|

|

By JO ELLEN RISMANCHI. | SCVHistory.com 1998.

|

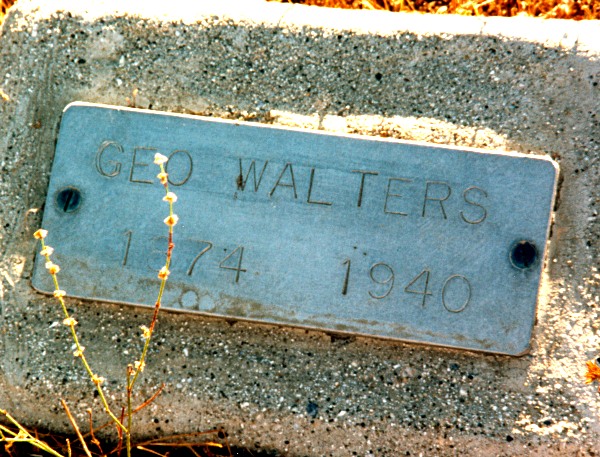

Tucked away in an all-but-forgotten Canyon Country knoll, in one of the last remaining vestiges of the once enormous Mitchell ranch, lie the cracked, weed-strewn headstones of a small family cemetery. There, amid a large, overgrown, solemn juniper tree that presides over dry sage, the family, friends and neighbors of Thomas Findley Mitchell rest. Among them is George Walters. "He was homeless and Dad just brought him home one day to live with us. ... Dad was always doing something like that," recalls 58-year-old George Dyer. George Walters lived with the Dyers in the mid-1930s, some years before George Dyer was born. But because of those family stories, the latter is able to pass along the memories that still remain of Walters. On a hot July 4 afternoon in 1998, the children of Willis and Dorothy Smith Dyer fondly remembered George Walters during the Mitchell family reunion held at Heritage Junction Historic Park. Letty Foote, George Dyer's sister, reminisced with her brother and others present about what a special man Walters was to the Dyer family. In George Dyer's words, Walters was an endearing, homeless old man who was brought to their doorstep after becoming estranged from his immediate family. If Walters was not a tall man, his size was no measure of his stature, Foote said. "He was so special that Dad and Mom named George (the youngest son of three children) after him," she said. George and Letty's parents married in 1933. Foote said Walters came to live with the Dyer family sometime in 1935. At the time, America, and the Dyers, were suffering the depths of the Great Depression. "No one had any money back then," George Dyer said. "People were just scraping to get by, trading goods for services and services for goods. They would go hunting for a week and come back with a bobcat. Then they would take the live cat in a cage to old Chinatown and sell the entire thing for $25. During the days of the depression, $25 was a lot of money." The payment for that bobcat might have been the equivalent of nearly half a month's salary for the average worker. Chinatown in 1930s Los Angeles did not resemble the Chinatown of today. Old Chinatown, located then where Union Station sits today, was a foreign place of great mystery with winding, narrow alleys, herb shops, open air markets, music, lots of animated, loud conversations in many different Chinese dialects and, hidden from view, smoke-filled opium dens. Beneath the crowded structures and narrow streets were underground tunnels and passages unknown to outsiders until Union Station's construction. In those pre-freeway days, when people traveled to Los Angeles they spent the night, allowing for the condition of the roads and the seemingly great distance of 40 miles from the Newhall-Saugus area to "the City." The Santa Clarita Valley consisted of several separate communities, railroad stations, post offices and general stores — Acton, Agua Dulce, Lang, Kent, Thompson, Soledad, Solemint, Mint Canyon, Humphreys, Honby, Ravenna, Saugus and Newhall. The landscape was pastoral, covered by expansive, green vineyards, cattle ranches, pig and turkey farms. The Santa Clara River was a wide, active, uncontained, free-flowing natural river, with these communities and the railroad having established themselves along the riverbank. At the beginning of a hot summer day, the air at the Mitchell homestead would be alive with the scent of plantings such as apricot, peach, pear, plum, almond and fig trees; wheat and alfalfa from the fields; and, closer to the house, roses and ripening grapes, gooseberrys and currants. Foote recalls that her family was like many others of that tough era. They survived the depression because of the benefits of the Works Progress Administration, an alphabet-soup program that found jobs for workers so they could earn a wage — not a large wage, but sufficient to give workers dignity and funds just to get by. The program also provided food and clothing to workers' families. Dorothy Dyer recalls standing in a long line in San Fernando for food and some clothing for her family. Walters served as ranch caretaker when the family went