one of the most successful gold mines in California" (Cunkelman, 2001). Palmdale & Pearland Initially settled by German-Swiss immigrants from the Midwest in 1884, "Palmenthal" prospered as a fruit and grain agricultural operation until the drought of the 1890s. A second settlement known as Harold or Alpine Station followed, located at the intersection of the Southern Pacific Rail Line and modern day Barrel Springs Road. Each of these settlements failed as a result of the Southern Pacific moving its booster engine station farther north. The name officially became Palmdale in 1890, during a time of immense growth and prosperity. The construction and completion of the "Palmdale Ditch" between 1918 and 1919 brought residents of Palmdale a reliable source of fresh water, stretching between the Little Rock Dam and the Palmdale Reservoir. Located southwest of Palmdale, Pearland is a short-lived community that has since been incorporated as part of on-going development. As its namesake, Pearland was never officially recognized as an autonomous town, but rather "a crossroads in a community dominated by pear orchards" consisting of but a few buildings at the intersection of Avenue S and 47th Street. The pears eventually died off and were replaced by peaches, though the name remained. California Aqueduct One of the most notable technological developments of early 20th Century California history was the construction of the California Aqueduct. Completed in 1913, the aqueduct connects the Owens Valley water source with the population of Los Angeles by means of surface and subsurface canals bisecting the Antelope Valley. Earmarked and funded in large part by Los Angeles residents in 1904, "the project revived the economy of Antelope Valley communities Lancaster, Mojave, Fairmont, and Elizabeth Lake whose farms and business had been decimated by a decade-long drought beginning in 1894." Paleontological Resources Paleontology is a branch of geology that studies the life forms of the past, especially prehistoric life forms, through the study of plant and animal fossils. Paleontological resources represent a limited, non-renewable, and impact-sensitive scientific and educational resource. As defined in this section, paleontological resources are the fossilized remains or traces of multi-cellular invertebrate and vertebrate animals and multi-cellular plants, including their imprints from a previous geologic period. Fossil remains such as bones, teeth, shells, and leaves are found in the geologic deposits (rock formations) where they were originally buried. Paleontological resources include not only the actual fossil remains, but also the collecting localities, and the geologic formations containing those localities. Methods Archival — Archaeological and Paleontologic Research ArchaeoPaleo Resource Management, Inc. conducted a records search for the Los Angeles portion of the project area at the South Central Coastal Information Center at California State University, Fullerton and at the San Joaquin Valley Information Center located at California State University in Bakersfield for the Kern County portion. These locations are divisions of the California Historic Resources Information System (CHRIS) and are the local legal repositories for the State's archaeological archives. Included in this research effort was a search of historical publications for additional cultural resources near the project area, including the California State Historic Resources Inventory, the National Registry of Historic Places, California Historical Landmarks (1990), and California Points of Historical Interest (1992). A Vertebrate Paleontology Records Check was conducted at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County by Samuel A. McLeod, Ph.D. APRMI provided Dr. McLeod with the appropriate 7.5 minute Topographic maps outlining the proposed backbone line and projected reservoir and pump station locations. The maps provided were the Soledad Mountain, Little Buttes, Rosamond, Lancaster West, Lancaster East, Ritter Ridge, Palmdale, and Little Rock USGS topographic quadrangles. Archival research was also completed by Robin D. Turner at the Buena Vista Museum in Bakersfield. Survey Methodology Shannon Loftus, MA/RPA and Robin Turner, MA/RPA of APRMI conducted an intensive archaeological and paleontologic pedestrian survey of the project corridor, including the backbone line, four proposed reservoir locations, two distribution pump stations, and two booster pump stations between January 26, 2008 and February 5, 2008. Survey methodology consisted of pedestrian survey using 10-15 meter transects in a linear fashion when in portions where one archaeologist covered the ground and 15-30 meter transects walking in tandem. Strategic survey methods were employed in areas of steep terrain; all finger mesas and ridges were investigated, as were slopes deemed reasonable or likely to possess cultural materials. Methodology specific to each parcel is discussed below in the Survey Results section. The backbone portion of the project is planned within the roadbed, thus windshield surveys were primarily employed in residential, commercial and industrial areas. Pedestrian surveys were employed for all dirt roads and trails. Artifacts and sites identified during the reconnaissance were geographically recorded with a Garmin® Etrex Legend Global Positioning System (GPS) Receiver. Notation was made of all artifacts and sites, and photographs of unique isolates and sites were taken. In addition, photographs of the backbone and the eight parcels were taken to illustrate the various environmental settings and built environment and are included in the survey results section of the original Loftus and Turner archaeological report (2008). One proposed parcel was entirely inaccessible (Distribution Pump Station 2), and one was partially inaccessible (Reservoir 3). These instances of no-access are further discussed in the survey results section. Proposed Distribution Pump Station 2 (40th Street East and Avenue P), adjacent to the Palmdale WRP, was not accessible due to fencing and signage indicating "No Trespassing" and "Airport Property." Attempts to locate personnel at the Palmdale WRP for access were unsuccessful. The property was visually inspected from the public side of the fence and a portion of a historic period homesite was evident. The homesite proper is excluded from the parcel, but contributing elements such as ornamental trees and a small orchard are visible. Should this parcel be selected, access will be required for comprehensive inventory of the property. The eastern portion of the proposed parcel for Reservoir 1 (south face of Quartz Hill) was also inaccessible as it was fenced. No signage was visible, and attempts to contact personnel for access were unsuccessful. This portion of the parcel was visually inspected from the public side of the fence and appears highly disturbed. Mechanical push-and-redeposit activities have leveled portions of the land within the fence, as well as created large earthen berms and boulder piles along the interior of the fence. Should this parcel be selected, access will be required for comprehensive inventory of the property. Since the pedestrian survey was completed, the locations of the following project components have been refined:, (1) the location of Booster Pump Station 1 has been changed to the proposed location indicated in Figure 2-1; (2) a pipeline has been added along Avenue M to connect Booster Pump Station 1 to the backbone pipeline along Sierra Highway; (3) the location of Reservoir 4 has been refined; (4) the overland pipeline leading to Reservoir 4 from Mojave Tropico Road has been realigned; (5) an alternative Distribution Pump Station 1A has been added at the LWRP; and (6) a pipeline connecting the LWRP to Distribution Pump Station 1 has been added. Additional reconnaissance surveys and record searches for cultural resources would be required prior to implementation of these project components.

