Dedicated to the Women of California Who Have Helped More Than Any Other Agency in the Fight for Good Roads.

Author's Foreword.

The many inquiries which have come to the Good Roads Bureau of the California State Automobile Association during the past few years have served to emphasize the fact that there is a widespread and continuing demand for information as to California's state and county highways, while as a matter of fact no such publication has been extant.

The present volume has been prepared to meet that demand. It is in no sense a technical work, library shelves being full of such publications. Nor is it, even remotely, intended to be a touring guide, as road conditions change from day to day.

It is intended merely to tell what has been done in California as to the development of state and county highway systems, to picture how the present movement came into such a tremendous swing; and every attempt has been made to mention those men and women who took an active part.

The subject, naturally a dry one, has been treated in a more or less popular way. Yet the information put forth has been gathered from reliable sources and every attempt has been made to have it accurate. None the less it is entirely possible that inaccuracies have crept in, so comment and criticism are cordially invited in order that future editions may be free from any material fault.

Ben Blow.

San Francisco, December 1, 1919.

CHAPTER XXV: LOS ANGELES COUNTY

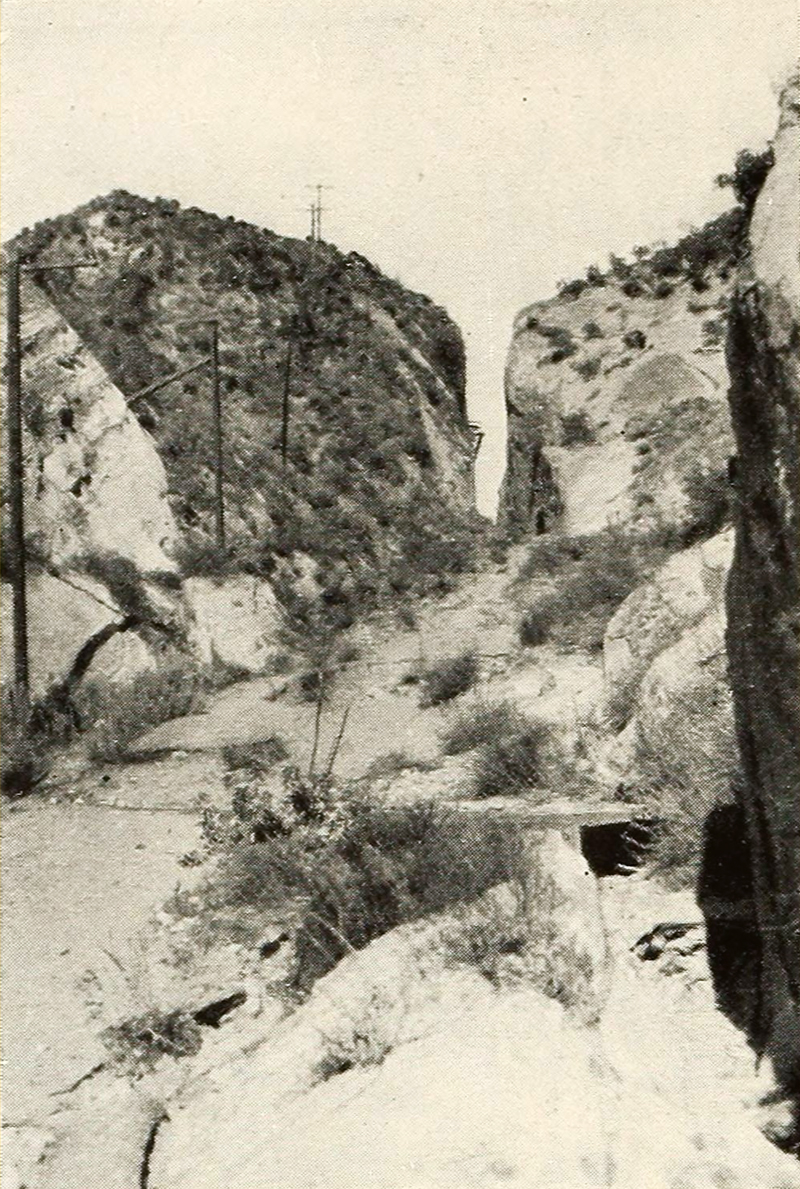

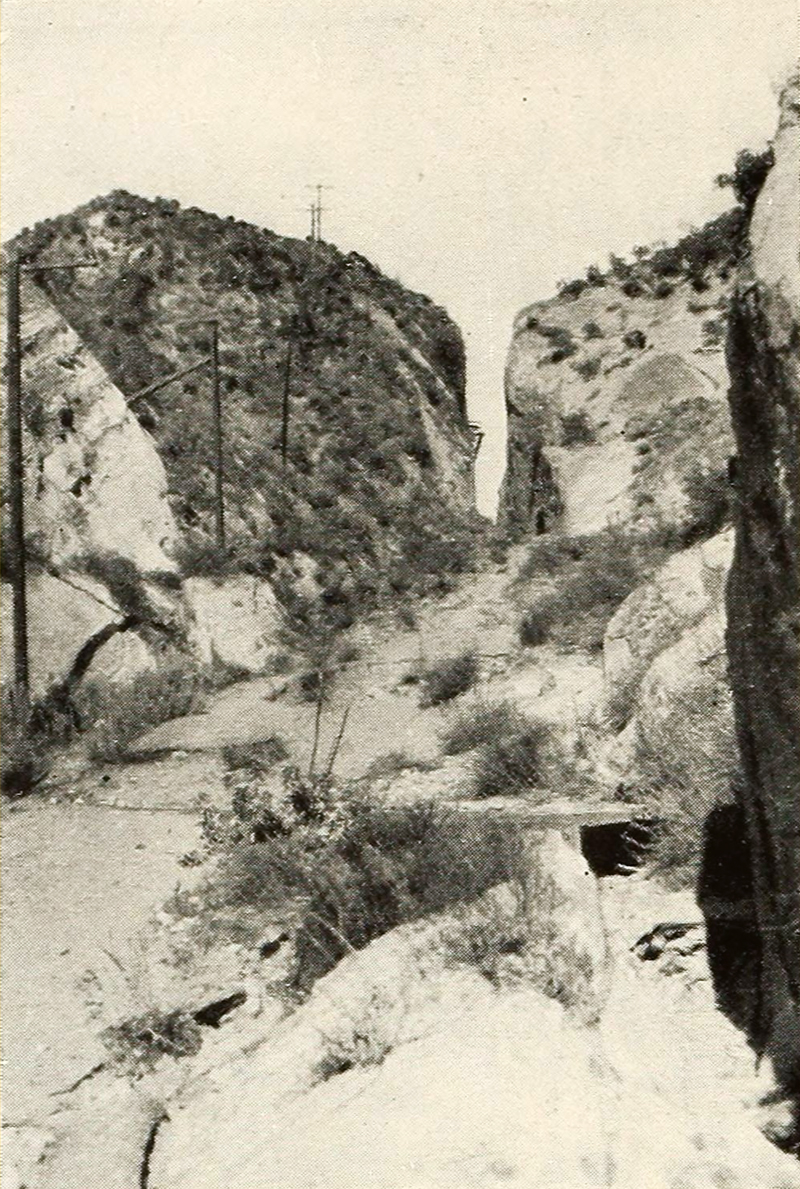

Beale's Cut (from book). Photo circa 1919. Click to enlarge.

|

Twenty-one years ago Los Angeles County began that road improvement which has become such a marked phase of its development, for in 1898 three hundred eighty-three miles of road were treated with oil, the oiling of earth roads at that time being regarded as about the last word in road improvement.

Since that time road building in this county has reached a development little short of marvelous, and in the latter part of 1919, 601.50 miles of well paved highway built to carry commercial traffic exist in Los Angeles County, while three thousand, three hundred fifty miles of oiled dirt roads, intended in the main to serve light touring traffic, have been developed and are being maintained.

In addition to these county roads the city of Los Angeles, comprising in its area 363.44 square miles, has 511.86 miles of paved streets and 724.43 miles of streets graded and oiled, many of these oiled streets being nothing more nor less than country roads twenty miles away from the business district, for so wide-spread in dimension is this amazing California city as to comprehend within its limits those road problems which are peculiar to county rather than city government.