hunting or was away on trips to downtown Los Angeles. According to George Dyer, as told to him by his father Willis, Walters migrated to Los Angeles, leaving behind the live he had known. It was the story of many men in the 1930s. But Willis Dyer was so impressed with the homeless, unemployed Walters that he brought him home to the family's five-acre Vasquez ranch. Exactly what so impressed the elder Dyer will never be completely known. But the children of Dyer think they know. To their knowledge, Walters was the kindest, nicest person anyone could ever meet. When Willis Dyer went to work for the county Road Department at 25 cents an hour, Walters helped run the ranch, including caring for the animals, carpentry, farming and babysitting. Willis Dyer even helped Walters build his own separate living quarters on the Dyer ranch. "He (Walters) was a very good carpenter and handyman," said Foote. In finding a home and a job, Walters recaptured his dignity, and Walters and the Dyer family found mutual love and respect. Walters so bonded with the family that when he died in 1940 at age 64, he was interred in the Mitchell-Dyer family cemetery. "He was a gentle, kind person, like a grandfather," said Foote. "He helped babysit me and my brothers on the five-acre Vasquez ranch." Foote's mother Dorothy recalls a slightly different version of how Walters came to live with the Dyers. She remembers meeting the soft-brown-eyed Walters in Newhall. He was old, homeless and sick with a heart ailment. During the depression when America didn't have the institutional social welfare that exists today, people took it upon themselves to do what they could not just for their own families but for those around them in the community. People who were down on their luck were not known as they are day — as a collective mass called the "homeless." When folks encountered such a person they saw a person, not a label — someone with potential, not someone who struck fear in strangers' hearts. Dorothy Dyer brought Walters to the Vasquez ranch to live and work. He was loved, much as an adopted grandfather might be, by the entire family. Foote stands by her mother's version because, she said, this would account for why she remembers him so well. Foote remembers that Walters died before George Dyer was two years old and her family had moved to the "honey house." Once known as Dyer's Honey House, today it is Warmuth's Honey House, standing where it has always been on Sierra Highway in Mint Canyon. When Walters died in 1940 the hearse that carried him parked at the bottom of the knoll. Willis and Frank Dyer carted his heavy casket up the long, winding hill to the cemetery at the top. Walters so endeared himself to the family that he was laid to rest with all the respect due a beloved grandparent or other kin. While it is not known with certainty, Tommy, Albert and Wesley Mitchell may also have served as Walters' pallbearers, Foote said. Foote recently traveled to Des Moines, Iowa to visit her mother. She hoped to return with a photograph of Walters. None was located; the only extant picture of Walters is the one in the minds of those who lived with him and loved him. The fact that Willis Dyer's memory and that of his widow differ doesn't seem to bother anyone. The truth is that because of one family's kindness and concern for its fellow man, such a bond was created that 58 years later, people still talk of George Walters. He was not known for any great education or wondrous accomplishment. In fact, nothing is known about his education. He is not listed in any encyclopedia, nor was he even remembered by the local paper when he died. Instead he is known today as a great man simply because of the Dyer clan and one woman with a vivid childhood memory. George Walters' story is one of empathy, triumph, love and success. He rests in the Mitchell-Dyer Cemetery. ©1998 Santa Clarita Valley History In Pictures |

Book by Richard F. Mitchell 2002

Cemetery ~1961

Adobe Home: Early Photos

1888 Mitchell House

R.F. Mitchell 1919-2002

Dyer Family, SCVTV 2009

Geo. Walters, 1874-1940

Archive Video 2008

Lost Cyn Bridge Widening 2012

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.

Who was George Walters?

Who was George Walters?