|

Bowers Cave Specimens (Mult.)

Bowers on Bowers Cave 1885

Stephen Bowers Bio

Bowers Cave: Perforated Stones (Henshaw 1887)

Bowers Cave: Van Valkenburgh 1952

• Bowers Cave Inventory (Elsasser & Heizer 1963)

Tony Newhall 1984

• Chiquita Landfill Expansion DEIR 2014: Bowers Cave Discussion

Vasquez Rock Art x8

Ethnobotany of Vasquez, Placerita (Brewer 2014)

Bowl x5

Basketry Fragment

Blum Ranch (Mult.)

Little Rock Creek

Grinding Stone, Chaguayanga

Fish Canyon Bedrock Mortars & Cupules x3

2 Steatite Bowls, Hydraulic Research 1968

Steatite Cup, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x5

Ceremonial Bar, 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig x4

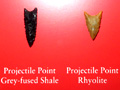

Projectile Points (4), 1970 Elderberry Canyon Dig

Paradise Ranch Earth Oven

Twined Water Bottle x14

Twined Basketry Fragment

Grinding Stones, Camulos

Arrow Straightener

Pestle

Basketry x2

Coiled Basket 1875

Riverpark, aka River Village (Mult.)

Riverpark Artifact Conveyance

Tesoro (San Francisquito) Bedrock Mortar

Mojave Desert: Burham Canyon Pictographs

Leona Valley Site (Disturbed 2001)

2 Baskets

So. Cal. Basket

Biface, Haskell Canyon

2 Mortars, 2 Pestles, Bouquet Canyon

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.