Eliminating the paved streets as properly to be credited to city rather than county accomplishment, it may be said that the oiled streets, while not legally a part of the county road system, may well be considered as part thereof, giving an oiled-road mileage of 4074.43 and a total improved road mileage, taking in six hundred miles of paved roads, of 4674.43, which is little short of amazing.

In securing this great highway development Los Angeles County voted a road bond issue of $3,500,000 in 1909, being the second county in the state to undertake such an enterprise and put down, under that bond issue, three hundred seven miles of oil-bound macadam roads, the concrete road at that time being an unknown quantity in California, these oil macadam roads being twenty feet wide in the main and five inches thick.

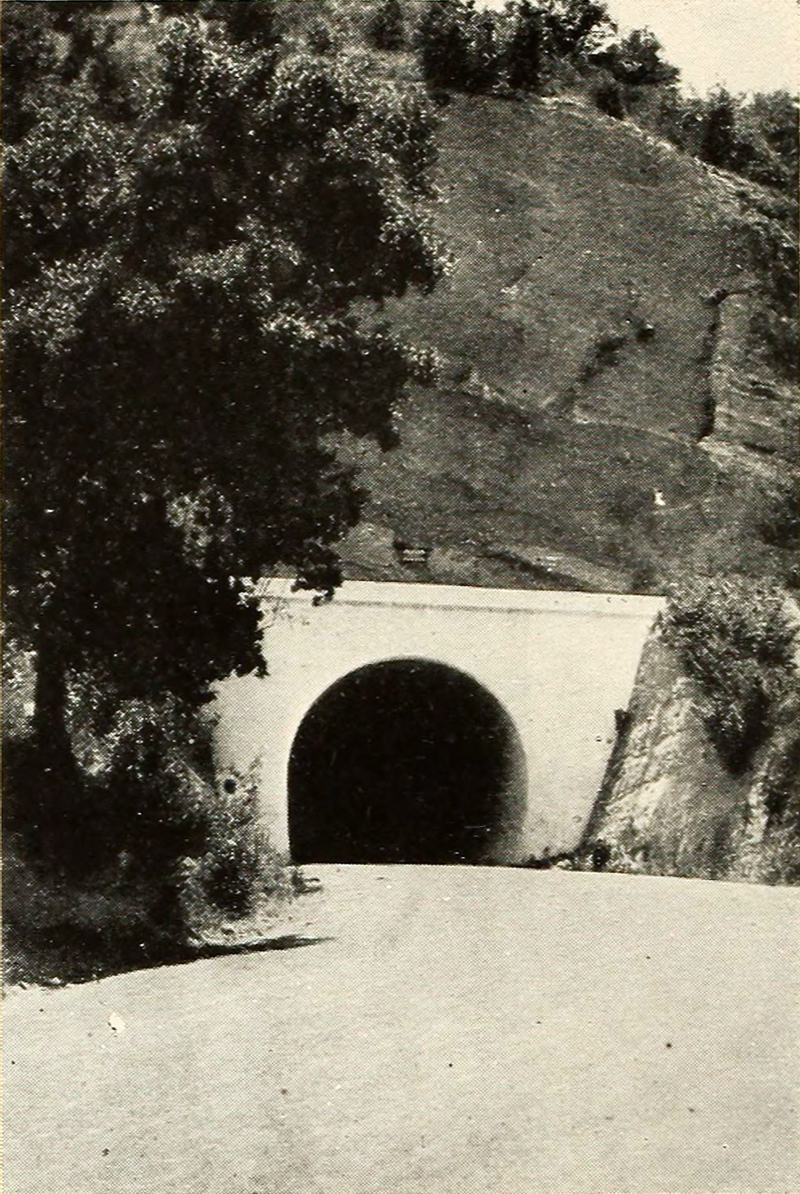

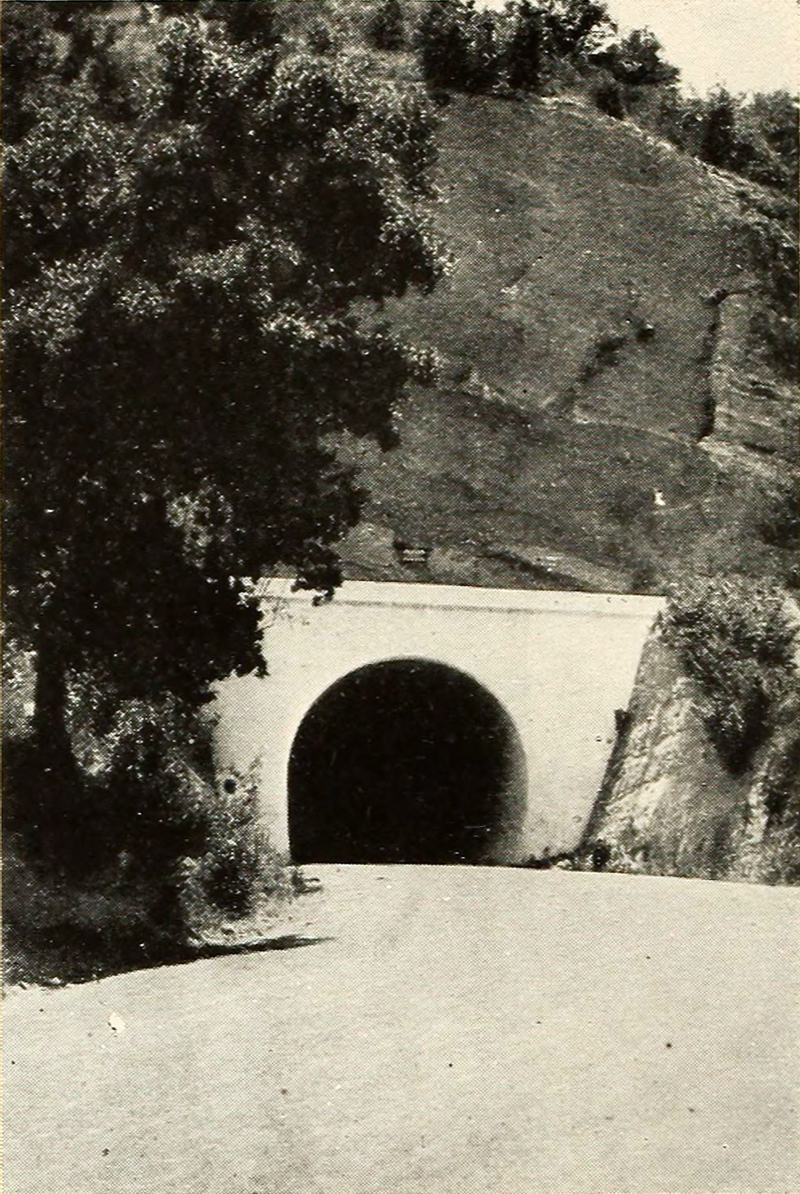

1910 Newhall Auto Tunnel (from book). Photo circa 1919. Click to enlarge.

|

Of the present system of paved roads five hundred twenty-three miles are of the type just mentioned, while seventy-eight and one-half miles are of the best type of concrete construction, twenty feet wide and five inches thick, surfaced with asphaltic oil and screenings to take up the wear and tear of heavy travel, the present tendency being to construct concrete highways wherever heavy traffic exists, a highway now contemplated for improvement by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, the Harbor Truck Boulevard, extending from the commercial center of Los Angeles to the harbor at San Pedro, setting a new standard for heavy-duty roads.

This highway, intended to carry an enormous tonnage, if expressed plans are carried out, to be forty feet wide, of a thickness of eight inches of concrete laid upon a well-rolled and compacted subgrade of disintegrated granite from six to eight inches thick, and covers a distance, outside of the city limits of Los Angeles and Vernon, of 13.32 miles. Inside the city limits of the places named about seven miles of pavement already exists, not of the type planned it is true, but none the less paved and required to be maintained no matter how huge the volume of traffic may become.

