Image from the August 1893 edition of Good Roads magazine, which advocated for "the improvement of the public roads and streets" across the country and

shared best practices in road building. Click to enlarge.

|

The enactment of Senate Bill 805 by the California legislature on March 27, 1895, created a new state agency called the Bureau of Highways and for the first time clearly defined the state's interest in its public roads. Heretofore, most California roadbuilding had been undertaken by local governments or private parties, and the state government's highway development had been a haphazard and often slipshod affair. California's first legislature in 1851 had established the legal basis for public roads and had given the surveyor general the responsibility for making plans and suggestions for their construction. The lawmakers, however, had failed to provide that officer with either an adequate salary or a budget sufficient to carry out his duties. ...

Judicial hostility and the lack of legislative interest in highway projects resulted in practically no state work being done throughout most of the remainder of the 19th Century. Counties and private toll road operators, on the other hand, took an active role in road building, although the amount and quality of construction varied widely from county to county and region to region. Local politics and patronage, rather than skill and professionalism in route selection and construction, marked much of the work that was done. In short, as the 20th Century neared, California lacked anything approaching a cohesive highway system.

The nationwide bicycle craze of the 1890s, however, spurred Californians into re-examining their apathy toward highways. Well-off urban bicycle enthusiasts and their clubs, seeking places to ride outside the cities, began demanding improvements in the state's network of roadways. They balked at paying tolls for travel over private thoroughfares, and found most county and local roads outside the cities to be rutted, poorly drained bogs in winter and dust-choked bumpy tracks in summer. The cyclists soon allied with farmers, merchants and other shippers dissatisfied with rates and conditions set by California's railroads. They looked to a united network of passable roads to allow them to ship goods to market by wagon rather than by rail. At the same time, the railroads, secure in their dominance of California transportation, also promoted better roads to allow producers to get more goods to local freight stations. Similarly, steamship companies joined in seeking easier ways for passengers and cargo to reach wharves and terminals. Rounding out the campaign were humane societies, with the goal of alleviating hardships imposed on draft animals by inadequate dirt roads. Collectively, these interests comprised what came to be known as the "Good Roads Movement."

On a national level, Good Roads enthusiasts succeeded in prompting the federal government in 1893 to establish the Office of Road Inquiry (later the Bureau of Public Roads) to study ways in which public highways might be improved and to assist local and state movements. Events in Washington encouraged the cause in California. Good Roads promoters called statewide conventions in 1893 and 1894 to formulate policy and influence the legislature to increase government's role in bettering the state's highways. A third conference, held in Sacramento in February 1895, featured an appearance by General Roy Stone, head of the federal Office of Road Inquiry. In his keynote address, he urged Californians to keep up the pressure on their lawmakers and public officials to commit to a program of road improvement. The response was enthusiastic. Governor James Budd urged action, and the following month the legislature responded by creating the Bureau of Highways. The 1895 act provided for the appointment of three "competent persons" to compose the bureau during its two-year statutory life. The purpose of the new agency was investigatory and advisory. It was to hold public meetings in each county and collect information from the counties on local roads. The bureau was also to examine the geography and topography of the state, assessing the water supply and the availability of road-building materials, as well as preparing standard plans for bridges, culverts and other features that could be used by counties for their own road projects.

[Original caption]: The Bureau of Highways: R.C. Irvine in buckboard, J.L. Maude with camera, and Maje, Mr. Irvine's Irish setter. Picture taken in Riverside County in 1996.

(Click to enlarge.) Photo: California Department of Transportation.

|

Governor Budd's three appointed commissioners, Marsden Manson, Joseph Lees Maude and Richard Irvine, met in Sacramento on April 11, 1895, to organize the bureau. Manson was elected chairman and directed Maude to begin consultation with the governor and state prison directors for the operation of a rock-crushing plant at Folsom Prison. The plant, which had been authorized by the legislature that March, was to provide "metal" (pulverized stone) for use on local roads. ... Within a year, thoroughfares in Sacramento, Stockton, Marysville, Vallejo and other northern California towns were being covered with stone from Folsom. ...

Manson, Maude and Irvine also prepared for their survey of the state's roads. ... What the commissioners found throughout California was depressing, the result of "generations of neglect and apathy." The state's highway system, if it could be called such, had been developed during a period of "road decadence," when the best and brightest civil engineers went into the lucrative fields of mining or railroading, leaving highway work to less skilled practitioners. In many cases, counties adopted an unprofessional attitude toward their roads, allowing private landowners to encroach on rights-of-way and, in some cases, to change alignments altogether if it suited them...