Other roads which, although serving a commercial traffic to some extent, bear that tremendous flood of automobile tourist traffic which centers around Los Angeles, are the Long Beach Boulevard and the Pico Boulevard, which reaches from the heart of the city of Los Angeles to Venice, Santa Monica, Ocean Park, and other beach resorts. Of the oil-bound macadam roads, intended in the main for pleasurable touring traffic, the Topango Canyon road perhaps stands foremost in scenic attraction, supplying as it does a link in a short tour originating in Los Angeles and thence, by way of Venice, Santa Monica, and Oceanside, leading up the coast past medieval-looking moving-picture establishments to where a rugged gash in the mountains opens Topango Canyon to the sea.

The Cahuenga Pass road also is attractive, although in different and less degree, and is much traveled both by pleasure and commercial traffic, as it supplies access to Los Angeles for the converged travel of both coast and valley routes of the State Highway.

In discussing the road-building accomplishments of a county such as Los Angeles in an article so limited in length as the present one only extraordinary undertakings are susceptible of mention, and of these perhaps the construction of the Newhall Tunnel is the most interesting. This tunnel, built by Los Angeles County, was presented to the State Highway, and through it pours that ever-increasing flood of travel which comes from the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys by way of the Tejon-Castaic Ridge State Highway route. Before the building of this tunnel and in the days when there was no State Highway Ridge route access into Southern California was had by way of Fremont Pass[1], a sheer cut eighty feet deep through conglomerate rock with grades of twenty-nine per cent, so narrow that only one vehicle could pass through at a time and so steep-sided that now and then a boulder dropped from the wall upon some unfortunate traveler. Access to Fremont Pass was had from the north by way of Antelope Valley and Boquet Canyon, and the pass takes its name because of the popular declaration that General John C. Fremont in his journeyings about California was responsible for its origin.

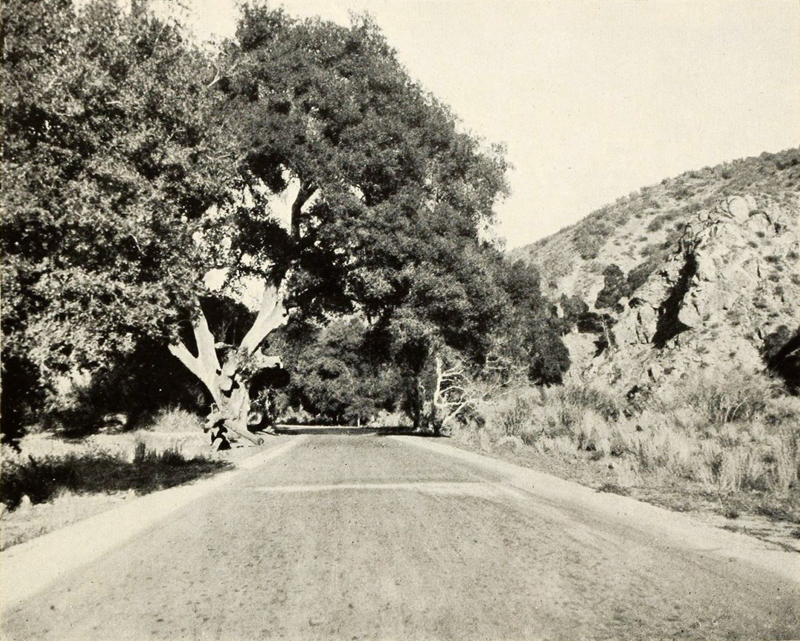

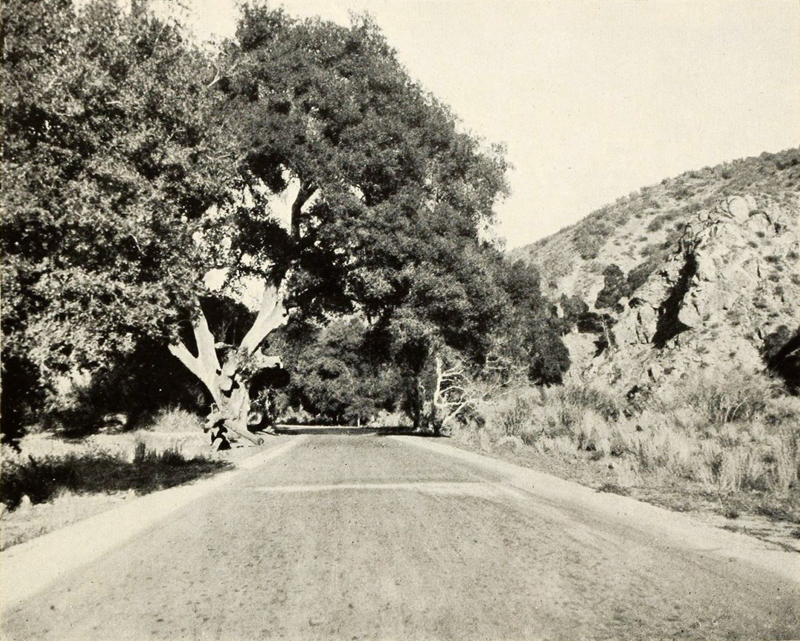

[Original caption:] Mint Canyon road paved by Los Angeles County and given to the state. (Photo circa 1919. Click to enlarge.)

|

In considering the road development in Los Angeles County it is only fair to say that the Automobile Club of Southern California has taken an outstanding part and in 1909, seizing upon the opportunity afforded by the adoption of a county charter, designated a committee to get the best road-building engineer who could be procured. This individual proved to be F. H. Joyner, at that time peaceably building roads in Massachusetts; and for ten years Mr. Joyner served faithfully and well, retiring to private life in the early summer of 1919, leaving behind him a host of friends and many creditable accomplishments.

Succeeding Mr. Joyner his principal assistant, George W. Jones, was named by the Board of Supervisors as County Road Commissioner, and this thoroughly competent road builder is now engaged in that further road development which is planned by the Board of Supervisors. This body, made up in 1919 of Jonathan S. Dodge, chairman; P.F. Cogswell, formerly State Senator; Jack Bean; F.E. Woodley; and R.F. McClellan, not only has taken part in past accomplishment but also is actively engaging itself for the future; and the activity of these men is largely responsible for the fact that under the 1919 State Highway bond issue the Lancaster-to-Bailey's road was taken over by the state, as well as the Oxnard-to-San Juan Capistrano road, the San Gabriel Canyon road and the Arroyo Seco road back of Mount Wilson — the taking over of these roads by the state alleviating the white man's burdens resting upon Los Angeles County in so far as roads are concerned to no inconsiderable extent.

In furtherance of its road-building undertakings Los Angeles County, maintaining a county forester, has advanced far in highway tree planting and beautification, while from a bridge standpoint it has developed some splendid structures, the Colorado Street bridge over the Arroyo Seco in Pasadena being easily first in magnitude, while over the same arroyo some distance below is the California Street bridge, a splendid span of reinforced concrete arches. In the same general location is the concrete-arch bridge over a tributary of the Arroyo Seco at Devil's Gate, a single span of sixty-four feet over a deep and rocky gorge, while over the San Gabriel River east of El Monte is a long plate-girder bridge with reinforced concrete floor, the general bridge scheme of the county matching well up with what in all probability is California's most highly developed county system of roads.

Webmaster's footnotes.

1. What is discussed here is Beale's Cut. It was commonly called Fremont Pass at the time this was written, but Fremont's troops actually passed over the ridge about a quarter-mile east of (the later) Beale's Cut. Fremont predated — and had nothing to do with — the cut.