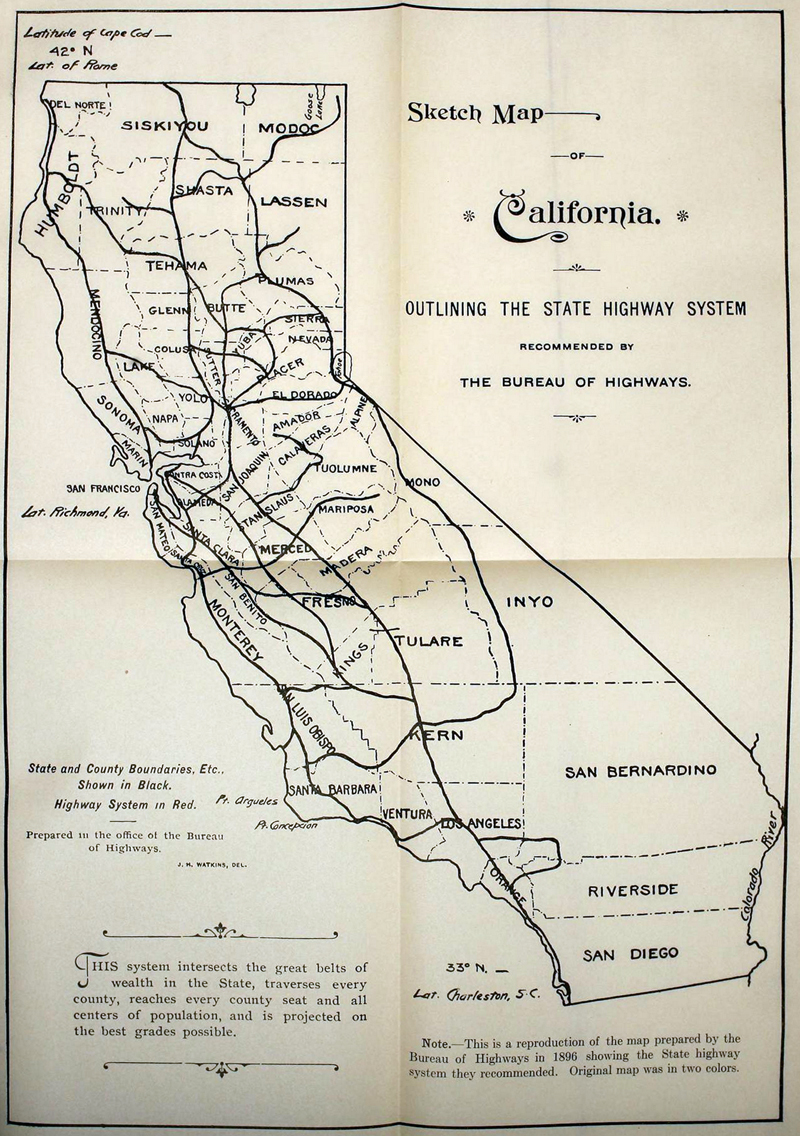

The commissioners estimated that ... $18,000,000 of public money had been squandered on practically worthless highway projects since 1885. ... The solution to this state of affairs was simple, but at the same time revolutionary: The state itself should construct and maintain a system of highways serving all of California. The state roadways proposed in 1896 by the bureau covered 4,500 miles, tapping timber, fruit, farming and mining regions, and connecting the principal population centers and county seats of each county. The routes selected stretched from Mexico (south of San Diego) to Oregon. ...

"Sketch map of California outlining the state highway system recommended by the Bureau of Highways." 1920 reproduction of 1896 map.

Click to enlarge. Photo: California Department of Transportation.

|

The financing of this ambitious network was to come from a tax of one quarter of one mill [a mill is 1/1000th of a dollar, i.e., one-tenth of a cent] on every dollar of assessed property in the state. This levy ... went before the legislature in 1897. What emerged from the capitol, however, proved both disheartening and harmful to the Good Roads cause. The legislature modified the bureau's recommendations so that almost any road, no matter how insignificant, could be classified as a state highway. In addition, the tax was there, but now most of the proceeds went directly to the counties, with little accountability. The legislature's proposals were so off the mark that they fell victim to the governor's veto. ...

Although the bureau went out of existence when its statutory authorization ended in 1897, the role of the state in highway matters had been firmly established. From then on, few questioned the legality, or even the propriety, of government planning and assisting road development. That same year, the legislature replaced the bureau with a Department of Highways. [It] continued the survey work begun by the bureau, but it too was unsuccessful in establishing a state highway system....

Full recognition of the state's role in highway development came in 1902 with the enactment of a constitutional amendment establishing the legislature's authority to create a highway system. Eight years later, voters narrowly passed an $18 million bond issue to construct just such a system. Engineers and planners began laying out this network, which would give Californians their first modern highways. The roads now had to be paved, with gentler grades and curves to meet the demands of an increasing number of automobiles and motor trucks. The routes they adopted for the new bond-issue highways closely paralleled those laid out by Manson, Maude and Irvine a decade and a half earlier, a testament to the foresight and hard work of the old Bureau of Highways.

[...]

Dr. Blaine P. Lamb is an archivist with the California State Archives in Sacramento.