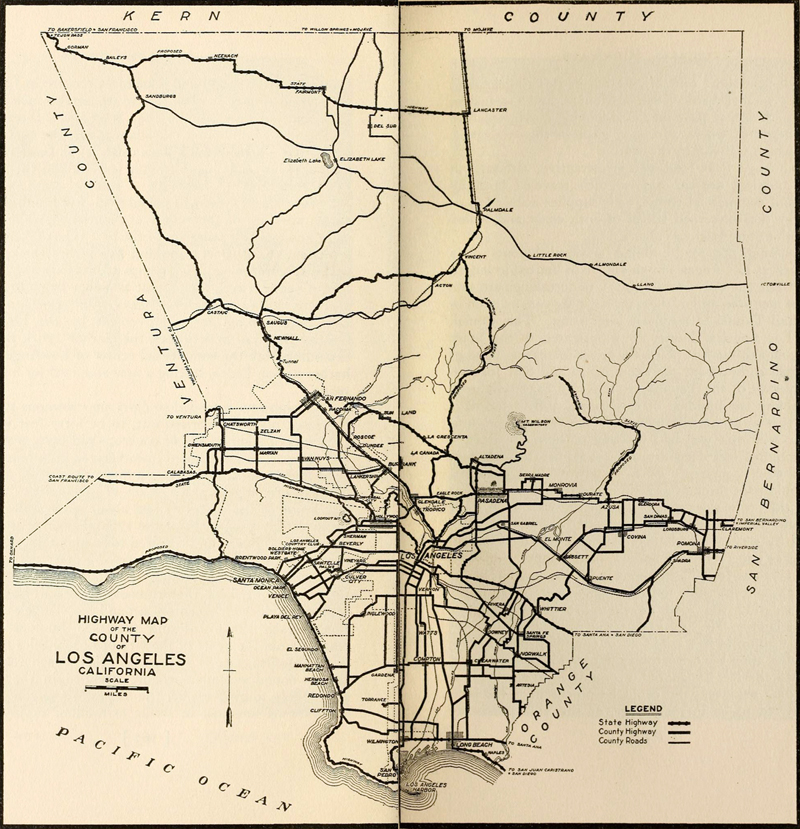

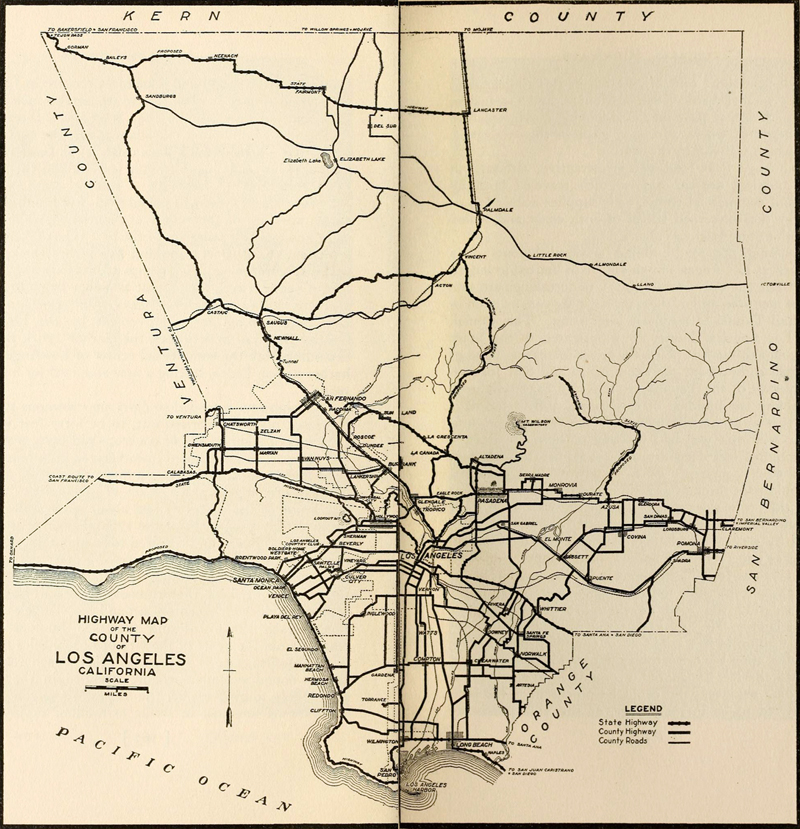

[Original caption:] Los Angeles County has the greatest paved road mileage of any County in California and is constantly adding to it.

More lines of the State Highway center in Los Angeles County than in any other County. (Click to enlarge.)